Fifty years after the death of Picasso, on April 8 1973, it is a mark of the artist’s unique standing that Spain, the country of his birth, has joined forces with his adopted country, France, to celebrate his life and legacy in a year-long series of events and exhibitions across Europe and North America.

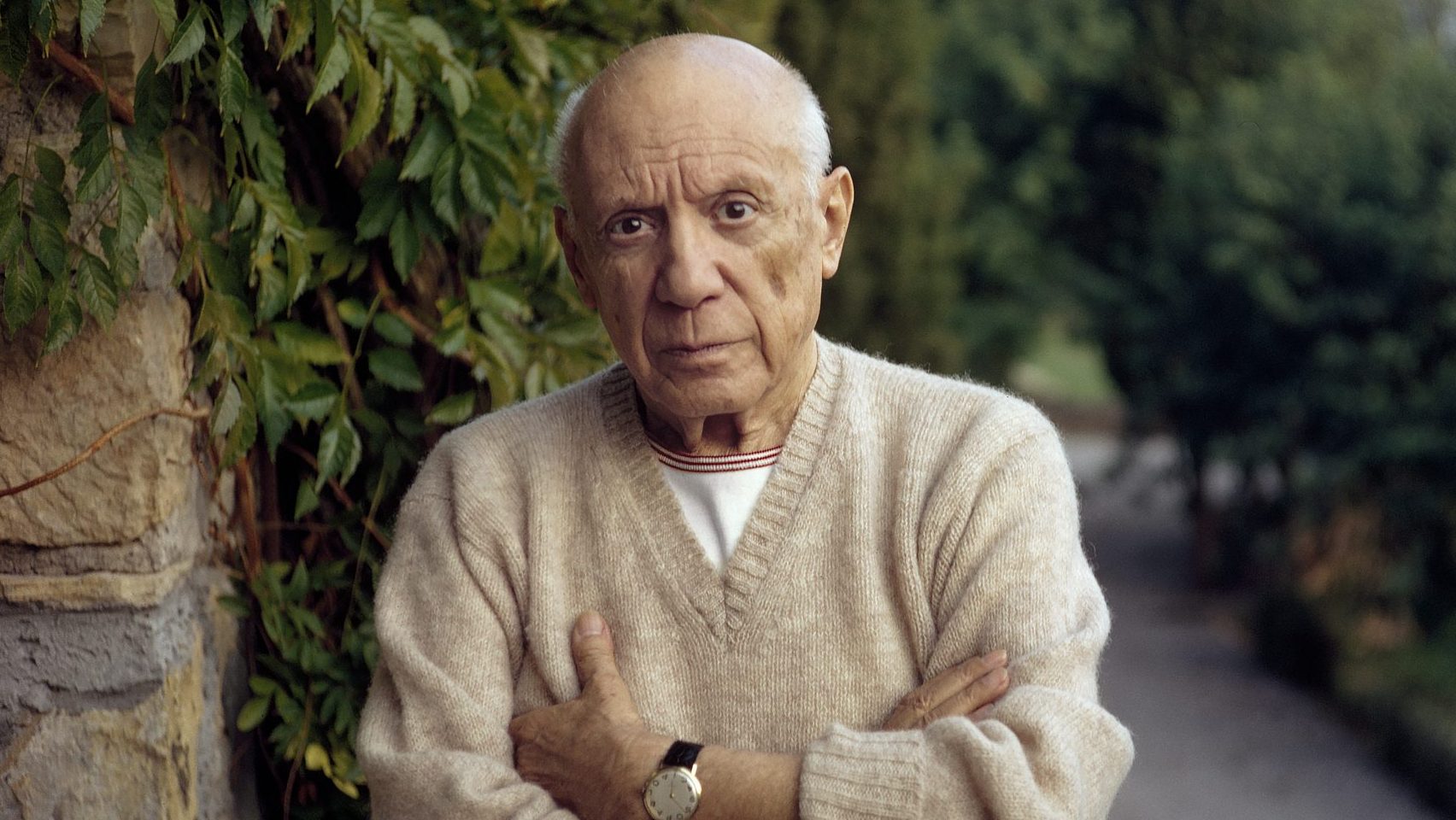

In his final years he rarely ventured beyond the barbed-wire boundaries of his 17-acre estate in south-eastern France, but when he died, Picasso was heralded as a hero by museum directors, artists and statesmen.

Today, despite bearing the rather unmodish “genius” label, and his even less endearing tendency towards bullying and misogyny, Picasso is as powerful a presence as he was not just in 1973, but across the 20th century.

