In his director’s foreword for The World Of Stonehenge exhibition at the British Museum, Hartwig Fischer writes of what he calls a “profound human desire for collective understanding and strong social relationships”.

There is in the exhibition this inscription by the archaeologist and writer Jacquetta Hawkes, written in 1967: “Every age has the Stonehenge it deserves – or desires.”

This is what makes this show prescient, and gives it a special poignancy. It is a kind of testament in ancient stone of our own slow emergence from the darkness of lockdown and worse.

It reassures us that to be human is to engage. That this is what our species has always struggled to do.

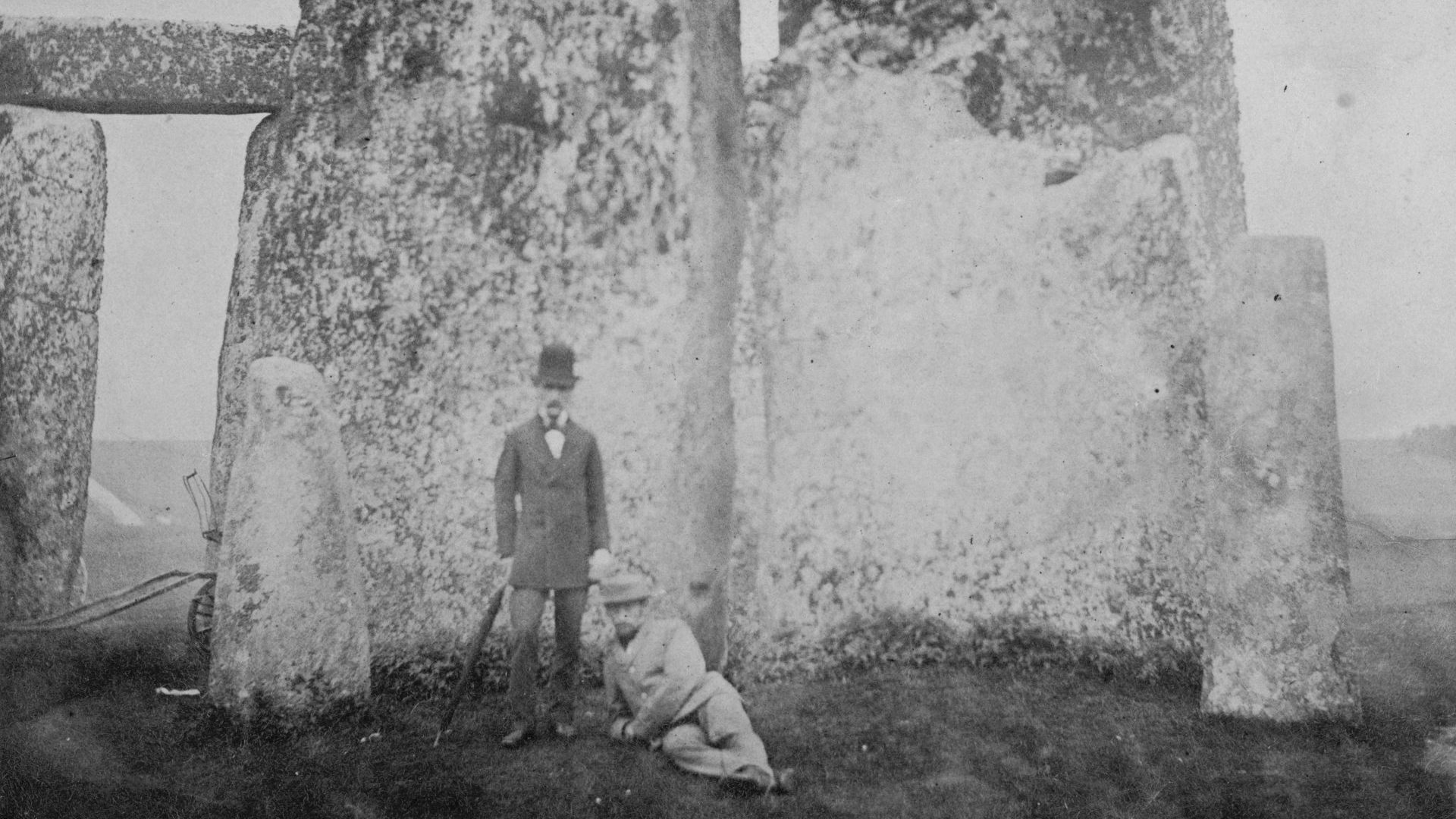

Stonehenge itself was a meeting place, a crossroads; a sacred space for the peoples who crossed back and forth from Europe to Britain and Ireland and back again.

