The artist James Ensor (1860-1949) became a familiar figure in his later years, strolling along the promenade of his home town, the Belgian resort of Ostend, with his two tiny dogs, resplendent in smart black hat and long yellow overcoat. He would often pause before his bust, erected by an admiring city in a nearby park, and doff his hat.

Was it the gesture of the supreme egotist who as a young man of 19 had failed his course at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels yet had the confidence to brag: “I believe I am an exceptional painter”?

Or was it an ironic signal of contempt aimed at his many critics whom he described as “cowards crushed by my disdainful progress”?

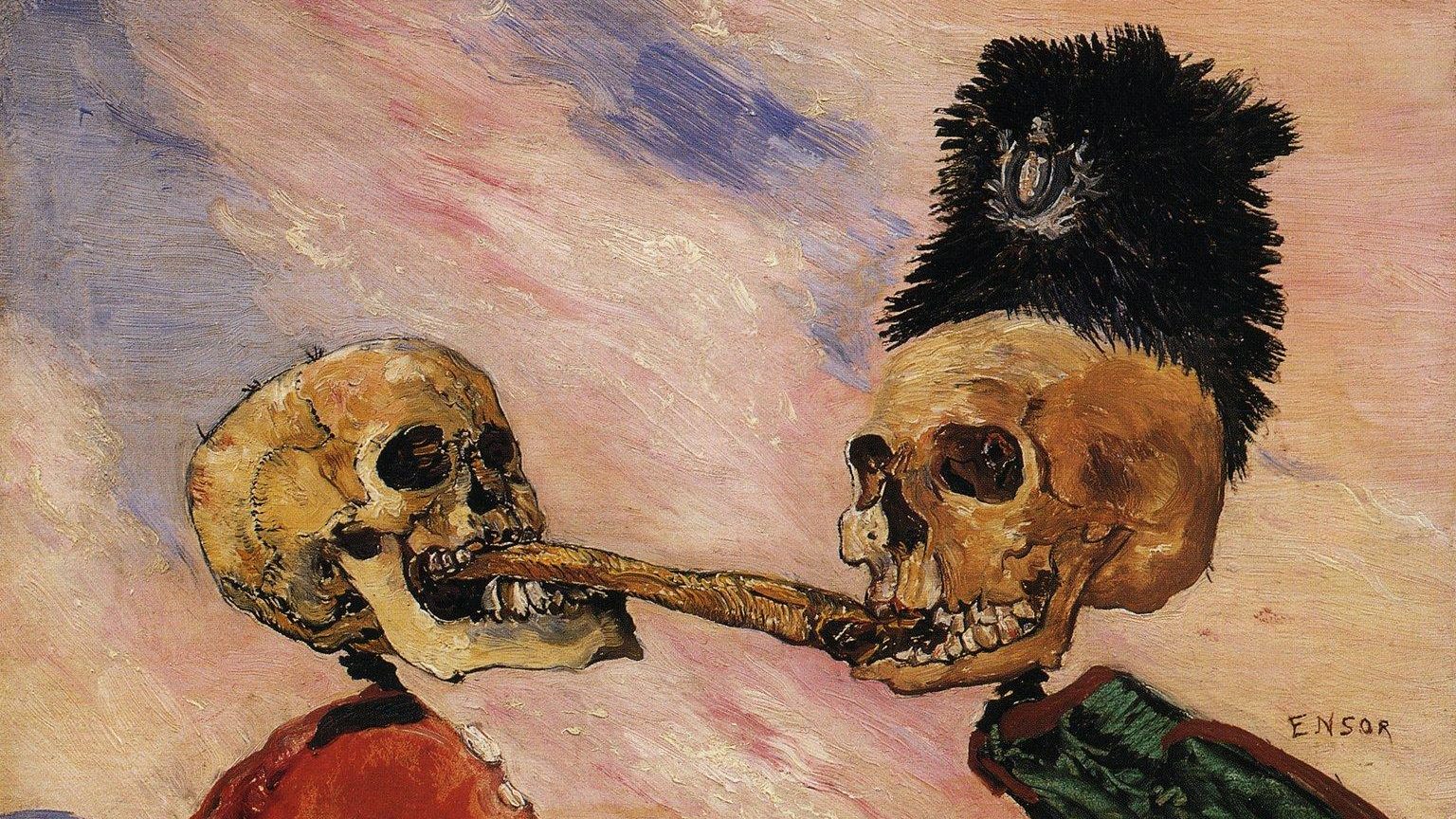

He had savaged his detractors in Skeletons Fighting Over a Pickled Herring, in which he represented himself as a hapless fish caught between the remorseless jaws of two skulls, a scene typical of his charivari of the grotesque that he is best known for. His characters in gaudy carnival masks, shrieking with crazed abandon, mocking, jeering, leering, his skeletal figures, ominously portending the inevitable in a universe of contradictions and confusion in which nothing is quite what it seems.

But as a year of celebrations to mark the 75th anniversary of the artist’s death demonstrates, with exhibitions in the Flanders cities of Ostend, Brussels and Antwerp, there is more, much more to admire. And to puzzle over.

The Ensor trail begins in Ostend in 1860 and ends there with his death in 1949, when he had won international fame and been made a baron, no less. He lived with his parents, and later his sister and grandmother, above one of the seven shops the family owned, where they sold seashells, dolls and Chinoiserie vases to holidaymakers.

The greatest demand was for carnival masks and cloaks, bright and cheerful, and for skulls, grisly remains, some of which had been found in the nearby dunes where Spanish soldiers had perished in a bloody encounter in the early 17th century.

His father died of alcoholism when Ensor was 17 but he had recognised his son’s artistic talents and encouraged him to attend the Academy in Brussels. On his return to Ostend, he took over a tiny room on the top floor above the family flat and there he worked for 37 years seemingly indifferent to its claustrophobic low roof and poor lighting, its walls lined with paintings, leaving barely enough room for the impedimenta of his trade.

