A photograph taken in Venice in 1962 captures a pause in conversation as the artist Bice Lazzari (1900-1981) rummages in her bag, looking for a lighter perhaps, for the half-smoked cigarette that hangs from her fingers. Laughter lights the face of the modernist architect Carlo Scarpa; there’s a twinkle in the eyes of the sculptor Alberto Giacometti, but there is little doubt that it is Bice who is keeping them amused.

It’s a picture that is at once revealing and misleading: looking at it we might imagine that the abstract artist Lazzari lived at the heart of Italian artistic life, a supposition backed up by her work: urbane and at ease with the multiple strands of modernism that emerged in Europe and north America after the first world war.

And yet according to Renato Miracco, curator of Bice Lazzari: Modernist Pioneer, an exhibition at the Estorick Collection in London, “She was alone”.

Her social connections did not translate to professional ones, and even by the 1960s, when she had achieved considerable success as a designer, she was respected rather than accepted by the Italian art world.

Speaking in 1964, Lazzari described her experience: “I arrived at abstract art without any teachers or models. I knew nothing about abstract painting abroad, because of the provincial climate of cultural isolation that held sway at that time.”

Born in Venice in 1900, Bice (Beatrice) Lazzari came of age as fascism took hold in Italy. It was a difficult time, not least for artists: the spark of futurism that had set Europe alight in the years before the first world war had lost its brilliance, and Italian artists were increasingly starved of external influence, and circumscribed by politics.

Miracco writes: “In today’s interconnected world, it is difficult to understand how in the 1930s and 1940s in Italy there was no communication with the outside world.”

If times were hard for male artists, their female counterparts existed on the margins, and Miracco emphasises that they were isolated from one another as much as from the art world at large.

Belatedly but wholeheartedly honoured in this exhibition in collaboration with the Archivio Bice Lazzari in Rome, and with additional loans from private collections and the Richard Saltoun Gallery, London, Lazzari has been largely unheard of outside Italy, her reputation ensured only by the archive.

Many more women have disappeared without trace. Something of the scale of the loss is only now being understood, with a recent exhibition and book titled Women in Abstraction at the Centre Pompidou in Paris highlighting the work of more than 100 female artists working in what has previously been understood as a male preserve.

Talking about his research, Miracco said: “You open a door and cross into a parallel world. It’s unbelievable how women were struggling, with family, husband, kids and art. They had to struggle to define themselves. Some of

them stopped for years to take care of their children, others ended up doing

something else completely.”

Lazzari’s struggle began early on. She was advised against studying painting, and in 1916 she was enrolled on a drawing and decorative arts course at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice, considered more suitable for women. Later in life she would be forced to abandon painting again, when it was discovered that oil paint was gradually destroying her sight.

With characteristic resolve, Lazzari played the hand she was dealt. Miracco says: “She was absolutely committed to pursuing and making the best of her skills day by day. It’s amazing, and a lesson for us all.”

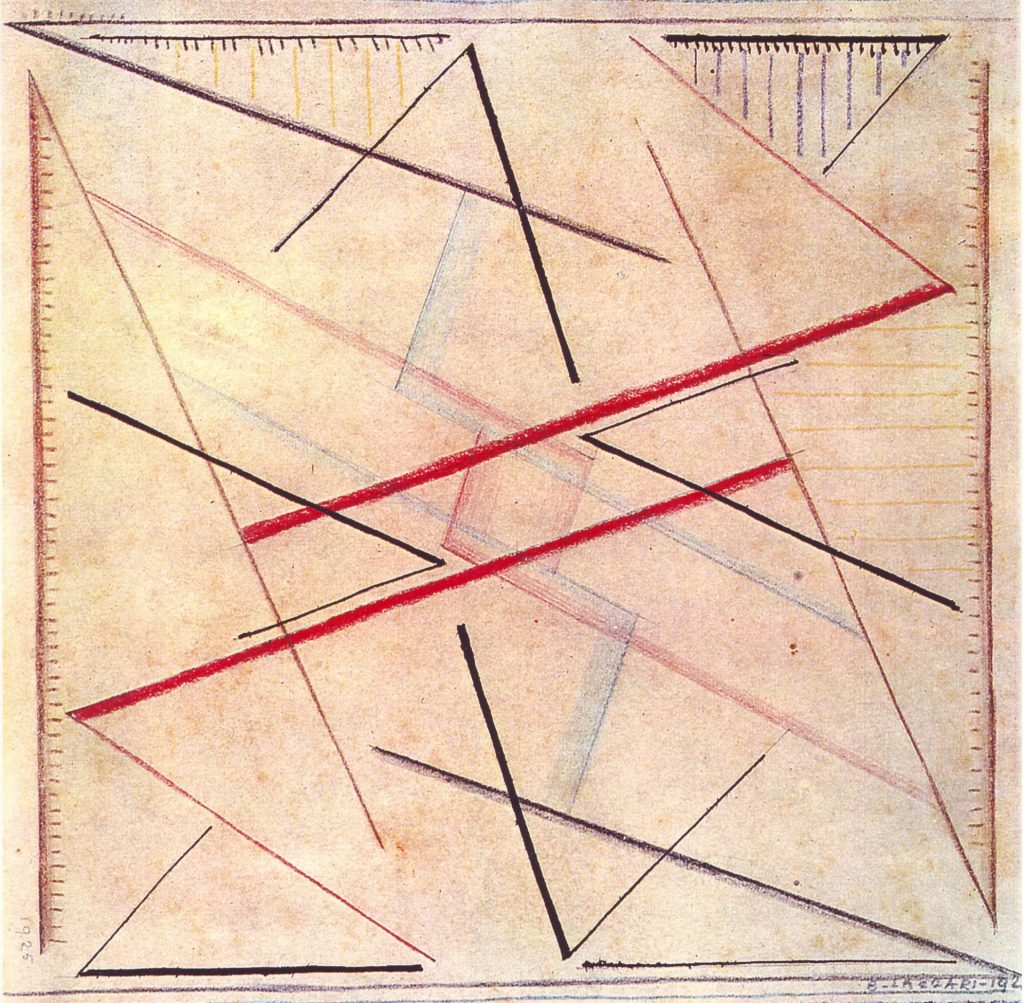

She worked in textiles but she was not constrained by them, and Lazzari’s first known abstract work, Abstraction of a Line No. 2, 1925, is a design for a piece of embroidery, its precisely placed lines and geometric forms exploring form, colour and space in a way that recalls Wassily Kandinsky’s Composition VIII of two years before.