We are a migratory species. We cannot be stopped from going to better places, safer places. This was done, too, in the times before what we understand as history began. This town hall of ancient migration was a space of quiet power.

The exhibition has its own hush, generated by the sheer awe of the new information. Forget the Great Vulva Theory, the Druid thing, all of it. That is us and those before us, reflecting back their own wondering. Stonehenge, constructed at around the same time as the Great Pyramids of Egypt, is something that was happening within our common humanity. I cannot stress enough what seems to be the innate natural quiet of the stones; of the golden collar; of all the objects assembled in a simple testament to us, back in time. It heralds all of us taking a collective breath, whether aware or not, in our march forward into the unknown.

The exhibition has objects from the BM Collection and also from museums from Northern Ireland to Germany and everywhere in between.

The World Of Stonehenge begins with a stone circle, built about 500 years before Stonehenge itself, that may have been a kind of final resting place. The stone pillars were transported from Wales, well over 100 miles away, far enough to make you wonder why people went that distance to get them. But these stones are people. Their aesthetic alone would be the allure.

The period the exhibition covers is from about 4,500 to 5,000 years ago, and that is about 100 generations. There was no writing in Britain and Ireland then, so what we know is through stone itself. The people passed on information to later generations: the meaning of being a hunter-gatherer; and later on being a farmer. These were times of change, of variability in which metal was used on the European continent over 1,000 years before it was used in Britain and Ireland. About 15,000 years ago, humans returned to Britain after the Last Ice Age. They returned to Ireland 12,000 years ago.

This was migration, immigration, and the movement was from Europe. The last 5,000 years of the recent Ice Age – about 15,000 years ago – caused the vegetation to change and with it came horse and reindeer and bison. They came across the land bridge between Britain and Europe that we now call ‘Doggerland’.

Hunters followed these animals and made campsites in England, Wales and Scotland. The new warmth caused woodlands to form for a people who saw Britain not as an island, but as a continuity.

It was Europe’s western reach. The map shows Doggerland’s widest point: between what is now The Netherlands and southern Germany, the original home of a people who became known to us as the Anglo-Saxons. The World of Stonehenge makes an utter nonsense of the ‘indigenous British’ theory of the far right. The simple and not so simple truth is that all of us citizens and/or residents of the islands of Britain and Ireland, our parents and those before them, are and were immigrants. Or descended from immigrants.

About 6,000 years ago, the area near the west coast of Scotland attracted people who lived by farming and hunting. They honoured the deer and there are remnants of bone and horns on display. There seemed to be a mystical bond that humans made with the animals they killed.

There is also evidence of the new way of life: farming. People from Europe brought with them cattle and sheep, as well as the seeds of various varieties of wheat and barley that did not exist in Britain and Ireland. Only oats had survived the Great Ice.

This farming revolution had come to Europe from south-west Asia about 11,000 years ago. We can see evidence of this migration in the magnificent polished axe from County Antrim that had been deposited in a bog between about 3,500 and 3,000BC. At that time, crops were beginning to be grown, animals domesticated, and we see the tools: the forks, the axes created by a people on the move. Monuments began to be constructed by the migrant farmers; for their social gatherings and religious ceremonies, for their burial mounds.

Stonehenge itself begins about 5,000 years ago; in a sense, it is what the exhibition calls a sermon in stone for the restless and dynamic people from Europe. Of Europe.

The exhibition’s objects – gold collars and the magnificent Nebra Sky Disc found near Leipzig and loaned to the British Museum from Halle, Germany – are the jewels in the crown of this magnificent show. The disc is an object in which people imagined the wonder of the sky. They did this because they were human. And we feel what we feel when we see this object because we are human.

There always was and is an unbreakable bond of human interconnectivity. Of movement.

Full disclosure: I am a former deputy chair of the board of trustees of the British Museum and have returned there to work on a project with the present director. So I have seen a lot of exhibitions there, some I’ve loved, some that I thought were OK, some great. But I have never seen one that has nailed what may be the unspoken inside all of us.

Just go.

Just see.

In these times of division, of false narratives, The World Of Stonehenge is the exhibition that we need now.