Lucia Moholy was an avant-garde Bauhaus photographer, writer, philosopher, information scientist and an intelligence operative for the British effort. She is generally remembered, if at all, as someone’s wife. That, however, is about to change.

The someone was László Moholy-Nagy, the Hungarian photographer, painter and professor, whom Lucia married in 1921. Moholy-Nagy is today celebrated as a pioneer of the photogram – the camera-less photograph – a process he worked on while teaching at the Bauhaus, the famed German art school in Weimar and, later, Dessau. These landmark experimental images were often made in uncredited collaboration with his wife. That omission set the tone for what was to come.

A new exhibition in Prague, the city of her birth, aims to highlight the many accomplishments of this forgotten figure. Lucia Moholy: Exposures at Kunsthalle Praha – a private contemporary art institution that opened in 2022 – presents around 600 photographs, microfilms, letters and audio interviews that collectively detail an indomitable character, one fuelled by curiosity and creativity, but beset by affronts and hazards – from insouciant sexism to the fog of war – each incrementally pushing her further into obscurity. This is her first major retrospective.

At the Bauhaus, Moholy was neither a student nor a teacher, but rather a privileged insider without portfolio. In addition to assisting her husband, she shot school projects, experimental nudes, still lifes of table lamps, tea infusers and coffee pots, and architectural studies of the school’s modernist buildings fragmented in the landscape by the vertical lines of pines.

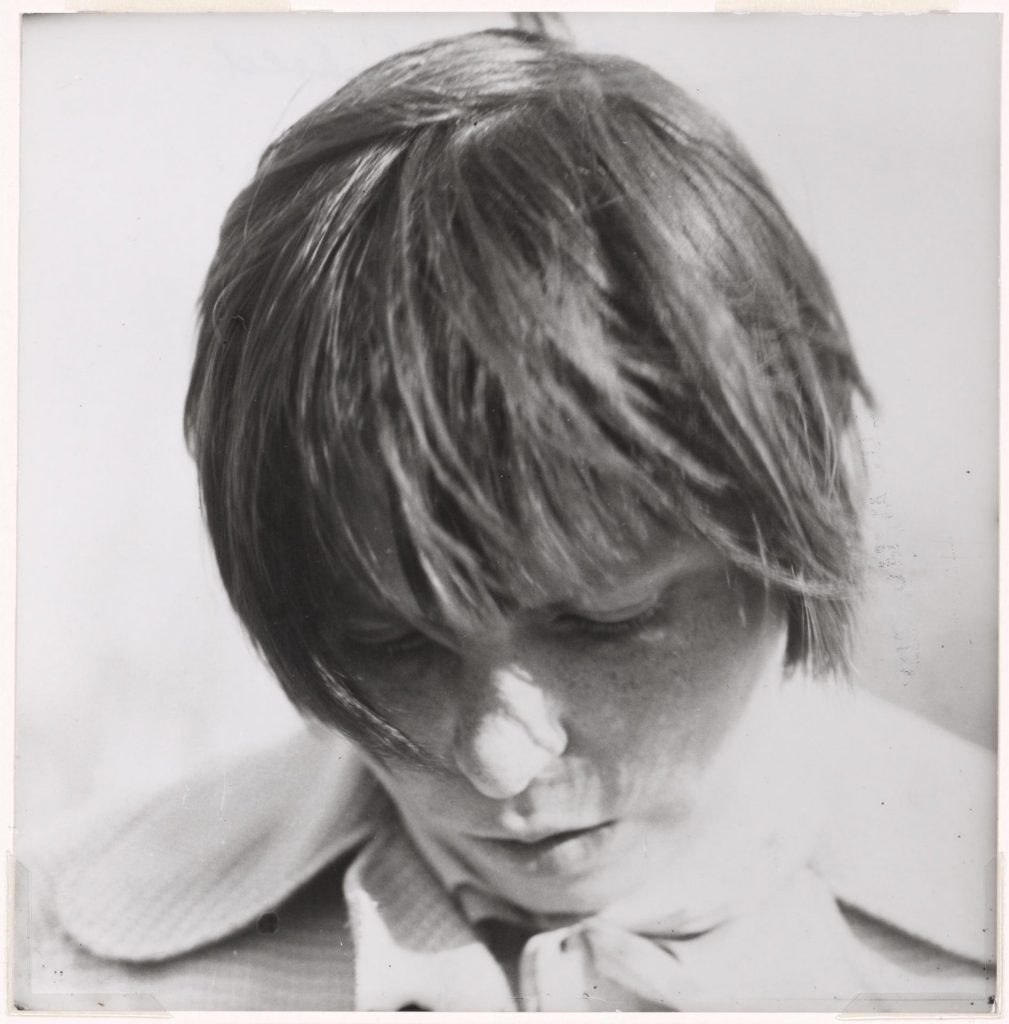

During these years she also took her most distinctive body of work, a series of enigmatic and mercurial portraits of her peers created under the principles of “new objectivity”, the German movement that rejected the more romantic, self-indulgent flourishes of expressionism. These shots of friends and colleagues amounted to something like anti-portraits – taken from above or below, the faces partly obscured by a hand, a tangle of hair or a shadow or the angle of the shot. There is a strange intimacy to her close-up, tightly cropped studies.

This important body of work was lost to Moholy when, following her separation from Moholy-Nagy and the rise of Nazism, she went into exile in Britain, leaving boxes of her original glass negatives in Germany. Told that they had been destroyed by “enemy action” during the war, she later learned that Walter Gropius, the architect and founder of the school, had taken much of the material to the US. Her photographs were repeatedly illustrated without her credit, both before the war and after. A “fully fledged conspiracy had been enacted against me,” she recalled.

