When my washing machine broke last week, I found myself scouring Facebook groups for expats in Athens in search of a secondhand replacement. I was scrolling through the message boards when one stopped me in my tracks.

“Sorry for posting anonymous but it’s a bit private,” it read. “I am a foreign female and received the online insult and death threat of killing me from a Greek stranger man after keeping refusing his requirements of being his gf. I only know his full name and have the chat history. Anyone know the procedure of applying restrictions etc in Greece?”

The replies were sympathetic, but not particularly hopeful about how helpful the police would be. “You won’t get anywhere,” read one response. “If anything, you will be asked what you did to provoke him. Greece is not a safe place for women.”

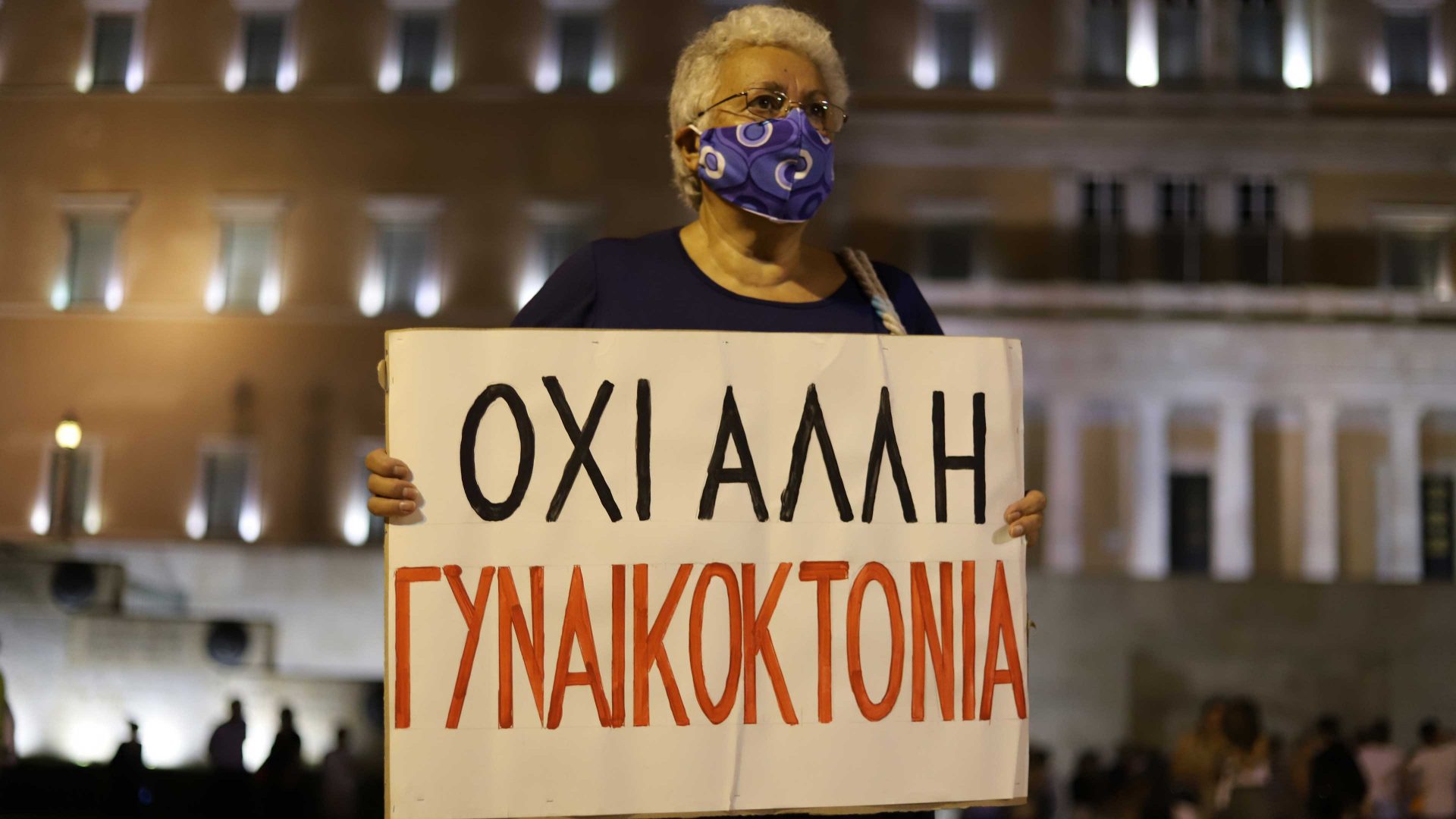

It’s an understandable view, given recent events. Earlier this month, a 29-year-old woman named Kyriaki Griva was fatally stabbed by her ex-boyfriend outside the police station where she had just requested protection. It was the sixth femicide in Greece this year.

Back in January, the murder of a pregnant woman in Thessaloniki by her partner and his friend sent shockwaves across the country and sparked fresh cries for the term “femicide” to be legally recognised. “We’ve been calling for this since the horrific murder of Eleni Topaloudi back in 2018,” said Emmanouela Soldatou, from the Greek charity Genderhood. Topaloudi was a 21-year-old student who was brutally raped and killed by two men on Rhodes after refusing their sexual advances.

Like many Greeks, Soldatou believes in the importance of creating a distinct legal label for homicides of this nature. “In order to prevent a social phenomenon, you need to define it. Prevention strategies can only be properly conceived if the crime is properly defined.”

Greece isn’t exactly out of step with its European neighbours when it comes to legally defining femicide. In the EU, only Cyprus and Malta recognise it as a crime in its own right. But for Soldatou, solving the issue involves more than just the introduction of a proper legal definition. “These murders do not come out of the blue. They have distinct foundations in our patriarchal society. We need to address misogyny at its root, that’s why at Genderhood we go into schools and run workshops with the children.”

The biggest concern after a murder like Griva’s is that it will discourage victims of gender-based violence from coming forward. “She was literally right outside a police station and still she had no protection,” a friend told me. “Here in Greece we don’t trust the police, we fear them. We feel like they’re here to threaten us, not protect us. Police phobia is a real thing.”

A recently released report from the policy institute Public Issue backs up her view. The report revealed that 70% of Greeks don’t trust the country’s justice system. That’s up from roughly 30% in 2018. “It got so much worse with Covid,” she told me. “We had really strict lockdowns here and there were so many policemen aggressively patrolling the streets, threatening us.”

The Greek police force has a long history of corruption and excessive use of violence, but since the election of New Democracy in 2019, complaints against them have soared. Prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’s centre-right party ran, at least in part, on a law-and-order platform and has since poured public funds into hiring and training thousands of new officers, while also expanding their powers.

In recent protests following a deadly train crash, police were accused of using excessive force during peaceful rallies, with several videos exposing the brutality. They have also been accused of violently intimidating journalists covering the refugee crisis.

Given this track record, many weren’t surprised by Griva’s death. “Of course we were angry and disappointed,” my friend said. “But there’s also a sense that, given the current state of our police force, these kinds of events are inevitable. And that’s really tragic.”

Hester Underhill is a freelance British journalist currently based in Athens