Anne de Henning was working as a press officer for a Paris fashion house

when she realised that it was not high fashion that appealed to her but high

adventure.

She persuaded a photographer in the fashion trade to teach her the basics of camerawork, and by the time she was 23 reckoned she was ready for action. The action, for any ambitious photo-journalist in 1968, was to be found in Vietnam. She bought a one-way ticket on the Trans-Siberian Railway, and crossed to Irkutsk in Russia before journeying into Japan and onwards, south, to Vietnam. Within weeks she was covering that conflict and was on the path to the lifetime of adventure she craved.

She stayed for several years, living in Hong Kong, travelling across south-east

Asia photographing tribes in Laos and Thailand, sailing on a junk across the China Sea to the Philippines. In Sarawak, she went up river in a dugout, living in a longhouse with the Dayaks in the heart of the Borneo jungle.

She was on an assignment in Kathmandu a few years later when she read that violence had broken out between East and West Pakistan.

It was April 1971. Even though the press were being expelled and the border was closed, making it impossible – in theory – to cross the frontier from India, she did not hesitate. For her, war zones were where history was made and, come what may, she was going to be a witness to what was to become East Pakistan’s struggle for liberation and its rebirth as independent Bangladesh.

She packed her gear, teamed up with three other journalists and hired a car

loaded with a few jerry cans of petrol. At first they were turned back at the

border by Indian forces, but eventually they found a place where the guards let them through.

The moment is caught in one of her photographs from Witnessing History

in the Making, a series of images that are being shown for the first time in

her home city of Paris, at the Musée National des Arts Asiatiques Guimet.

De Henning vividly recalls her time in East Pakistan: “I saw a handful of

young Mukti Bahinis [rebel fighters] stepping out of their makeshift observation post, not much more than a thatched shed flanked by a tall

bamboo pole already flying the green, red and yellow Bangladeshi flag.

“It’s early April, it’s 42 degrees. It feels empty, the atmosphere is very heavy, very quiet, but you know you are going to move toward something more noisy, more dramatic. The men were suspicious at first, rather than threatening, keeping their rifles over their shoulders, but then they greeted

me with broad smiles: ‘You are now in free Bangladesh!’.”

Bangladesh was in turmoil. West Pakistan’s Sabre jets had launched attacks on the capital, Dhaka, and West Pakistan’s president, Yahya Khan, had ordered his troops to invade.

“Kill three million of them and the rest will eat out of our hands,” he declared. Khan almost succeeded in his terrible ambition, with estimates

of the slaughter reaching the hundreds of thousands, with many more

wounded, thousands of women raped, and millions forced to flee to refugee

camps in India.

But they did not eat out of Khan’s hands. Ever since the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, the predominantly Bengali population of East Pakistan has had tense relations with the wealthier, more Islamist, West, which they regarded, with some justification, as an oppressor.

Bangladesh had a charismatic leader in Sheikh Mujibur Rahman of the All

Pakistan Awami Muslim League. Rahman led the struggle for independence with the formation of the Bangladesh Armed Forces and the Mukti Bahini, whose guerrilla tactics did much to defy and ultimately defeat the enemy.

This was the turmoil in which de Henning found herself. She was only 26 and travelling through a war zone of wrecked villages, ruined lives and vicious fighting. She had no commission from a newspaper to cover the story.

Her images show a shop with its front blown away, melancholy crowds

gathering on a street lined with black flags to symbolise the massacres that

had taken place in Dhaka. She comes across a fighter patrol that has been held up by a cow lying dead in the street. But while a soldier with a rifle steps forward apprehensively to investigate, the passers-by take no interest. Why worry about a cow when hundreds of thousands of fellow humans are being slaughtered?