The extent of his impact on the colour and texture of the last century can be gauged in the posthumous tribute offered by Thomas Messer, the director of the Guggenheim Museum New York, who said: “Not only is the art of the first half of this century unthinkable without Picasso, but I suspect the world itself would have been different and quite unimaginable without him.”

Looking back at key moments in the past, Picasso is there in the corner of our vision: cubism remains a form of shorthand for modern art, and arguably for 20th-century modernity itself; Guernica is an anti-war icon of such continuing potency that in 2022, diplomats posed in solidarity with their Ukrainian counterpart in front of a tapestry of the painting at the UN’s headquarters in New York. In diverse ways Picasso has been formative in developing the lexicon of contemporary culture.

In his lifetime, Picasso enjoyed the sort of flamboyant international celebrity that is ubiquitous today, and in the 1950s and 60s, he repeatedly broke the record for the most expensive painting ever sold by a living artist. In death he has been no less trailblazing, and the Picasso brand pioneered the rampant commercialism hardwired into 21st-century experience.

The Picasso name has been used to sell everything from ties and mugs to perfume, his signature licensed to Citroën, which used the artist’s name to sell its first car of the new millennium. The Tate Gallery’s 1960 Picasso retrospective sparked a summer of Picassomania and is recognised by some as the first “blockbuster” exhibition; 20 years later, it was Picasso again who “ushered in a new era of blockbuster exhibitions” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

It’s no wonder then that the Musée National Picasso-Paris presents Picasso as an evergreen, perpetually inspiring artist in its current show The Collection in a New Light!, a highlight of this year’s official celebrations. Curated by the fashion designer Paul Smith, it makes the case for “Picasso today”, with work by contemporary artists Guillermo Kuitca, Obi Okigbo, Mickalene Thomas and Chéri Samba distributed through the show. According to the museum’s president, Cécile Debray, “Picasso’s work remains as enduring as ever. People have always looked at it, and artists have always been inspired and stimulated by it.”

It’s a smart move by the museum, and perhaps an attempt to head off critics who feel that Picasso is today more than anything a symbol of toxic masculinity, whose influence on younger generations of artists is on the wane. Certainly, the anniversary year comes at a particularly sensitive moment, as curators, galleries and commentators continue to overhaul the white male-dominated canon, a process from which the man who once described women as “either goddesses or doormats”, emerges as an arch offender.

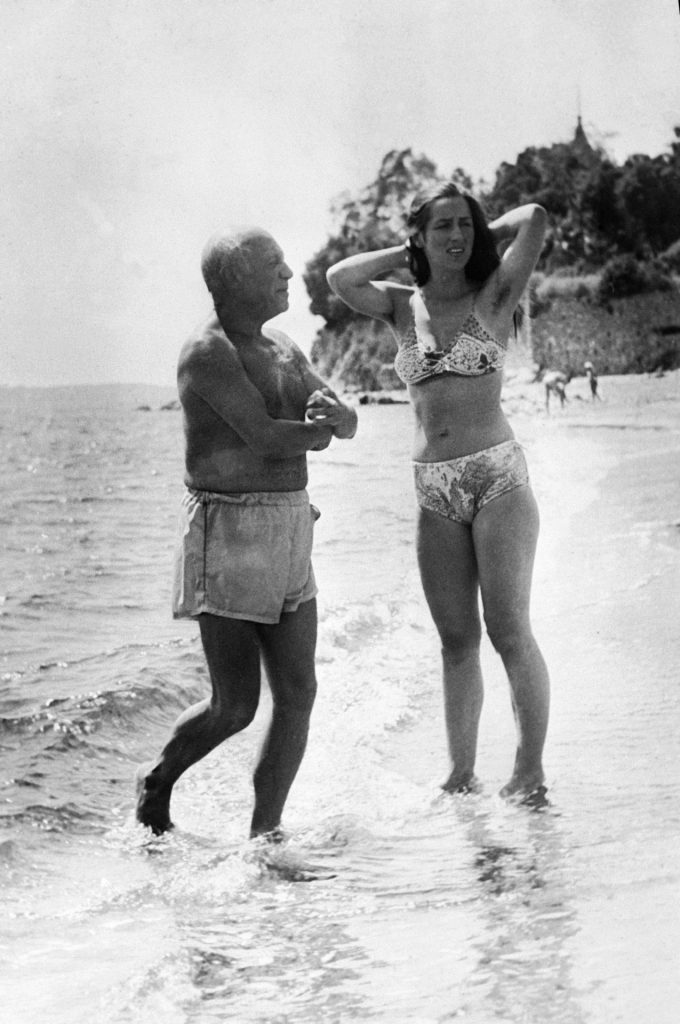

While the charges against Picasso are too numerous to itemise here, it’s worth noting that the artist had an Old Testament approach to visiting the perceived sins of his wives and lovers on their children. When in 1964 Françoise Gilot, Picasso’s partner of 10 years and the only woman ever to have left him, published her tell-all memoir Life with Picasso, he barred their children, Claude and Paloma, from his house, seeing them only rarely thereafter. If nothing else, this behaviour ensured that Picasso’s destructive hand continued to wreak havoc after his death.

