The Italian artist Marisa Merz spent many of her most creative moments in the kitchen of her Turin flat. She was happy working alongside her daughter, creating sculptures that, in time, as her obituary recorded, at first took up space above the cooker, but “eventually colonised the entire residence, creeping behind the television and over the dining table. The house was completely invaded.”

One of these, Untitled (Living Sculpture) – she never gave her works a title – is a looming presence, a mass of aluminium sheets twisted and stapled into tubes that hangs threateningly from the sky – or rather the ceiling of the Turner Contemporary in Margate, Kent – like some sort of alien creature.

This prodigious work is one of 80 by 50 female artists in Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950–1970, which runs until May 6. It is a celebration of the women who emerged after the second world war and who helped to “redress the gender imbalance” of the art world.

Timing was on their side. Postwar societies were changing, having been shaken and reshaped by the intense pressures exerted by conflict. In the new cultural landscape that emerged, the aspirations and frustrations of women were articulated by forceful writers such as Simone de Beauvoir, whose book The Second Sex helped to unleash a wave of feminist thought, which was further energised by Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics and Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch.

Superficially, Merz (1926–2019) typifies the secondary status of female artists of the day. She was happy to work from home, caring for her child, eschewing publicity, and apparently relaxed at being denied the recognition she deserved for her radical work in the Italian arte povera (“poor art”) movement of the late 60s. On at least one occasion her name was left off the roll-call of contributors at an exhibition. Her husband’s remained.

The show’s organisers are eager to emphasise that it is not intended to be a paean to feminism per se. The artists are not here for the arguments their work might make about women’s rights, or for any advocacy of (tedious) identity politics. No “gendered stereotypes”, to quote the Turner’s guest curator, Dr Flavia Frigeri. They are here because of their talent.

Frigeri quotes US writer Siri Hustvedt who wrote, somewhat cryptically, that “a work of art has no sex. The sex of the artists does not determine a work’s gender…” and in the show’s catalogue she acknowledges: “The peril there was, and continues to be, the association of artists on the basis of gender alone without recognising the cultural, ethnic and geopolitical circumstances that shaped individual practices.”

So what do we find? This is a complex show with some familiar names – Elisabeth Frink, Barbara Hepworth, Louise Bourgeois, Agnes Martin – but it is made trickier to circumnavigate by a perversely compiled catalogue. The curator’s introductory notes are in the middle and the artists’ biographies and their works separated arbitrarily on either side of it. They are given in no particular order. Furthermore, the signage adds to the challenge, fashionably but annoyingly presented, with labels on the floor or yards from the work they refer to.

The exhibition is divided into five sections. The first, labelled “Beyond Form”, opens with a powerful painting by Howardena Pindell: dense layers of painted dots in a swirl of subdued reds and blues. Pindell, 80, who resigned from Moma in 1979 in protest at racism in the art world, is perhaps best known for her searing videos that exposed race discrimination and police brutality. Here, the tiny dots in the painting represent the red circles used to mark drinking glasses to be used only by people of colour.

The Polish artist Maria Teresa Chojnacka (1931-2023) had to be more circumspect, given the threat of censorship from Soviet authorities. She never featured in a solo show and specialised in weaving, partly because they could be taken at face value more readily than a painting or sculpture. In Chains, sisal ropes cascade in poetic swags from the wall and spill along the floor. It works as a thing of beauty, but also as a suggestion of the oppression that hung over any artist who showed dissent against the regime.

The works become more obviously “gendered”, to use that ungainly word, in a section entitled “The Abstract Body”. There is little doubt what Hungarian Ilona Keserü (b1933) is representing with the curvy lines on canvas of Slit or the pieces by Hannah Wilke’s Five Androgynous and Vaginal Sculptures. They are described as sensual and might have been daring in 1960, but now appear rather facile, and are made cruder by being wrought in clunky terracotta.

By contrast, in Addendum Eva Hesse (1936-70) positioned a series of papier-mache hemispheres at precise intervals on a wooden board from which long ropes hang and curl untidily on the floor. She once explained that the ropes “opposed” the regularity of the overall concept and added: “Series, serial, serial art, is another way of repeating absurdity.”

Hesse led a tumultuous life. Her family fled the Nazis in 1936 and settled in New York. Her father left home and remarried, her mother took her own life soon after, when Hesse was 10, and her own marriage failed. Eventually she found help and inspiration when she was befriended by young artists such as Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd and Yayoi Kusama. She insisted her work was feminine without making feminist statements, and in an interview in 1970 she declared: “The way to beat discrimination in art is by art. Excellence has no sex.”

