Everyone knows what victory looks like. A sporting hero brandishing a trophy. A ticker tape welcome for conquering soldiers. A glorious drum-beating, trumpet-blowing parade.

But what really does victory amount to? In Victory! The Making of Heroes at the Musée de l’Armée in Paris (until January 28) the reality and repercussions of victory are examined, not with gung-ho triumphalism, as the title might suggest, but in an unexpectedly nuanced way.

With its array of statues, trophies, coins and images, the show, which is being held ahead of the Paris Olympic Games next year, tracks the glorification of victory back into ancient history, and it hints at the note of hollowness that can often be heard amid all that triumphalism.

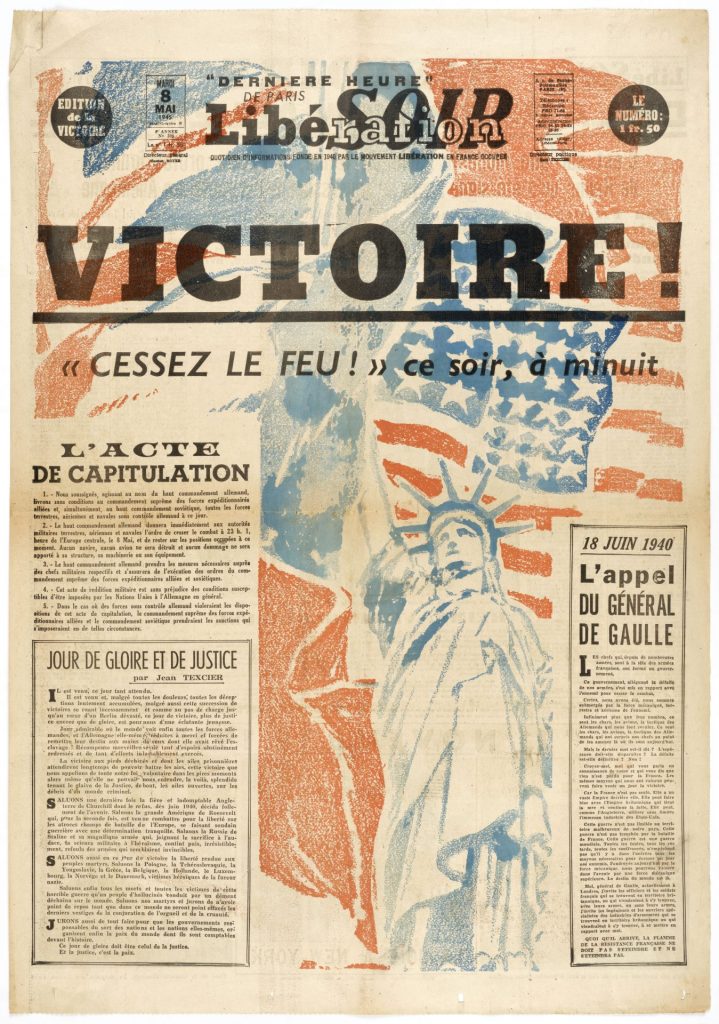

The museum is an appropriate setting, given that it is part of the Hôtel National des Invalides, founded by Louis XIV in 1670 to care for disabled war veterans. Great names of history appear in the exhibition; Genghis Khan, Nelson Mandela, Winston Churchill – though only obliquely, with a brooch sporting a diamond V sign against a sapphire Cross of Lorraine. Napoleon figures throughout but, surprisingly perhaps, the exhibition includes a caricature of a defeated Emperor being stripped of all his territories by Europe’s sovereigns at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Naturellement, “the most prestigious of France’s victorious leaders”, Charles De Gaulle, is pictured arms aloft, accepting the plaudits of the crowds.

Inevitably, military exploits take centre stage, but the exhibition also examines literary, artistic and sporting talent. The catalogue cover shows the African-American athlete Jesse Owens leaping for one of his four golds at the Berlin Olympic games of 1936, confounding Hitler’s dreams of Aryan supremacy.

Rumanian gymnast Nadia Comaneci who left the world gasping with her perfect displays at the 1976 Montreal Games is included, so too the French football team that was rewarded with a spectacular parade through Paris after thrashing Brazil in the 1998 World Cup.

Winners all. But their triumphs were soon tarnished by the cold influence of realpolitik and everyday prejudice. Owens’s Olympic triumph is seen as the great rebuke to Hitler’s racist theorising – but when the returning US Olympians were invited to the White House in 1936, Owens was excluded. Only white athletes were allowed. His victory had a much deeper resonance than is often understood.

Comaneci found herself caught up in Cold War politics. She had been awarded the Hero of Socialist Labour medal, but when her gymnastics teacher won political asylum in the west, Nadia was subject to increased surveillance by the Romanian political police and banned from going abroad. In November 1989 she crossed the Hungarian border on foot and sought asylum in the United States.

