Standing on a street in Guernsey, it’s hard to tell exactly where in the world you are. It looks like Britain – but it isn’t. This impression was made even more powerful by the arrival of the 19th biennial Island Games. It was meant to have taken place last year, but Covid made that impossible. A variety of languages, nationalities and cultures descended on the small island this year, including competitors from neighbouring Channel Islands, and also Anglesey, Menorca, the Faroe Islands and even the Cayman Islands.

The week of competition includes all the usual events – running, shooting, sailing, cycling and more. The difference here is that European record holders race alongside club amateurs; professionals against hobbyists. The hotels are all booked up, and for the duration of the games it feels as if Guernsey has become the epicentre of a super-sized village fete, bunting and flowers included.

I wonder if the government back in Westminster should be taking notes on how the Channel Islands seem able to play nicely with others, welcoming friends with open arms rather than sulking in a corner or pretending not to care. Given our government’s current insular mentality, I was surprised that the UK was not competing.

As I drive around the island, I see a technicolour display of flags adorning houses and cafes. Estonian, Scandinavian and even, bewilderingly, French flags are proudly on display. “French?” I ask my boyfriend, a native Guern, “but they’re not competing?” He shrugs, “probably for the Tour de France. Or maybe they just don’t want to be forgotten.”

Guernsey’s links to France run deep – the locals call themselves ânes, the French word that means, slightly bizarrely, “donkey”. Until 1971, property law on Guernsey was still conducted in French, and if you look out from St Peter Port on a clear day you can see the shadow of France, separated by fewer than 30 miles of sea, but many more miles of red tape.

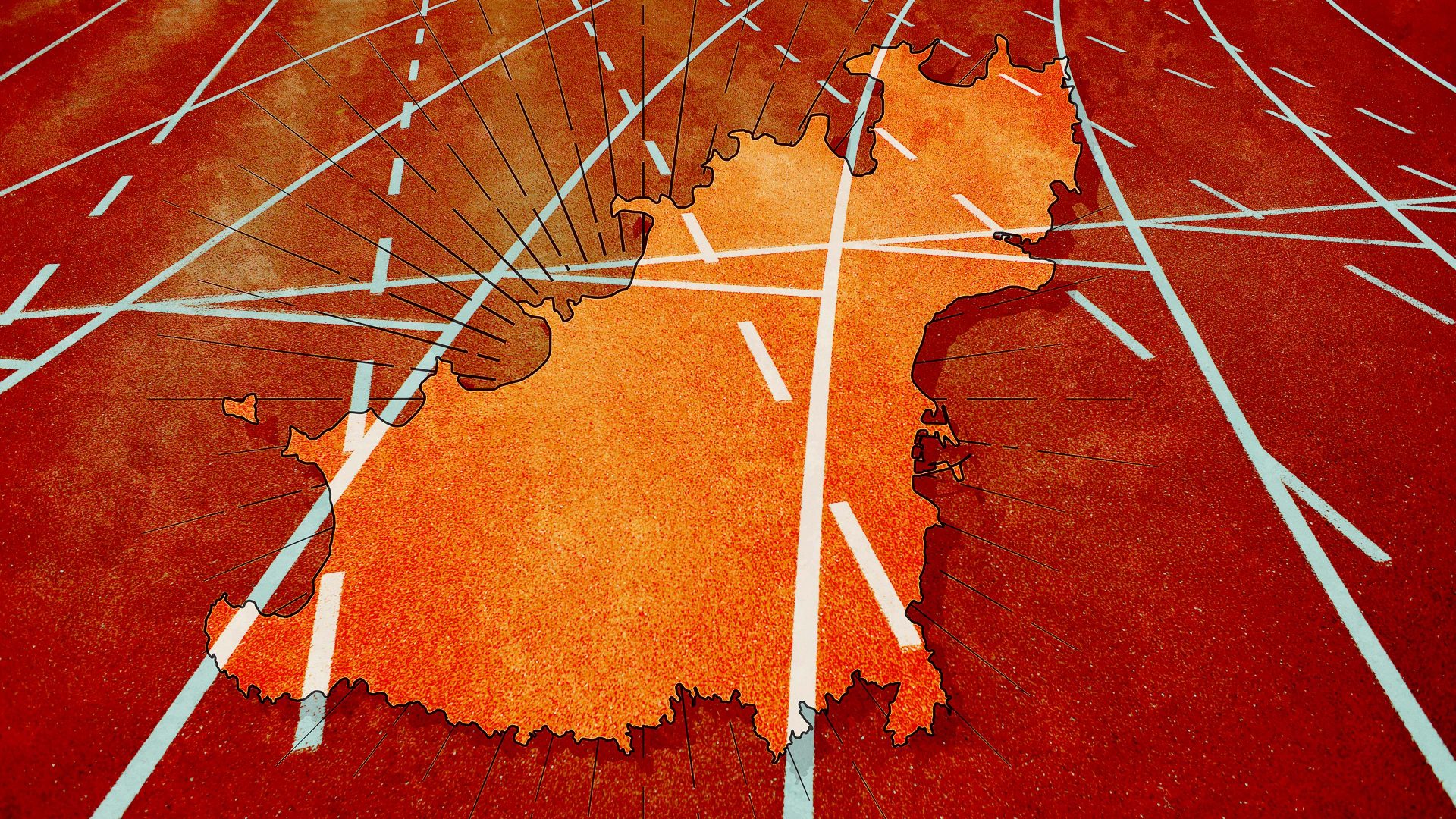

Like the other Channel Islands, Guernsey left the EU along with the UK. But while signatures on bits of paper can change the law, they can’t change history. Guernsey’s culture is still ostensibly mainland European, because relations with the continent have shaped every part of its identity. The street signs are in French, and the landscapes of the coast were immortalised by Renoir. More sinister are the old German bunkers, a reminder of the darkest moment in the Channel Islands’ modern history. The strongest evidence of a British presence are the pounds in your pocket.

As for the games, Greenland participated this year. Are they an island? They were welcomed all the same, and won two gold medals in the badminton. As I watched the medal ceremony for the women’s 400m hurdles, the flags were raised and the national anthem of Jersey blared out across the stadium, almost packed to its capacity of 5,000. Fans waved an assortment of flags, many of which I didn’t realise existed.

Despite feeling both proudly European and international, the island has a close, albeit complicated, relationship with the continent. Perhaps that is why it holds tightly to its European links: because it understands the importance of interdependency, seeing its multifaceted national character as a strength, not a weakness. That sense of strength was reinforced by the final result of the games: winning 145 medals, including 54 golds, Guernsey came first.