In 1915, after the death of his mother, Ensor moved across the street and round the corner to another of the family emporia, locked the front door and shut up shop.

One might expect Ostend’s Mu.ZEE gallery, with its collection of Belgian art, to feature Ensor on a grand scale but in fact it has only a handful of

his works – including a touching painting of his mother on her deathbed – so his new home, the Ensor House, is the main attraction

for those wanting to fathom this complex character.

The shelves of the shop are still lined with the same shells, hideous masks and skulls which had proved such a pull to souvenir hunters and, similarly unchanged, the gloomy studio-cum-living room with its heavy brown furniture and harmonium which he played badly but indefatigably, composing music for a ballet.

On one wall, a reproduction of his tumultuous masterpiece Christ’s Entry into Brussels (1889) which he had painted in his old attic studio. It was so huge – more than eight feet high and 14 wide – he was compelled to paint it section by section, strip by strip, and had been unable to unroll it, let alone display it until the move.

An interpretation of the work, curated by Ensor expert Xavier Tricot, has just opened, including publications and details from the painting, as well as a tapestry version of it made in 2008 after the original was sold to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

It does much to enhance understanding of a painting in which Ensor created a carnival scene with scores of laughing, sneering, clamouring faces railing against the clergy, the military and the politicians, anyone in authority, all milling around the tiny figure of Christ who looks uncannily like the artist himself.

Being the contrarian he was, he included two figures on a balcony, one of whom is vomiting and the other defecating on to a green banner which bears the letters XX, the name of the collective he had helped found in 1883.

Unsurprisingly, this insult led to the work being rejected by his erstwhile comrades and Ensor, once again, bemoaned that the critics had treated him with a “viciousness beyond all known limits.”

It was typical of the man: angry, vindictive and solitary. A judgment given credence by his artist and friend Léon Spilliaert who wrote that he “lives a sad and lonely life… vegetating in this ruined and ransacked town” but one disputed by Ensor enthusiasts who insist he had plenty of friends, enjoyed frequent visits to Brussels, and even had a ladyfriend living across the street.