Perhaps Lazzari knew Kandinsky’s painting, perhaps she didn’t: certainly, she aligned herself with no particular group or movement.

Writing in 1929, she expressed herself in uncompromising terms: “The spirit is tense in the overbearing urgency to give life to obscure forces that act for an inexhaustible quest for the truth. The truth of a woman face-to-face with life, who can only have one truth to tell: her own.”

Lazzari’s parents were not wealthy, and when her father died in 1928, her priority was to earn a living. In an interview in 1970, she explained: “I had to face life on a practical level and so, rather than walking around with a painting under my arm, I took a loom and started making applied art (fabrics, scarves, belts, carpets) in order to continue living in the climate I so adored – namely, freedom.”

Some of the earliest pieces in this exhibition are geometric designs for a

cushion cover, a belt and a bag that look as modern now as they did in 1929. Paint sketches from the late 1920s are freehand, and yet the forms are easily understood as textile designs, the pencil grid marked on to Red Cut, 1930, heightening the sense of warp and weft.

Working with fabrics, which drape in three dimensions rather than hanging flat, provided the seed for Lazzari’s interest in decorating architectural spaces, which would become a major aspect of her work from 1935 until the 1950s.

In 1935, she moved to Rome, where she did various stints with architects including Carlo Scarpa, and Ernesto Lapadula, undertaking a variety of

design projects including the decorative panels for propaganda exhibitions staged by the fascist regime.

During the second world war, Lazzari and her husband, Diego Rosa, worked for Gio Ponti, one of Italy’s most celebrated designers, famous for several chair designs and the Pirelli tower in Milan.

Lazzari produced fabrics, jewellery, tiles, fabrics and furnishings. These were all regarded as an appropriate pursuit for a woman, but mural painting, which she was equally occupied with, was a male preserve, and Lazzari is certainly the only Italian woman known to have worked in this field at this time.

Wall painting seems to have been profoundly significant to Lazzari, who wrote in 1957 that “When I paint a picture, I secretly think of the wall on

which I could be painting at that moment”. This did not mean that she

planned her work on a grand scale: on the contrary, the paintings in this

exhibition are all fairly modest in size, and many are very small, in notable

contrast to her male counterparts.

“I am generalising, but so many times the male needs a huge canvas!” says Miracco. “In Lazzari’s case, she was thinking about space, not size – if you enlarge the space, the message will be lost.”

Once Lazzari finally began to focus her energies on her own painting, after the war, she entered a period of transformative exuberance, exaggerated all the more by the austerity of the work that came before and after.

From the early 1950s, she paints free-flowing, organic shapes in highly textured paint and vivid colour. Though still abstract, her compositions often relate to observed reality, acknowledged in titles such as Blue Architecture, 1955, and Marine Tale, 1956, a painting that from a distance appears as a seascape, slipping into abstract form as you get closer to it.

Though Lazzari wanted to develop her own visual language, or “alphabet” as Miracco calls it, she felt the pull of observable reality: “She was struggling

with how to put herself far from the figure and achieve this other, unknown alphabet – she was back and forth.”

At certain points, colour gains overarching significance, with works from the mid-1950s dominated by gorgeous concentrations of hue. Interestingly, in White and Black, 1954, the colour that dominates the canvas is not white or black, but a brilliant orange-red.

Colour turned out to be Lazzari’s enemy. More specifically, the solvents used to thin oil paint had been slowly destroying her sight, so that in 1962 she was forced to abandon oil painting altogether.

What followed was, she told her husband in an interview from 1970, “a profound identity crisis”, prompting a complete re-evaluation of her work.

She returned to a more restrained, yet no less meaningful colour palette, rendered in pencil, crayon, tempera and acrylic. Lazzari’s work acquired a new focus, achieving, as she described it, “the lucidity of the bare minimum”.

Interestingly, though, this new phase of work, so often worked out in rhythmic, repetitive pencil marks, retains the gestural qualities of her paintings from the 1950s.

Looked at closely, her pencil lines are each unique, drawn in a quavering freehand, and often picking up the texture of the surface beneath the page.

Oddly enough, it is in works like Acrylic No. 527 from 1979 that Lazzari’s work seems at its most musical, not just because her ranks of lines resemble notation, but because the reality they seem to refer to is not an observable one.

This is, of course, literally the case: made in her last years, when her sight had almost completely gone, Lazzari’s lines, barely seen but felt through the

action of the hand, must have felt reassuringly repetitive, each one a firm connection with the world outside her own body. In their dogged persistence, they might even constitute a self-portrait of sorts.

According to Miracco, “they are the ultimate proof of compositional willpower, of intractable stubbornness and of an expressive quest”. Certainly, they offer a more accurate, if considerably starker, portrait of the

artist than the Venice 1962 photograph of Lazzari, Scarpa and Giacometti.

Bice Lazzari: Modernist Pioneer at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, 39a Canonbury Square, London N12AN, until April 24

Women in Abstraction, edited by Christine Macel, published by Thames & Hudson, £50 hardback