The appropriation of her work, either by design or accident, by Gropius, Moholy-Nagy and others affected her in two ways: she was denied an income from works that had become valuable records of life at the Bauhaus, but also it hampered her professional progress as a photographer. In light of this outrage, the exhibition presents two kinds of exposure: one photographic, the other biographical.

She was born Lucia Schulz in Prague in 1894, and was raised in a non-practising Jewish family in the cultured milieu of the city’s German-speaking enclave. Her father, Bohumil Schulz, was a successful lawyer who would bring presents back from his travels abroad. She grew up reading Thomas Mann and Leo Tolstoy.

Aged 19, she wrote in her journal of 1913 that “the human being is a small child of nature. Art is the great child of humanity. She will form new people whose offspring we do not yet know.” We hear the voice of a fledgling philosopher: she subsequently studied philosophy, philology and art history at the University of Prague.

She met László Moholy-Nagy in Berlin in 1920 and the couple married the following year. Life at the Bauhaus was not entirely happy. “Dessau is like a place in which someone – travelling – misses their connection and must wait for the next train,” she wrote. “One would do better to never get off in this city in the first place.”

Following the couple’s separation in 1929, Moholy returned to Berlin, where she began a relationship with the communist activist Theodor Neubauer. When he was arrested by the Nazis, she fled, without her negatives, first to Paris and then to London. Her life in exile provided frustrations but also opportunities: she published A Hundred Years of Photography, 1839-1939 for Penguin Books, the first mass-market cultural history of the medium, and took portraits of the Bloomsbury Set. She spent the war years working for a microfilm service based in the V&A Museum, copying smuggled German and Japanese scientific documents.

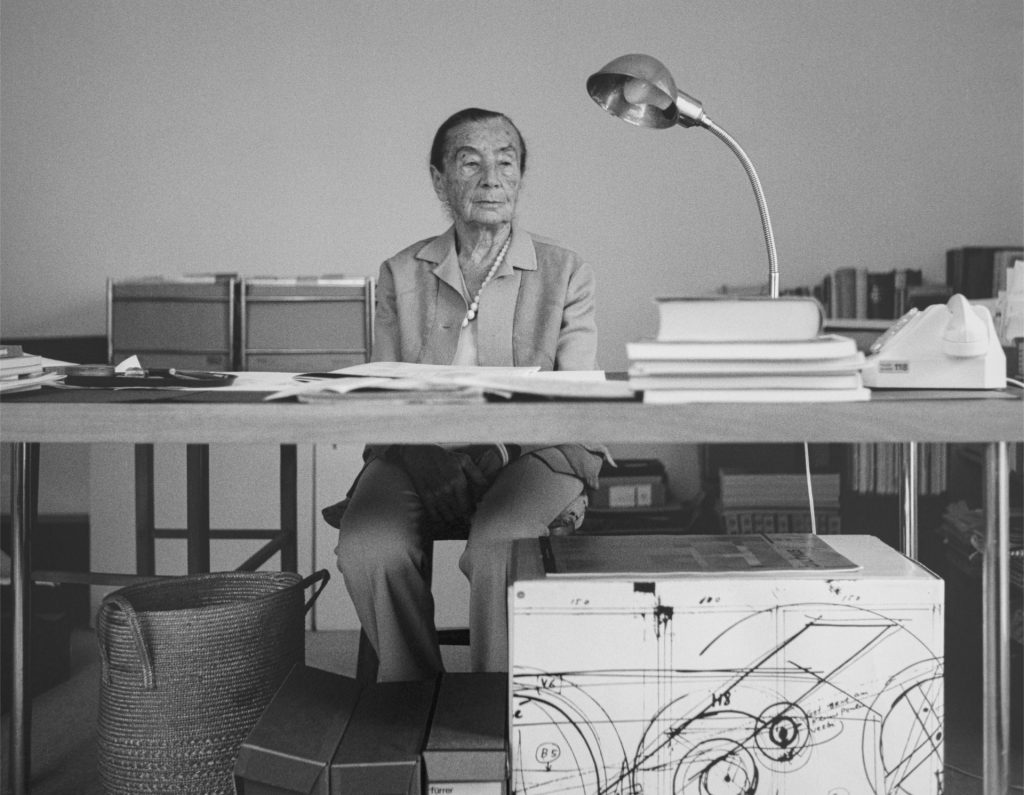

After the war, Moholy worked for Unesco as a “technical expert” and undertook ethnographic study trips to the Middle East. In later life she settled in Zurich, where she wrote for a variety of publications, including the Burlington Magazine, and was discovered by a new generation of academics and feminists.

“She really considered herself a writer, but used photography as a writing mechanism,” says Jordan Troeller, who co-curated the Prague exhibition with the writer Meghan Forbes and the Czech artist Jan Tichy (whose installation of glass prisms in the galleries delivers echoes of Moholy’s missing negatives).

Research for the Prague exhibition was hindered by the temporary closure of the Bauhaus Archive, which holds Moholy’s papers. Documents there might hold significance for some of the conclusions made here. It is an unfinished story.

“Actually, it’s always like that,” Troeller explains. “But in this case, that story is also the content of the show: being misrepresented or that facts are incorrect and have never been revised.” Rolls of film shot by Moholy lie undeveloped in the Bauhaus Archive.

Revision and correction are the leitmotifs of this remarkable survey. To some degree, Moholy achieved that in her own lifetime, winning a lengthy legal fight with Gropius for the partial return of her archive. But more than 300 negatives remain missing. One hopes that this exhibition will bring her talent fully into focus.

Lucia Moholy: Exposures is at Kunsthalle Praha until October 28, 2024