In its heyday, the Russian flag carrier – whose name means simply “air fleet” – flew some 400,000 passengers daily to an astonishing 3,500 destinations across the Soviet Union.

That was in the 1970s, when the “world’s biggest airline” could also boast a workforce whose numbers rivalled those of the NHS or Indian Railways.

Sadly for Aeroflot, the past 100 years have featured more nadirs than zeniths – most recently, the invasion of Ukraine has reduced a thriving member of Air France-KLM’s SkyTeam alliance to a fraction of its former size, struggling to keep its European and US-built fleet in the air by cannibalising spare parts from aircraft it no longer needs to fly. Most ignominiously, surplus crew face conscription to fight Putin’s war.

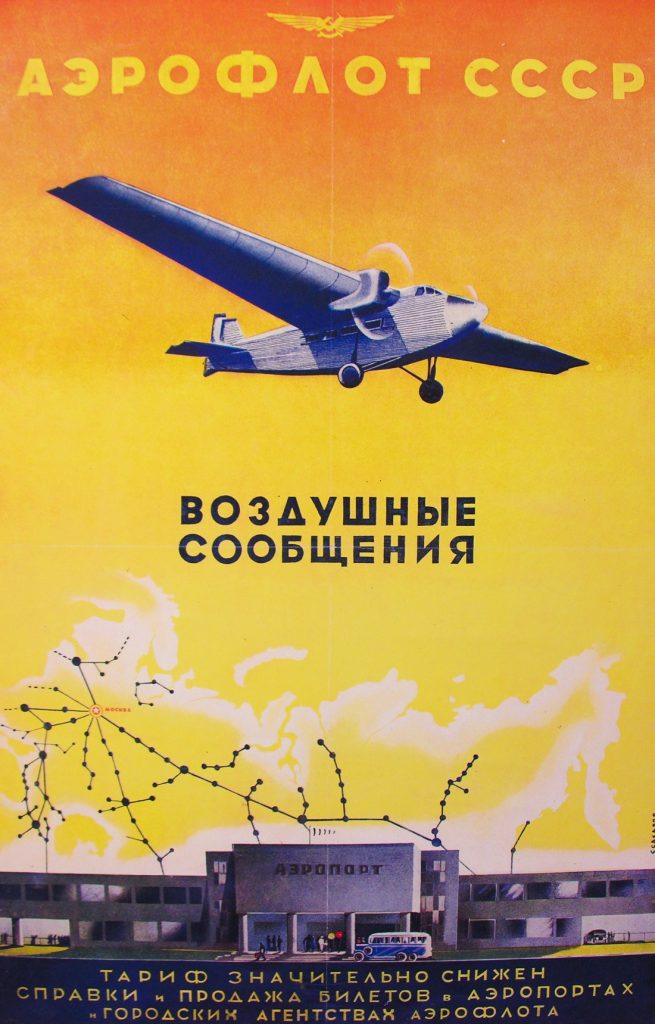

Up till then, Aeroflot had come a long way since Vladimir Lenin signed a document in 1921 setting out the Soviet Union’s aviation aspirations, leading to the foundation of the airline on February 3 1923.

The first scheduled flights began a month later and were operated by Dobrolyot, with the name Aeroflot only being adopted in 1932. This followed its merger with other airlines based in Tiflis and Kharkiv, transforming it into a pan-Soviet enterprise. The earliest flights were from Moscow to Kharkiv in Ukraine, via Oriol and Kursk, and then from Moscow to Königsburg in a joint venture with Germany.

By the time the second world war broke out, Aeroflot had become the primary link between Moscow and the various Soviet capitals, and government ambitions to reduce dependency on foreign-built aircraft were stimulating homegrown manufacture. When war ended, the Soviet Plan saw Aeroflot on course to quadruple in size, flying an all homegrown fleet. It did just about everything an airline could do, from ocean patrols and heavy equipment-lifting by helicopter, besides the mundane business of flying passengers.