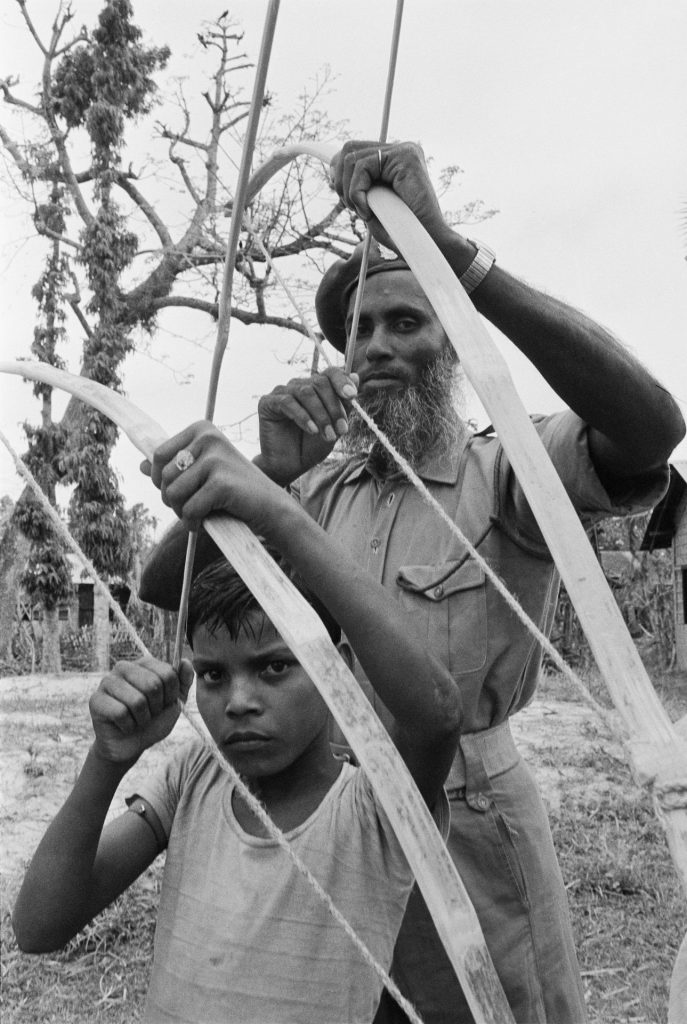

She captured the simple courage of the soldiers, who often had no uniforms, certainly no flak jackets, but fought bare-chested, wearing only their lungis (a type if skirt, usually tied around the waist). One freedom fighter strides confidently down a street, a .303 Lee Enfield rifle over one shoulder, carrying, incongruously, what looks like a woman’s handbag. A father and son prepare for battle with bows and arrows.

Inevitably, wherever she went there were angry crowds chanting Joy Bangla or Victory to Bengal. Among the most enduring memories were the pleas by people for her to beg her country for help, and the testimony of refugees like the young man who came into their train compartment to tell her that 15 friends had been killed and a female student raped.

But above all, what really struck her was the silence.

