Kemi Badenoch, the newly-crowned leader of the Conservatives, has a difficult job on her hands. After 14 years in power and a humiliating election defeat over the summer, her party is an unfocussed mess.

The battle for the heart of the Conservative Party will probably rumble on for a while. Its depleted membership is less a broad church of people on the same team, and more a bunch of rats that failed to fight their way out of a sack. There is one issue, however, that unites most Conservative members these days: the need to take on Nigel Farage and Reform UK.

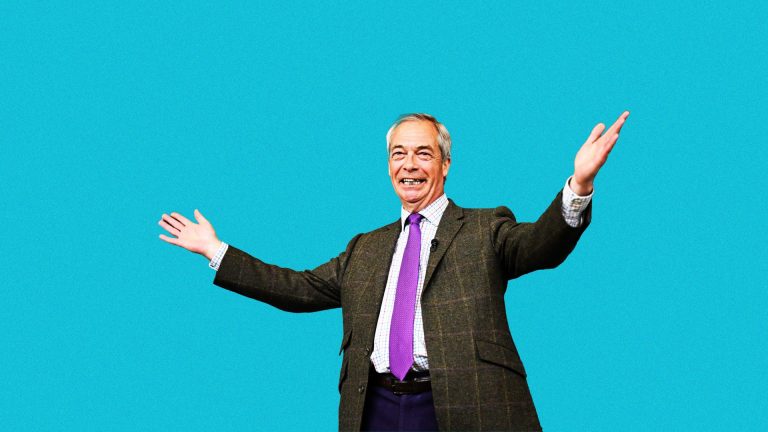

Why Farage is of such concern to Conservatives is obvious. His embrace of populism and dogged single-issue campaigning has hurt the Tories more than any other British political party. Without Farage fanning the flames on Europe, the Tories needn’t have poured petrol on themselves in 2016. His superpower is to provide simple answers to complex problems that are of particular concern to Conservative voters. Don’t like the EU? Leave! Immigration too high? Shut the borders!

This unsubtle chiselling away at the base of Tory support has threatened to collapse the party multiple times. It has forced Conservatives to make repeated lame attempts to clear bars that Farage sets impossibly high.

Badenoch has already said that leaving the European Convention on Human Rights is an impractical nonsense, and rightly so. Whether or not she can resist chasing Farage down his various rabbit holes in the coming months matters not just to Conservatives hopeful of a return to sanity, but for all of us who’d like to see the toxicity sucked out of politics.

State of the right

The state of Britain’s right has changed since Farage first entered many of our consciousness, ahead of the 2010 general election. Back then, it was easy to identify the clear dividing line between David Cameron’s Conservative Party and Nigel Farage’s Ukip. It was possible to draw a line between Ukip and the British National Party. And there was still some distinction between the BNP, the English Defence League and other extremist groups.

Nearly 15 years later, those lines have been blurred to the point of near-invisibility. In some cases, they have been deliberately smudged by mainstream politicians who borrow the language of the far-right when it suits them. The result is a public that is now more exposed than ever to previously distasteful fringe figures and ideas.

This, along with the right’s media prevalence, has allowed ideas, language and even personalities previously separated by political identity to mix freely. Now, ideas and people previously considered distasteful are thoroughly mainstream.

“In 2010, people like Nick Griffin, Tommy Robinson and to a lesser extent Nigel Farage were fringe figures who belonged to distinct political tribes,” says Paul Jackson, professor in the history of radicalism and extremism at the University of Northampton. “Voting for them or attending their rallies meant you were part of that tribe, which may have turned people who thought of themselves as moderate conservatives off.”

Now, the merging of right-wing factions has made it common to see people who wouldn’t think of themselves as radical taking part in political activism that originated on the far-right.

“The anti-lockdown marches are a prime example of this,” says Julia Ebner, leader of the Violent Extremism Lab at the University of Oxford. “Within the anti-lockdown movement were people within the mainstream who had concerns about lockdowns. But there were also people who believed conspiracy theories about Covid and vaccines that originated in fringe far-right media.”

Uniting the right

The idea of uniting the right is nothing new, but its success has been varied and gradual. In truth, the rubbing out of dividing lines between different factions and the mainstreaming of its own ideas has probably been the far-right’s greatest achievement.

