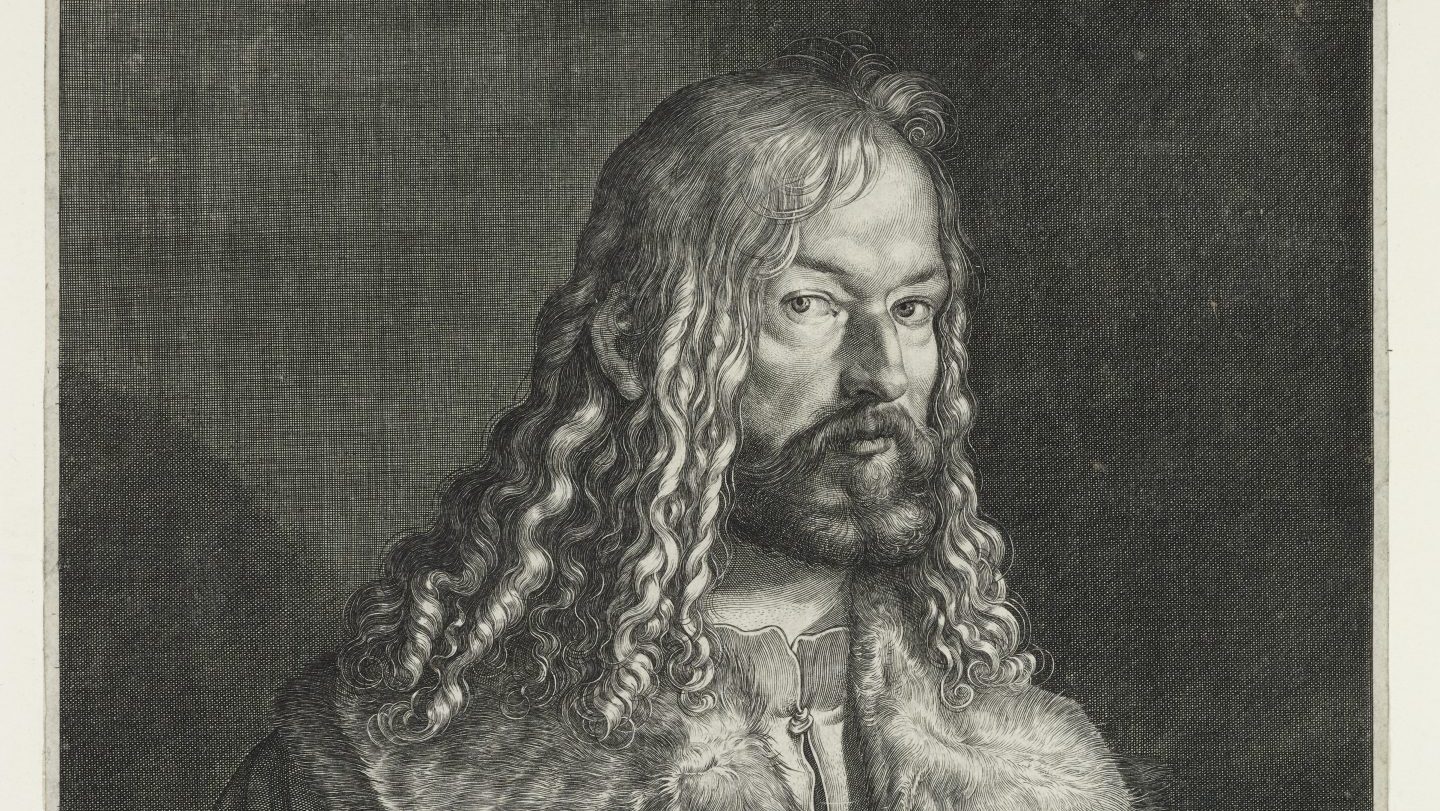

Albrecht Dürer was many things – printmaker, painter, traveller and theorist among them – but modest he was not.