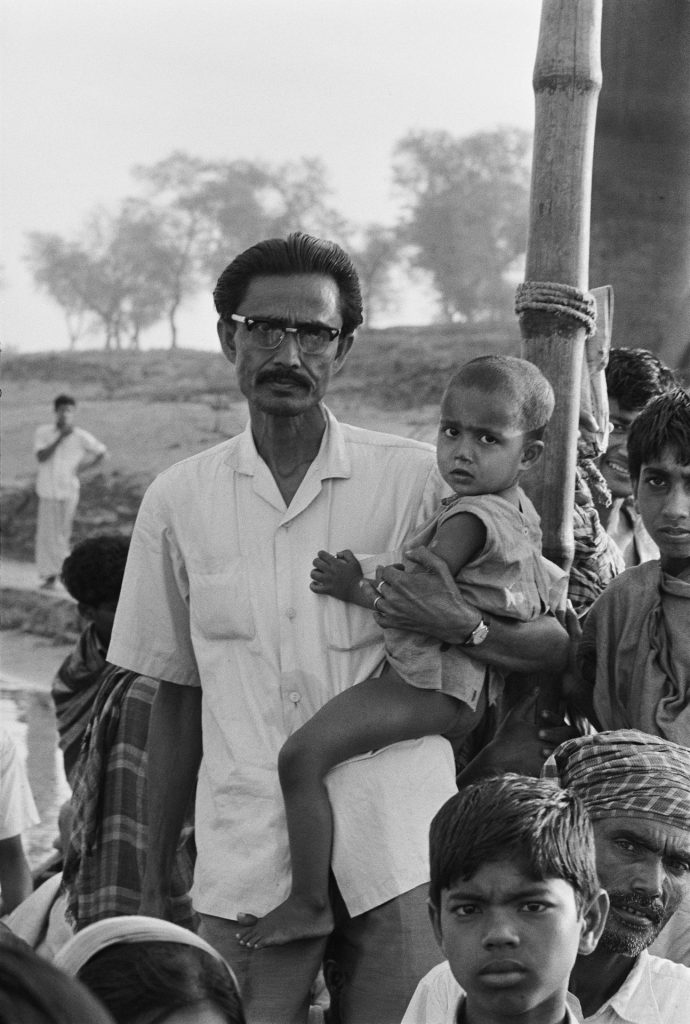

“There was an emptiness everywhere we went, a stillness,” she recalls. “Even among the refugees fleeing for their lives, there was never shouting or pushing. They were proud, you could see it in their faces. But what I have never forgotten was the anguish in the eyes.”

The eyes do tell the story. Stoic, unbeaten. Like the mother waiting to board a train carrying a baby, and with three other children each holding a seemingly random possession. One is clutching a duck by its leg and another

a transistor radio. A family led by the man of the house stride out, leaving behind the lives they have taken for granted, laden down with the few belongings they can carry. They are protected by two fighters from the Mukti Bahini.

Eyes blank with misery stare from a horse-drawn cart – a boy glares accusingly at the camera as he joins the scramble to catch the overcrowded

train to Calcutta. All of them are fleeing to an uncertain future and all are given human expression by de Henning. The poignancy of these images contrasts with the bald facts and the enormity of the suffering – 10 million people ended up in refugee camps in India, 30 million were displaced across the country.

One of the most startling images involves a West Pakistani prisoner of war who is staring angrily through the bars of his cell while the guard, the blade of a bayonet to hand, is looking at him with pure hatred.

“What I found amazing was the look of the prisoner,” says de Henning. “There is dignity, there is uncertainty, something about him which made me

understand that he was thinking, ‘why am I here?’ And actually he said to me: “We didn’t know that we were hated as much as this on this side.”

After her time in the country, she returned to Calcutta. But there was a

sequel. The war ended on December 16, 1971, when the West Pakistan army surrendered and Rahman was elected president.

He was to give a speech in April 1972, after the US officially recognised

Bangladesh as a nation, and de Henning was determined not to miss the moment.

“I had to go. I wanted to see the man who led his country to freedom and to

photograph the event. I could feel that history was in the making.”

Unusually for someone who preferred to shoot in black and white, she used colour to capture the blue, white and red stripes that decorated the ceremonial tent where Rahman was giving the speech. His head is centred on a sun, like a halo, its beams spreading out above him in an image of confidence and hope. Yet only three years later, in 1975, the president was

assassinated in a coup and nearly every image of his regime destroyed.

Only the few on show have survived and they have only recently been

discovered. One shows a crowd holding the Bangladeshi flag that they then

gave to de Henning. It sits today in the gallery next to the photograph.

“It was very moving to be given it,” she says. “It reminds me of those days

and how nothing could stop the rebels. It was in their will, their mind and the body. They had the bravery to face death.”

Witnessing History in the Making, Musée National des Arts Asiatiques Guimet, Paris, until January 23, organised by the Samdani Art Foundation in Dhaka, which champions Bangladeshi artists. Richard Holledge writes about the visual arts for the Wall Street Journal, Gulf News, FT and New European