I am not sure when I decided to stop calling myself “African American”. Not to be “Black” either, but to be “black” – just plain “black American” – which identifies, for me, both of my heritages.

Maybe my decision to be “black” – not “Black” or “African American” – is because, when I was growing up, being called “black” was the worst thing next to the “n-word” that anybody could call you. It meant that you were ugly; stupid; lacking in any nobility. I want now to be with those abused, hated people – to stand with them.

Or maybe my new definition began while watching the film Black Panther. The moment that brought tears to my eyes was near the end, when Killmonger, the main antagonist, chose to die. He said he wanted to go to the bottom of the sea, to be with his ancestors. What touched me was that my ancestors had decided to stay alive. To endure.

By then, I had been thinking a lot about the Middle Passage, that brutal and often fatal highway extending from the Atlantic coast of West Africa, across to the Caribbean and North Carolina, where the enslaved were disembarked and sold.

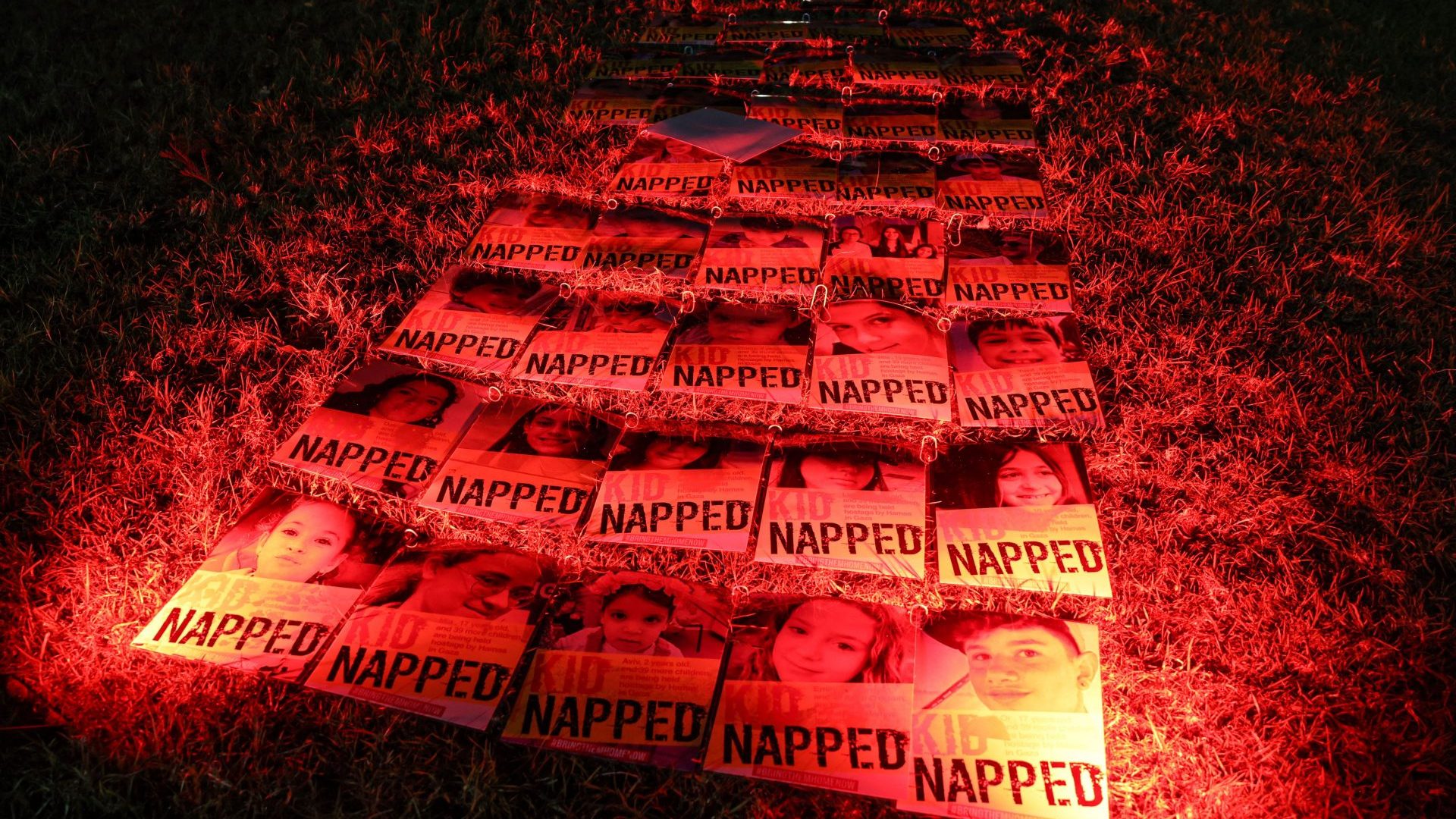

Human beings were crammed into those boats out of Africa: enemies next to enemies; clans and nations together; men chained below, women on deck, left to be sexually abused. Women led many of the revolts. There were so many that Lloyd’s of London came into existence to insure the ships and their owners. The name of the policy: “Insurrection of Cargo”.

During my work at the British Museum, I had a monthly onstage discussion series with the director, Hartwig Fischer, called “The Era Of Reclamation”. We were in conversation mainly with people of African descent, including people who could trace themselves back to Africa, who still had family in Africa. But I was not one of them. I could trace myself back to Mississippi, Tennessee and to the slave boat – no further.

During my only trip to the continent, to Accra, in the early 1990s, I cried just to see people with the faces of my uncle or aunt, these people in a faraway place who were so obviously connected to me. Yet they were not me. My Nigerian friends tell me the same thing. I love it.

That time in Accra, I had come to give a one-week course in screenwriting at the film school. When it ended, I travelled down to the Atlantic coast to the slave fortress at Elmina. It had been a holding pen back in the day – a “barracoon” – for the captured before they were stuffed into the boats.