In the airline’s “glory days” between the late-1950s and the fall of the Soviet Union, Aeroflot could claim main world firsts and world bests. I recall being awestruck on seeing a giant Tupolev Tu-114 on the ground at Le Bourget Airport, Paris, in the mid-60s. This monster had four huge turboprop engines turning eight propellers. Highly unusually for a propeller-driven plane, it had swept-back wings, enabling it to fly at more than 500mph – as fast as any jet airliner of the time.

It could carry 220 passengers more than 5,000 miles, but was anything but utilitarian inside: the “posh” version was more Dolce Vita than Domedodovo. The Soviet state had tuned in to the glamour associated with the rapid growth of air travel and saw aviation success as a potent symbol of national pride and achievement. So this refined iteration of the giant carried 50 fewer passengers but boasted restaurants, sleeping quarters and spacious galleys and loos, finished in shining chrome. When Nikita Khrushchev flew on one of the first machines direct from Moscow to the USA to meet President Eisenhower in 1959, crowds lined the runway at Edwards Air Force Base to witness not the arrival of a head of state, but of a giant of the skies.

When Aeroflot’s modest fleet of only 30 or so Tu-114s was retired after just 14 years in 1976, it was replaced by the Ilyushin Il-62 four-engined jet, which was larger and could fly further than its British or American rivals, the VC10, Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8.

When Aeroflot’s Tupolev Tu-144 “Concordski’’ followed Air France and British Airways into scheduled passenger supersonic service it did not face the same noise objections that restricted Concorde operations and for a time it whisked passengers the 2,000 miles from Moscow across the steppes to Almaty, in Soviet Kazakhstan, and nearly twice as far, to Khabarovsk, in Russia’s far east. But the aircraft, a prototype of which had crashed in controversial circumstances at the Paris Air Show, had only a limited commercial career, being retired in 1978 after just 103 scheduled flights for Aeroflot.

The fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s saw Aeroflot enter a bleak phase, with the creation of the so-called “babyflots” from the fragmented remnants of the airline across the Russian federation. Tales abounded of drunken passengers cramming the aisles of aircraft, and safety seemingly went out of the window while levels of personal service seemed to get even worse.

By 1994, Aeroflot – stripped of its home market – was left with just international routes and its fleet of more than 5,000 aircraft was heading down towards 100. But then the sale of nearly half the government’s shareholding to employees in 1994, and the consolidation of other state-owned operators back into Aeroflot, signalled the start of a revolution and a new era of achievement. This got off to the worst possible start, however, when an Airbus, en route from Moscow to Hong Kong, crashed killing all on board, after the captain allowed his 13-year-old daughter to take the controls.

Despite such setbacks, Aeroflot engaged British consultants to rebrand it, returned with vigour to the Russian domestic market and, in 2006, became the tenth member of SkyTeam, having contracted the American company, Sabre, to provide its reservations platform. This gave access to the industry’s Global Distribution System (GDS) enabling through-bookings on Aeroflot by all the world’s major airlines and agencies. In 2010 the airline finally banned alcohol sales in economy class on its “worst-behaved” routes.

Fast forward to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine: Airbus and Boeing withdrew technical support as part of international sanctions, meaning the airworthiness of the fleet was no longer recognised under aviation law in most countries, and Sabre shut off access to the GDS. Aeroflot’s international route network served only Minsk, though – as of now – it also flies to former Soviet republics in the Caspian area, as well as other countries, including China, Egypt, India, Iran, the UAE, Turkey, Indonesia, Thailand, the Maldives and the Seychelles.

It has been actively buying aircraft off-lease in an effort to circumvent the risk of seizure under sanctions rules, and most recently acquired 10 Boeing 777s from an Irish lessor for this purpose, or for further cannibalisation for spares. It has announced plans to order more than 300 Russian-built, mostly medium-range aircraft as part of a longer-term Russification programme, with echoes of the 1940s and ’50s.

The one great constant in Aeroflot’s topsy-turvy life has been its logo, created way back in the early Dobrolyot days: the famous winged hammer and sickle design even survived the Britishinspired makeover, which otherwise made Aeroflot’s livery suspiciously similar to that of British Airways.

You can see the old logo beneath the word “Aeroflot”, close to the badge for Skyteam, from which the airline is suspended – perhaps indefinitely