Back in July 1974, I sat in a taverna watching an elderly Greek man marching up and down a pebble beach in the fading light, a rusty-looking rifle over one shoulder.

“Old Nikos thinks he can repel the Turks on his own,” laughed one of the other men in the taverna on the sleepy island of Samothraki, in the northern Aegean.

It was a far cry from the scenes we had witnessed in Turkey just a few days previously. There, you couldn’t take a train without being joined by hundreds of military reservists in full uniform, heavily armed and psyched for battle.

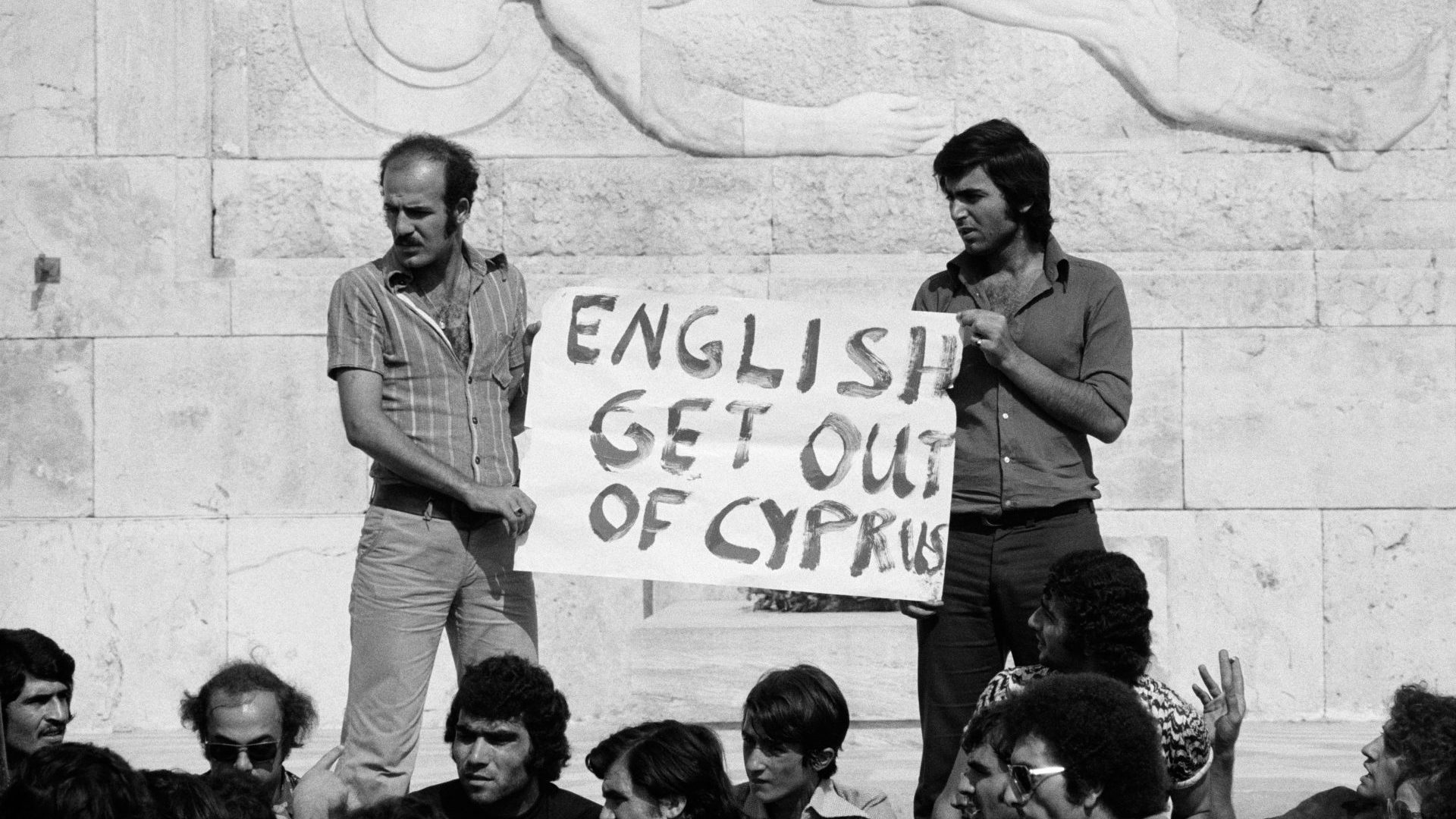

Five hundred miles south-east of Samothraki, the Turks had taken over parts of northern Cyprus. That invasion had quickly led to the overthrow of the right wing military junta in Athens and the fall of the ultra-nationalist government in Cyprus, whose ambition had been unification with Greece.

In the immediate aftermath of Turkey’s action there was relief on a number of counts: the hated junta was gone; so too its hard-right Cypriot puppet, which had come close to assassinating the country’s president, Archbishop Makarios III, before he managed to slip out through one of the British bases on the island. A possible genocide against ethnic Turks had also been thwarted.

The partition of Cyprus created large numbers of refugees, and in 2004, Greek Cypriots voted in a referendum to reject unification plans by a margin of 76%. Today the whole island of Cyprus (excluding the two sovereign UK bases) is in the EU, though in practice this really applies only to the Greek sector.

That summer in 1974, I was travelling from Istanbul to the far east of Turkey, at Lake Van, before heading back west to island-hop across the Aegean.

At the British consulate in Istanbul we asked whether it was safe to travel so far east. The diplomat on the desk turned and shouted to a colleague: “Charles, these chaps want to know if it’s safe to travel east; have you seen what it says in today’s Telegraph?”

We ventured no further than Adıyaman – a city that would be devastated in the 2023 earthquakes – before returning to Ankara with the aim of heading for Antalya on the Mediterranean coast. We bought bus tickets at Ankara, and were surprised to find only another half a dozen seats had been sold. We met a young teacher who frowned as he headed back to the sales office with our tickets. Returning with our money and no tickets, he told us that the Turkish invasion of Cyprus was due to be launched from Antalya the next day. It was no place for tourists.

Next morning, our Turkish friend insisted he treat us to breakfast near the British embassy. That traditional Turkish breakfast consisted largely of tripe soup. I managed to pour most of it into a plant pot.

Back in 1925, Cyprus, formerly a British protectorate under the terms of a deal with the Ottoman empire, became a British colony. Other parts of the collapsed empire that came under British rule included the Mandate of Palestine and Iraq.

It’s sad to consider that, had its colonial masters not repeatedly sought to divide and rule the citizens of Cyprus, the terrible events of 1974 might never have happened, and that old man would not have had to march up and down the beach with his broken gun.