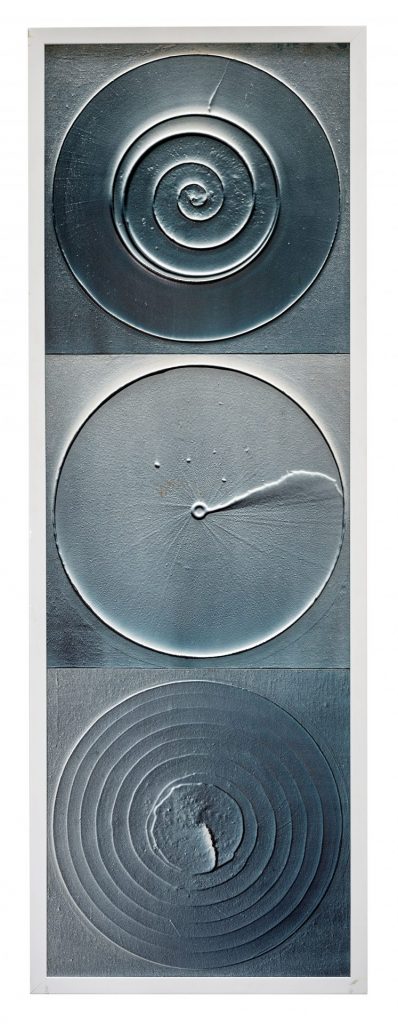

If it’s sensuous you’re after; the bronzes by Slovakian Mária Bartuszová (1936-1996) and the intimate plaster curves of Folded Figure fit the bill perfectly. To find the time to make her art as well as look after her young children, she used party balloons to cast her sculptures. The result is Untitled (Drop), a balloon filled with plaster and shaped by the pull of gravity to create a teardrop. Strangely moving.

From the tenderness of the teardrop, the exhibition moves to a hard-edged world of bronze, steel and stone in a section labelled “Making”.

There are shades of Rosie the Riveter, the fictional character, all rolled-up sleeves and muscular intent, who galvanised women to work in the factories and shipyards of wartime America, for while the sex of an artist may not determine a work’s gender there is something very “masculine” about Royal Tide III by Louise Nevelson, (1899-1988). Nevelson collected shards of wood left around her New York studio, pressed them together, painted them black, white, or in this case gold, to forge them into a cohesive whole that resembles a garage full of engine parts.

Similarly, Katmandhu #1, a jagged bronze by Dorothy Dehner (1901-1944) and the chunky Chess Pieces by Kim Lin (1936-1997) help to validate the programme notes, which applaud the subversion of “gendered hierarchies”, while the bleakness of the bronze hatched bars of Composition by Felícia Leirner (1904-1994) reflect her pain at the early death of her husband.

A delicate brass wire confection by Ruth Aiko Asawa (1926-2013) floats high in one corner. If it looks like a basket, it’s because Asawa was inspired by a basket crocheting technique she learned in 1947 during a trip to Mexico. The daughter of Japanese immigrants, Asawa’s parents were interned during the second world war and she did not see her father for six months. She was prevented from attending college in California because it was prohibited to ethnic Japanese, and she was unable to complete her degree.

“I hold no hostilities for what happened,” she said. “I blame no one. Sometimes good comes through adversity. I would not be who I am today had it not been for the internment, and I like who I am.”

As the show’s notes on the exhibition insist: “The works can be seen as an expression of radicality that pushed against the grain of machismo narratives of the postwar era.”

Few were more radical and more famous – male or female – than Bridget Riley, whose dizzying, disorientating forms dubbed as Op Art captured the imagination of the public in the swinging 60s and made her a celebrity.

She is joined in a gallery entitled “Black White Grey” by Dadamaino (1930-2004), a leading light in 1960s Milanese art whose work positively pulsates with movement, and Cuban-born Carmen Herrera (1915-2022) whose Verticals and East are uncompromisingly geometric.

Herrera, who was based in New York, did not achieve the recognition she deserved until the 2000s. “The fact that you were a woman was against you,” she once said.

Like so many others, she fell foul of “the gender bias then rampant in the art world”.

However, to explain the work of these artists as if they were forever beaten down by bias or “clouded by the spectre of relationality” (sic) or indeed to label them only as feminists (choose your own definition) would be to ignore the fact that they were a disparate group of women from around the world with different political challenges, different societies and different beliefs all reflected in diverse visions and techniques. Whether they worked in a kitchen or were exposing racism, their careers demanded determination and often courage. Feminists or not, they made their voices heard.

Maybe Carla Accardi (1924-2014), whose dramatic work Grigionero (Grey-Black) made of Sicofoil, a transparent plastic used in commercial packaging, could speak for them. She co-founded a Marxist-inspired artist group way back in 1947. It was called Rivolta femminile – Women’s Revolt.

Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction, 1950-1970 is at the Turner Contemporary in Margate until May 6