As for the French World Cup champions of 1998, their victory was hailed for being almost as meaningful as the liberation of Paris in 1944. A racially mixed team, the players of that great side were held up as representatives of a confident, new, world beating, multi-ethnic France, that had rubbished the claims of the far right that immigration was damaging the country.

But last year, after France lost to Argentina in the World Cup, online racist abuse was directed at two players who had missed penalties. Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally party continues to make inroads with voters, and the suburbs of Paris are far from being a “shining example” of multicultural amity.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, a copy of a bas-relief from the temple of Bayon built by the Khmer (Cambodian) king Jayavarman VII (1181-1218) tells the story in fabulous detail of how he defeated the enemies who had sacked his capital. There he is in all his pomp on his royal carriage, protected by ranks of troops.

In another image of triumphalism, the Japanese army marches and rides on horseback in full regalia with drums and guns, horns and tambourines to commemorate its victory over Russia in 1906. In an oil painting by Francois Flameng of the Victory Parade of July 14, 1919, the French and allied military leaders process under the Arc de Triomphe led by Marshals Joseph Joffre and Ferdinand Foch. It’s a grand scene. Victory was theirs.

But a parade can also be one of humiliation. In the drawing Surrender of Prussian troops after the capture of the city of Erfurt by Benjamin Zix, the beaten soldiers are rounded up by Napoleon after his victory at Jena and Auerstaedt in 1806 and forced to file past the French, and surrender their arms by stacking them in piles.

More shaming, 57,000 German PoWs were marched through Moscow in July 1944 after Hitler’s failed attempt to defeat the USSR, in a clever propaganda stunt by Stalin to encourage the Russian people to believe victory was within reach.

But what are our heroes really marching about? What are the statues, the posters and images actually celebrating? One of the most potent images of World War Two is the photograph Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, which captured the moment when six marines raised the Stars and Stripes during the battle between US forces and the Japanese. It became the inspiration for the Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery in Washington DC.

“Among the men who fought… uncommon valour was a common virtue,” said Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander of the Pacific Ocean Areas. Yet, 6,821 Americans were killed and 19,217 wounded – more casualties than the 20,000-strong Japanese who, almost all of whom chose death rather than surrender. It was a US victory, no doubt, but at a terrible price, particularly as military experts judged that the island was useless to the army as a staging point and unsuitable as a naval base.

As for the hundreds of thousands of French and Germans who died at Verdun in World War 1, the memorial of that terrible encounter is portrayed in a poster which dramatises the long steep steps to the tower, on top of which broods the illustrious Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne, broadsword in hand. Between February and December 1916, the combatants slogged it out in the muddy, bloody fields along the banks of the River Meuse. The order went out, not one inch of national territory was to be ceded – but it was not until the summer of 1917 that the French reoccupied all of the ground lost between February and June 1916.

That battle has come to embody an abiding sense of national pride in the courage, endurance and terrible sacrifice made by the soldiers. Around 163,000 French were killed and 140,000 Germans. Other estimates claim that the French lost 377,000 men and the Germans 330,000.

One aspect of warfare that went largely unnoticed and untreated was the mental suffering of combatants. In the two world wars, the consequences of psychological strain would have been dismissed as shell shock, something for a soldier to live with. In the most egregious cases, it was taken as a sign of cowardice, for which the penalty could be death.

Nowadays, the personal cost of victory for soldiers who survive is viewed in a very different light. Professor Patrick Clervoy, who was a member of the NATO working Group on stress and psychological support, highlights the trauma of the Gulf War of 1990-91 in which Western allied forces drove Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait. Writing in the exhibition catalogue, he recalls how after weeks of aerial bombardment the Iraqi army was swept aside in four days. In the United States the triumph was acclaimed with the traditional parade through the streets of Broadway under a shower of confetti.

“Victories are beautiful,” he writes. “The crowd admires the troops parading in full uniform, while the brass band plays a lively march. The medals jump on proud chests. But as soon as the parade is over, as soon as he returns home, the veteran finds his cracks. Cruel images remain imprinted in the depths of his heart.”

A programme set up by the US Military found that between 2001 and 2010 after the ill-conceived wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, there were more deaths by suicide than there had been in combat. In another sombre statistic it was found that one in five Americans who committed suicide was a veteran.

In poignant contrast to the triumphant return of the troops in 1991 a solitary anonymous figure is featured, a veteran in smart suit, military tie and a row of medals holding a small placard reading Gulf War Syndrome. Killing our Own.

“Victory is not the end of the conflict,” says Clervoy. “Conflicts never end. Victory is the epilogue of a series of battles. It does not guarantee anything about the future and above all it does not reassure veterans.”