Horrors ensued: his second wife, Jacqueline Roque, refused to allow several children and grandchildren to attend Picasso’s funeral, an incident that apparently drove his 24-year-old grandson, Pablito, to drink a bottle of bleach, which killed him three months later. Pablito’s father, Paulo, died from alcoholism two years later aged 54, and in 1977 Picasso’s former lover Marie-Thérèse Walter hanged herself. Roque, who Picasso’s biographer, John Richardson, described as being “obsessively in love with him”, also took her own life in 1986.

According to Pablito’s sister, Marina, who in 2001 wrote a blistering account of her grandfather’s cruelty, Picasso thrived on the suffering of those who loved him: “He needed blood to sign each of his paintings: my father’s blood, my brother’s, my mother’s, my grandmother’s, and mine. He needed the blood of those who loved him.”

Those who survived were ensnared in protracted and very public legal wranglings, brought about by Picasso’s failure to write a will. His vast estate, estimated to have comprised billions of dollars’ worth of artworks, properties, stocks and bonds, cash and gold took six years to settle between the seven heirs, at a cost of £24.5m.

There is a long tradition of allowing male genius carte blanche – Auguste Rodin and Lucian Freud spring immediately to mind – but Picasso’s work is surely unique in being granted a moral integrity that defies our knowledge of the man himself. The justified fury aimed at sexual abusers such as Paul Gauguin and Eric Gill (lesser artists, admittedly) has tainted their work; Guernica guarantees Picasso a place as an icon of global peace, despite the deadly conflict he caused within his own family.

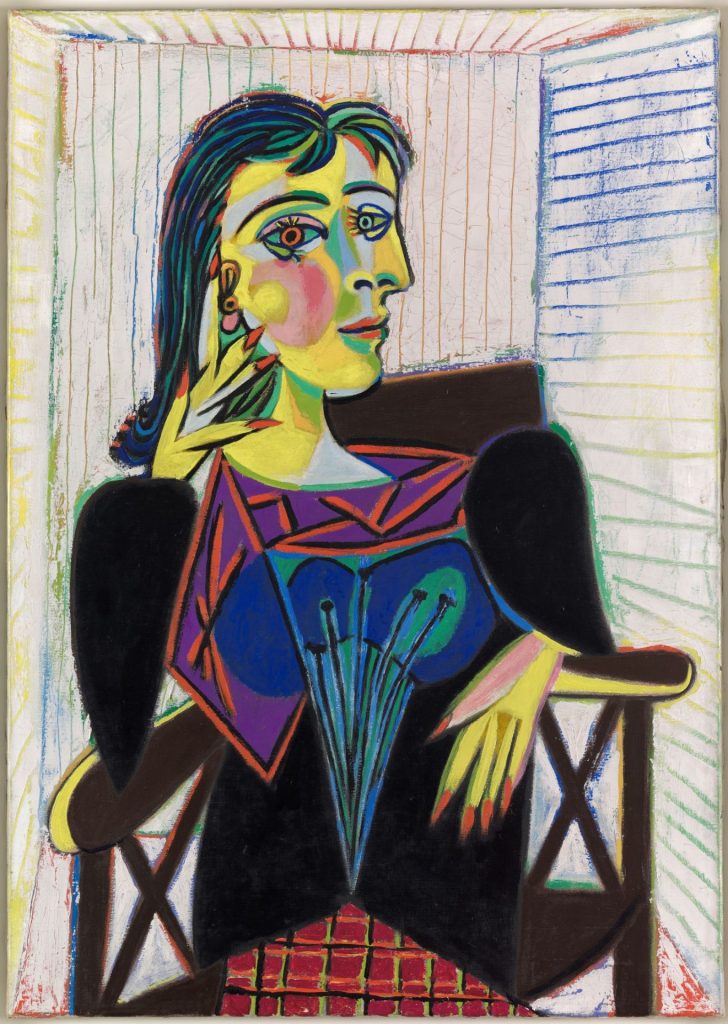

The extent to which Picasso transcends current debates and controversies was strikingly illustrated in 2018, when Tate Modern staged its first solo show dedicated to the artist. Picasso 1932 – Love, Fame, Tragedy focused on what his biographer described as the artist’s “year of wonders”, a period of unprecedented creativity inspired in no small measure by his relationship with his much younger lover, Marie-Thérèse Walter.