So what was he like? An exhibition of the artist’s self-portraits in the Ensor House arranged by Tricot offered an insight into his complex character. In what is perhaps the best known, Ensor looks sideways at the easel, like a “valiant Spaniard”, as one admirer described him: “tall, with dark curls, a pale skin, a piercing glare, moustache in the wind”.

But what gives him a distinctly raffish air is the hat, decorated with flowers and sporting a feather that wafts down to his shoulders.

He seems confident enough but Tricot argues that there are signs of vulnerability. “It is as if he is asking ‘what am I doing here?’. He is so certain of his own capacity in one way but in the other way he is searching for his own identity. ‘Who am I? What am I doing in this society?’”

One series of images explains much about his sense of identity. A photograph shows him at ease, one hand in the pocket of his suit, the other arm resting on a windowsill. He is looking rather shiftily – or is that embarrassment – at the camera.

Ensor takes over with an etching. He has the same expression, though the pose is reversed. Then the face begins to disintegrate into the outline of a skull until in the third drawing it is a skeleton standing there

“He thought the original was too classic,” says Tricot. “He wanted to exhibit himself to the world and recognise that we are all the living dead, living skeletons, and that death is something we have to face.

“Of course, he is using his obsessions and frustrations like all others, but first of all he is a painter. He is a creator. Don’t lose that.”

Herwig Todts, who is curator of In Your Wildest Dreams. Ensor Beyond Impressionism, due to open in September at Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA), would agree.

“The fact is he was trying to invent something new. He was asking himself: ‘how can we make art which is not like a photograph?’ Why not try something else like many late 19th-century artists – shed the strictures of realism and turn art into something more free and more expressive just as Gauguin, Odilon Redon, Van Gogh, Edvard Munch and others did.”

Given that Ensor was surrounded by masks all his life it is hardly surprising that he should use them in his quest for the new. He was attracted by their colours and by their expressions and declared that they meant “freshness of colour, sumptuous decoration, wild unexpected gestures, very shrill expressions, exquisite turbulence.”

All that is exemplified in Intrigue (1890) which captures the peculiarly abrasive spirit of Ostend’s carnivals with a throng of masked figures with piggy faces, gaping red gashes for mouths contorted in loathing.

A woman holds what looks like a dead baby on her shoulder while the couple in the middle seem to be menaced by the others. It is an ugly scene but what are we to make of the people behind the masks?

Todts says: “They are caricatures and when they look stupid it’s not because they pretend to be stupid, no, it’s because the people behind the mask really are stupid, ugly, laughable. They are a sort of image of humanity. This is what we are. This is like a mirror.”

Anger, ugliness, the grotesque. Typical Ensor. But not altogether. Who would imagine that the man who painted Intrigue and Christ’s Entry into Brussels also painted pretty still lives of flowers in Chinoiserie vases and tables of fruit and vegetables?

In yet another contrast; Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise (1887) is a dramatic explosion of light and colour depicting the shamed couple as tiny naked figures, almost lost in Ensor’s barrage of colour. Similarly, The Fall of the Rebel Angels (1889) with its great swirls of paint conjure up a fury of retribution and suffering.

If these are wildly expressive, The Oyster Eater (1882) is a quiet representation of a woman at a table eating an oyster by herself. From across a crowded gallery its rich, subtle colours, the light catching the oyster and glancing off the bottle of wine, it could quite easily be by Manet. An effect he had been determined to achieve.

“There was no development from one style to another,” insists Todts, whose book Occasional Modernist examines Ensor’s own writings. “He does this, then he does that, moving from one artistic project to another. It was all done on purpose.”

And Todts makes the point by comparing placid scenes of ships in Ostend Harbour with the hurly-burly of Intrigue, both painted in 1890.

As Ensor himself wrote to an art critic: “The artist must invent his style, and each new work demands its own.”

Full details of the Ensor 75 celebrations at visitflanders.com/en/james-ensor-flanders