While he did have moments of self-doubt, he was eager to raise his profile with self-portraits as a glamorous, Christ-like figure with flowing locks and a challenging gaze. He gave his works a distinctive AD monogram; very much a marketing device at a time – the turn of the 15th century – when these things were not common. “Here I am, these are my works,” it said.

In The Bath House (1496-7), Dürer gives himself a prominent position to emphasise how he mixes with humanists, musicians, men of culture and education. The scene, with its relaxing bathers, near-naked musicians and one boozer downing a flagon of ale, would also be a reminder to his neighbours that the communal baths in Nuremberg were closed in 1496 after an outbreak of syphilis. He naughtily has himself leaning against a protruding tap in such a way that it coincides with his midriff – or thereabouts.

This kind of panache and self-promotion and the fact that his prints, so demanding to make but so readily and profitably sold, made him a celebrity across Europe. “Why has God given me such magnificent talent?” he once asked, rhetorically. “It is a curse as well as a great blessing.”

Few artists encompassed the soaring spirit of the Renaissance with greater panache than Dürer. His paintings, etchings and engravings were born of a time when Italian humanism had reinvigorated the thinking of scholars and inspired the creativity of its artists.

A time too when the New World had been discovered in 1492, opening Europe’s eyes to exotic possibilities, and in 1520 Martin Luther had angrily denounced Roman Catholicism and sparked the Protestant Reformation.

The time, but also the place. When Dürer was born in 1471, his home city of Nuremberg had become one of the most important trading centres in Germany, its wealth based on the skills of its craftsmen and printmakers which reached new heights of ingenuity.

And it is that context and the effect the city and its artisans had on his work that is examined in Albrecht Dürer’s Material World (until March 10, 2024) at the Whitworth Gallery, Manchester, with an array of his meticulous, marvellous etchings and engravings.

Few exemplify that material world better than his 1514 engraving Melencolia I, which depicts a winged figure cast into a slough of desolation, gazing enigmatically into middle distance. In Dürer’s day, anyone suffering from melancholy was deemed most likely to suffer from insanity, though others argued that they were just as likely to become creative geniuses. Some experts suggest that the figure represents Dürer’s own philosophical and psychological struggles.

Surrounding the unhappy figure – it is unclear whether it is a man or a woman – are examples of work by local craftsmen and their tools, such as a saw, nails, an hourglass, a crucible and scales. A tiny sundial is a nod to the prolific production of the devices in Nuremberg that appeared on many buildings not just for telling the time but to proclaim that the city was in good order. In a reminder of the artist’s trade, a putto sits on a millstone with a slate and a burin, a steel blade ground obliquely to a sharp point which the engraver used to carve a design into the surface of a wooden block.

The figure is holding a compass which, with a ruler, was essential to Dürer’s quest to bring a system of proportion and measurements – almost a geometric calculation – to help him decipher the mystery of human beauty with perhaps its finest example, the engraving Adam and Eve (1504) in which he set the sinning couple alongside each other in symmetrical poses.

Just as Melencolia I tells us something about Dürer’s world, so too does Saint Jerome in his Study (1514) in which the saint, a popular Reformation figure depicted several times by Dürer, sits hunched over his desk, a halo glowing around his head. At his feet the lion from whose paw legend has it Jerome removed a thorn and turned the wild beast into a smiley pet.

Hanging from the wall are scissors, an hourglass, a rosary and the cardinal’s hat, while shafts of light stream in on what would be a typical home for a wealthy, educated Nuremberg family – heavy beams, wooden panelling, the deep window recesses and a chest. On his desk, a crucifix and an inkwell, and on a bench, comfy cushions and a few leather-bound volumes.

Many of these objects are brought to life in the exhibition, with objects ranging from rusty scissors blackened with time, to gorgeous silver gilt Apostle Spoons – each one has the image of an apostle on the handle and together they symbolise the Last Supper.