Tate, a gallery that has been repeatedly criticised for excessive attention to visitors’ potential sensitivities, with trigger warnings and labelling that the critic Waldemar Januszczak described as “wokeish drivel”, opened this exhibition six months after #MeToo was reignited following revelations of Harvey Weinstein’s sexual abuse. Rather than addressing the difficulties of looking at great art produced by a flawed man, Tate instead gaslit its visitors, presenting Picasso’s endless paintings of Marie-Thérèse under a suggestively enticing title, all the while urging them not to allow Picasso’s personal life to dictate their understanding of his work.

There is one show this year that tackles the man himself, to be held at New York’s Brooklyn Museum in June and curated by Hannah Gadsby, a stand-up comedian and art historian who voiced her dislike of Picasso in her Netflix show Nanette. The museum says that the exhibition will “engage some of the compelling questions young, diverse museum audiences increasingly raise about the interconnected issues of misogyny, masculinity, creativity, and ‘genius’, particularly around a complex, mythologised figure like Picasso”.

However, while those involved in organising the celebrations have acknowledged that Picasso’s treatment of women should not be ignored, the reality is that of the 50 or so events in this year’s festivities, the Brooklyn Museum’s feminist angle is the exception to the rule.

The fact is that there is no sign that Picasso is losing his appeal to either the art world or the wider public. His works continue to command record prices, they are forged and stolen more than those of any other artist, and an exhibition with his name in the title is guaranteed to pull in crowds. The sheer quantity of his work, from drawings, prints and paintings to sculptures and ceramics, makes him ubiquitous, even while his artistic influence wanes, and his personal credibility is compromised. When Citroën dropped the Picasso badge in 2018, it seemed to be more a consequence of the vast sums that had been paid in licensing fees to the Picasso estate than a matter of public decency.

It’s easy enough to put Picasso’s incredible resilience down to his genius, and the superior quality of his work. But just as there are plenty of inferior examples among the many thousands of surviving works, it is also the case that since Picasso’s first Paris exhibition in 1901, his reputation, both personal and professional, has taken countless batterings.

After his successful exhibition at the gallery of Ambroise Vollard, one of the most important art dealers in Paris, Picasso might have been satisfied to capitalise on the commercial and critical success of these early, impressionist-inspired paintings. Instead, he changed direction completely, embarking on his melancholic and far less popular Blue Period, which would be the first of multiple phases in his career.