One needn’t look far for examples of centre-right politicians borrowing ideas from their more radical counterparts in order to speak to voters farther along the spectrum.

The previous Tory government was not above borrowing the presentational style of the far-right when wooing voters. In May, the Home Office released a dramatic video of asylum seekers being rounded up by law enforcement, placed in handcuffs and chucked in the backs of vans, shortly after the controversial Safety of Rwanda Act had passed into law. You can support the policy or think it barbaric, but it’s pretty obvious that the Tories had a specific audience in mind when producing this clip.

Sure, it might appeal to some considering voting Reform. But it also runs the risk of walking the Tories head-first into a classic Farage trap. Shortly after the act entered law, the Reform leader slammed Rishi Sunak’s Rwanda policy as useless and set the government a new challenge, saying the only way to stop mass migration was by leaving the ECHR – now a mainstream Conservative policy.

This is where the “post-organisational” nature of the right becomes so dangerous. No matter how extreme you are willing to go with your rhetoric, there will always be people demanding you go further. Even Farage and co are starting to realise this.

If you ever take a glance at comments underneath articles written by Farage, or look at replies to his tweets, there are often examples of his own supporters asking: why are you not speaking out in support of Tommy Robinson?

Some choice examples, edited for decency:

“Nigel I have to say you’ve gone down in my estimations recently. You’d do well to reconsider what you’ve said/your views on Tommy Robinson and his supporters. I want to vote for you again next time round (sic) .. but!!”

“Support Tommy Robinson or you will become irrevelant (sic).”

“Nigel, you continue to vilify the bravest man in Britain, Tommy Robinson … You’re just as bad as the crooks who put him in Belmarsh”

We could go on, but these are just three examples from many more taken during one 24-hour period.

Reform has tried desperately to distance itself from Robinson’s supporters. Richard Tice, Reform’s deputy leader and Farage’s latest pint holder, recently sought to distinguish their party from Robinson’s fans, calling them with some derision: “that lot.”

Take a quick look through the responses from some of “that lot” to Tice on Twitter, and it’s clear many Reform voters are also supporters of Robinson.

Some believe Farage and Tice used Robinson to win voters before hanging him out to dry. Some believe the Reform men are posh wimps, scared that any association with Robinson will disbar them from the mainstream and Westminster’s nicer restaurants. Some believe they are playing a complicated game of 3D chess, working alongside Robinson.

The Blob

It’s impossible to know for sure what goes on in the heads of Farage and Tice. But what’s clear is that even when politicians try to redraw the old lines between these differing factions, the public still sees them as part of the same amorphous blob, appealing to the public via the same highly-emotive issues.

“The issues that consume the right are ultimately ones of emotion,” says Jackson. “At their most effective, they offer optimistic solutions to anxieties brought on by the perceived failure of the political elite – about immigration, crime or national identity. That can be very powerful.”

Powerful, indeed. The violent reactions to what happened in Southport were just the most recent reminder of what can happen when all manner of emotive issues are stirred together and poured down the slippery right-wing slope.

Supposed moderate Conservatives made statements, despite having no idea what had happened – in some cases referencing information they’d seen tweeted from dubious sources like Andrew Tate. The mess of misinformation was flung over the walls of far-right social media and, before you knew it, hotels housing asylum seekers were under attack. It was a near-perfect case study in how bad or dumb actors can escalate a tragedy – and it could easily be repeated.

If this all sounds alarmist, it’s worth taking a look at how “post-organisational” politics has gripped the Republican Party in America – where moderates now support the same candidate as armed militias. Or across Europe, where parties founded by former fascists and Nazis are forming governments.

So far we have managed to avoid that level of disaster in Britain, in part because our political system shuts the fringes out of power. But even that’s not much of a safeguard: with no prospect of gaining real power and no consequences for their actions, populist rabble-rousers are free to carry on raising the stakes.

Badenoch faces a choice as opposition leader, with the best part of five years in front of her. She can try to match Farage and the others to her right. Or she can break the cycle and stop playing their game on their terms.

If she chooses the former, history suggests she will fail and British politics will continue on its current toxic doom loop. If she chooses the latter, she might find that depriving extremists of their oxygen gives them less room to breathe and pollute our democratic system.