A sand clock, ravishing in silver, glass and silk thread, as glimpsed in Melencolia I, a brass bowl with the figures of Adam and Eve, and an exquisitely made brass astrolabe attest to the skills of the craftsmen, so too a silver apple cup, similar to the golden goblet brandished by the spirit of divine retribution in Nemesis (The Great Fortune). Just the kind of elegant artefact his goldsmith father would have made in his workshop.

A ceramic tile of a guardsman sleeping with halberd in hand is set alongside The Temptation of the Idler (1498), an engraving of a fellow dozing by a ceramic stove, the very acme of bourgeois luxury in Nuremberg.

Unaware of the naked temptress beside him, his head rests on two pillows and his fur-lined coat suggests that he is a man of some wealth able to afford such luxuries, but Dürer disapproved of such “perilous possessions” and once opined: “If a man devotes himself to art, much evil is avoided that happens otherwise if one is idle.” Perhaps that’s why the artist made the idler look so utterly gormless.

The brilliance of the artist can be confirmed (if need be) from a new set of impressions made to replace the long-lost copper plate of Melencolia I. Working back from the printing plate and using advanced scanning and 3D printing, the Swedish artists Goldin+Senneby have made 18 new versions – yours for £5,000 each – but despite the technological wizardry, the result falls short. Just compare the hundreds of finely scored lines etched by Dürer to create the clouds and sun’s rays with the 21st-century copy to understand why.

And if further proof were needed of his genius, a forgery of The Visitation based on the biblical tale of a pregnant Mary meeting her cousin Elisabeth made by one Marcantonio Raimondi in 1506 is hung side by side with the artist’s version. The fake is murky and dull while the original sets the emotional rendezvous of the two women against the backdrop of the Alps, whose grandeur is captured in minute, crystal-clear detail.

The comparison with imitators serves to emphasise the virtuosity of his works. The sheer complexity of Birth of the Virgin (1503), in which Saint Anne is in bed having just given birth to the Virgin Mary. Overhead, an angel swings an incense holder to mark the sanctity of the occasion, but Anne is not at the centre of the scene. Rather, Dürer is far more interested in the crowd of companions that surround her in what would have been a contemporary German bedchamber, with other mothers tending to their babies, gossiping, drinking from flagons and eating.

Similarly, while the subject of The Prodigal Son (1496) is the ragged figure of the penitential sinner kneeling abjectly among pigs – bristles as sharp as pins – the eye is drawn to the farm itself, which was described by Renaissance painter and art historian Giorgio Vasari as the “most beautiful huts, in the manner of German cottages”.

Though many of his works, like The Prodigal Son, reflect the immediate physical world around him, Dürer would be only too well aware of the wars, peasant revolts, religious quarrels and plague that dogged the end of the 15th century. Furthermore, as the year 1500 approached, doomsayers were forecasting the end of the world – a rather more serious version of the Millennium Bug, 500 years earlier.

Dürer’s reaction was to create the breathtaking Apocalypse cycle of 15 woodcuts including The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Death, Famine, War and the Conqueror who gallop thunderously across the print with an eye-popping fury. The Conqueror brandishing a crossbow like one on show in the exhibition and quite possibly made in Nuremberg. Sinners, whether children, soldiers or emperors, are mown down, a bishop is trampled under hoof by Death and is eaten by a macabre creature. No one will be spared on the Day of Judgment.

By contrast and easily overlooked because it is so small, a mere 11.4cm by 7.1cm, is Virgin and Child on a Grassy Bank. She gazes at the infant, full of love, holding him tenderly in a tranquil, enclosed garden – a reference perhaps to her virginity. It is an enchanting scene, less to do with Dürer’s material world than his spiritual and the embodiment of his instinct that “simplicity is the greatest adornment of art”. Even to an immodest man with little to be modest about, it absolutely is.

Albrecht Dürer’s Material World is at the Whitworth, Manchester, until March 10, 2024