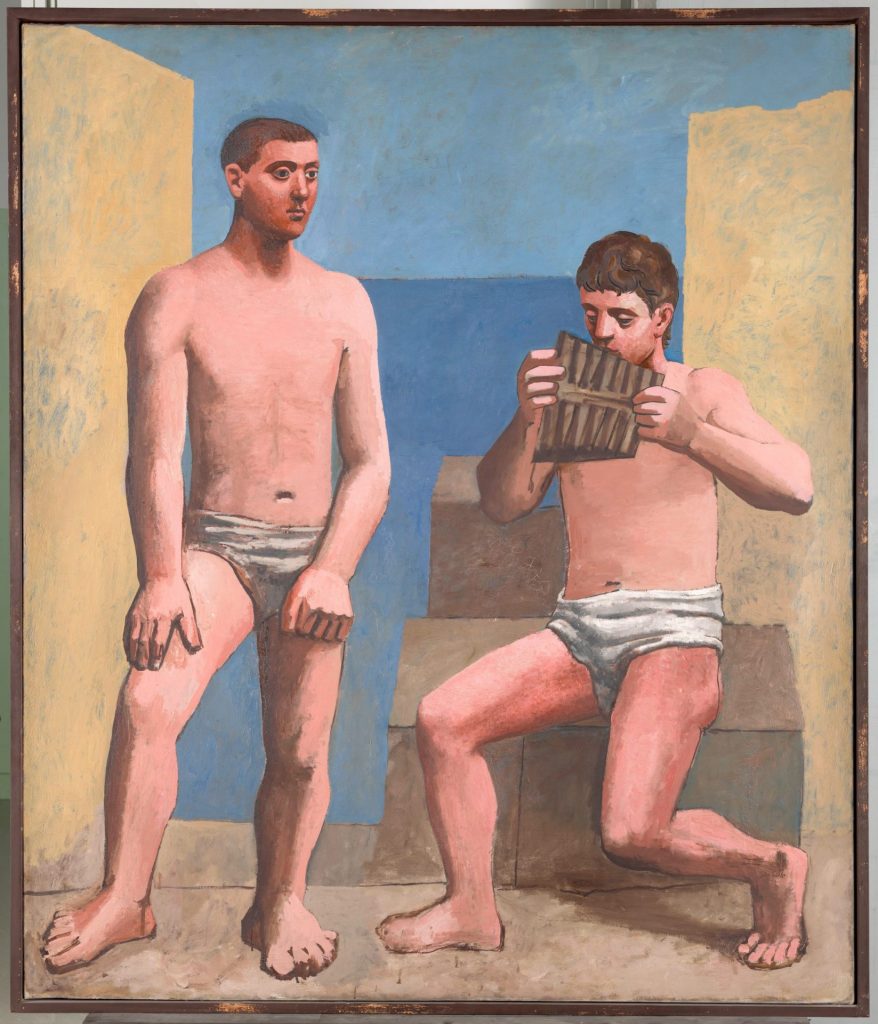

The most famous, and arguably important, was cubism, invented in around 1907 with his friend Georges Braque. Cubism was every bit as controversial as might be expected for a revolutionary approach to painting’s central conundrum – how to represent three-dimensional objects in two dimensions.

The impact of cubism on artists was immense but divisive, and in Britain where even London was an isolated cultural backwater in the years before the first world war, the 1910 exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists, which featured a single painting by Picasso and many more by Cézanne, was so scandalous that Henry Tonks, the esteemed drawing tutor at the Slade School, urged his students to stay away. The general public here was no less outraged, a state of affairs that persisted for years, so that in 1918 the Manchester Guardian reported on an article in a New York magazine, in which a doctor specialising in nervous disorders concluded that “it is not his purpose to condemn the good faith of all Cubists and Futurists, but only to say that he believes most of them may be divided into three classes – the ignorant, the dishonest or disingenuous, and the insane.”

When after the war Picasso confounded expectations by presenting an exhibition rejecting the radical experiments of cubism, and that instead reverted to a classicism at least partly inspired by the 19th-century painter Ingres, many were glad, others felt that he had betrayed the modernist cause – but everyone was surprised.

Today, perhaps, we treat art and artists slightly less seriously than once was the case. Or perhaps it is simply that after the second global conflict of the century, people were more inclined to sober assessments. In 1945, a joint exhibition of Picasso and Matisse at the V&A Museum in London marked the peace, and was understood as an affirmation of friendship between Britain and France.

For a number of British artists, toiling away in drab, bombed-out London, the exhibition was transformative, and though Francis Bacon described it as “anything but interesting”, for others, like the neo-Romantic painter John Minton, the exhibition prompted a bold use of colour and form, and an appetite for foreign travel and food.

Others felt that Picasso should be honouring the example of Guernica, 1937; perhaps it was in light of this searing condemnation of war, and the artist’s pledge to never again return to Spain while Franco was alive, that some seemed to look to Picasso almost as an oracle. One letter to the Manchester Guardian urged people to think hard about what they had seen. “It is an exhibition to be taken seriously,” wrote W Maxwell Reekie on March 7. “How can we hope for a peaceful world when active minds produce such thoughts on canvas? It is a real reflection of the way events are moving. Similarly, Mr Churchill’s speech at Fulton, Missouri, should almost be committed to memory, for both the pictures and that speech may be ‘the writing on the wall’.”

Perhaps it is a sign of the times that we rarely hear artists treated with such gravitas, but it may also be that there is rarely a figure so ubiquitous as Picasso, whose work and actions span an entire century, while remaining constantly in tune with the concerns of the day.

No wonder then that, just now, Picasso’s misogyny is the most pressing aspect of his legacy. But one thing we can take from a century’s worth of commentary is that Picasso can withstand the sort of robust interrogation the Brooklyn Museum seems set to offer, which has often been lacking in exhibitions. Picasso is too big to fail – and that makes him the ideal artist to subject to a radical feminist re-evaluation, no holds barred.

Florence Hallett is a freelance art writer and critic.

Picasso Celebration: The collection in a new light! is at the Musée National Picasso-Paris until August 27. Hannah Gadsby on Picasso at the Brooklyn Museum, June 2 to September 24. Full details of all Picasso Celebration events at celebracionpicasso.es/en/presentation