I climbed the ramparts and looked down at the Atlantic Coast, where the ocean is high and wild. What I felt, looking at it, was this: I felt great pride, awe and wonder. I said out loud that my ancestors must have been a hell of a people to have survived the crossing – to have had children, and to have endured. To do that, their view will have consisted not only of what they had left behind; what endured in memory and custom and in prayer. They would also have become, too, developing into something different, and it is this that they gave to me to continue. So I am of “The Boat”.

At the British Museum, through my collaboration there, I began to think about what it must have taken to survive the horror and fear of the Crossing. Had something happened in the minds of those who had decided to live? Had something become new?

I learned, too, about the great Martiniquais poet, the intellectual and champion of the Caribbean, Édouard Glissant, who did believe that something changed as Africans faced what he called “The Abyss”.

We made new art forms – new music and dance and art and writing and singing. These were created from both Africanness and the New World, and drew on our encounters and mixing with our enslavers and the indigenous people of the Americas. Look at Brazil, where most enslaved Africans were shipped. Look at Jamaica, a powerhouse of Old and New World “mélange”. Look at South Carolina, at those who have held on to what they were taken away from – and made something rich and deep in response.

My “brother from another mother”, the British Nigerian artist Lanre Olagoke, born in London and who spent his childhood in Nigeria, is descended from royalty. His face is the very face of the Benin Bronzes at the museum. He has made a painting that he calls Africa Is Not a Country.

I think, in our need and our love, too many of us have relegated this mighty bit of the continent below the Sahara to a kind of country. We must not. Africa is nations and peoples as diverse and as different as those in Europe. For its own sake and ours, we must stop romanticising and fantasising its history and peoples.

A few years ago, National Geographic asked me to send them a sample of my matrilineal DNA, to trace my ancestry. The report concluded that my group was “west African with a few types shared with eastern and south-eastern Africans,” but that, after that “your genetic clues get murky… and your DNA trail goes cold.”

My DNA runs cold.

I will always use Africa as part of my identity, but not all of it. I will write the capital “B” in the word “Black” as a sign of respect.

I tell my young friend, who is British Nigerian and can trace her descent all the way back, that I want her young son, Oba, who is Nigerian on both sides, to define himself in all the persons that he is and to not be a citizen of a country called “Africa”.

He must find and create his own identity – even if it takes most of his life to do it.