It was the subtle weaving of it all that made me watch the coronation. Twice.

What was Charles Philip Arthur George saying?

While it was unfolding, while all of the stuff was going on, it was easy and convenient to be wrapped up in the narrative. Narrative was all, and so was spectacle. Someone interviewed after it was all over remarked that it was quite incredible to see this enthronement. To see it all in colour.

The last coronation, in another world and in another time, had been like some kind of dream. It was, after all, a dream to most people, something before their time, something in another time. Where are the people now who had seen it, who had been in the crowds, who had eaten the coronation chicken and lived in the coronation streets? How many could now say that they were adults who had sat at the long tables in the road, toasting the young Queen?

Those who can answer these questions are now peripheral to us, old people from an old time. And the black and white coronation, briefly in colour, belonged to them. Was meant for them. Not us.

This coronation of the third king known as Charles belongs to us. To our time, our age. We pick over the entrails of it with our devices and maybe even pretend that nothing like it had ever occurred.

At one level, this would be correct. Because Charles was weaving his own design and this weaving happened on many levels:

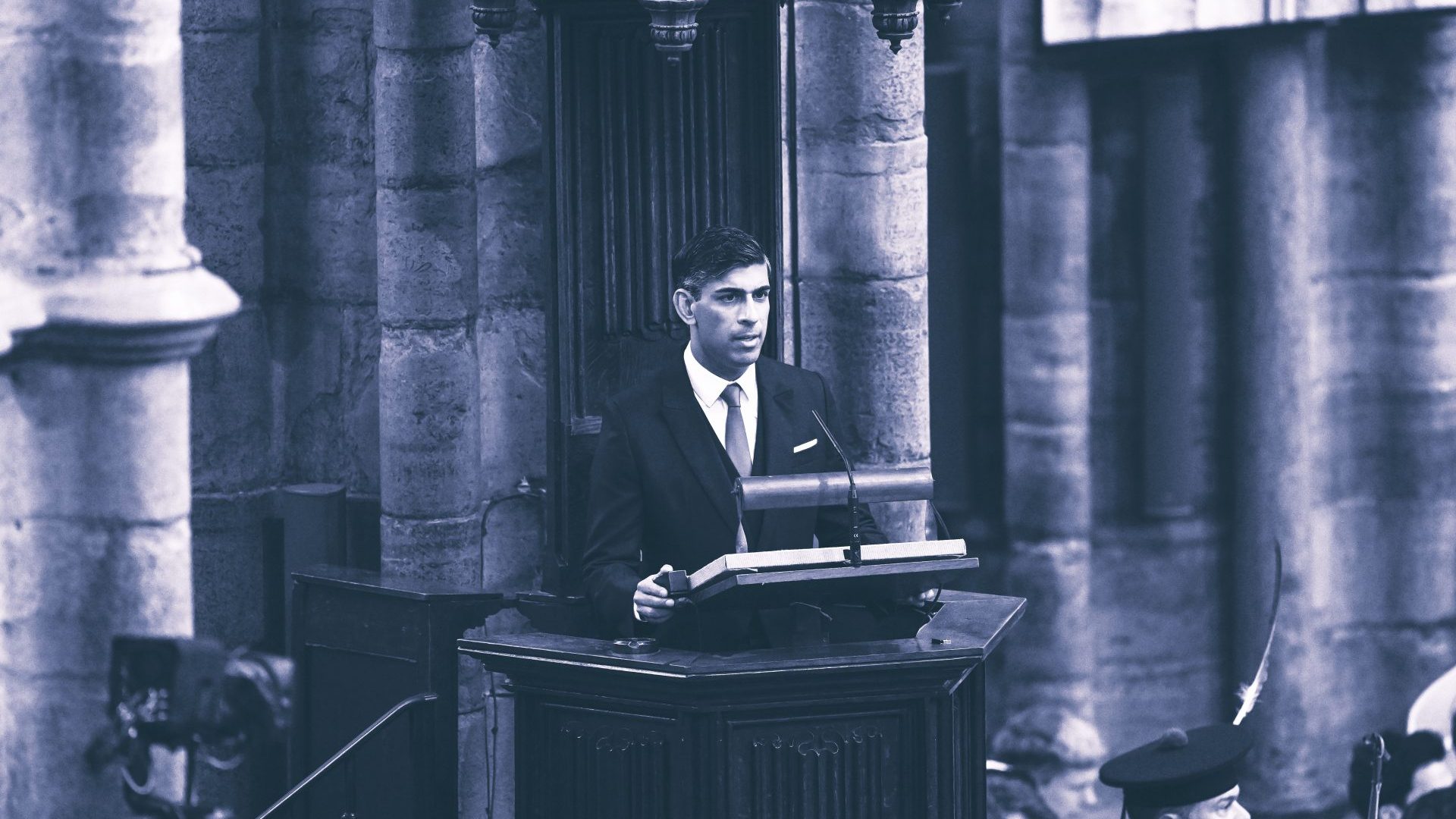

The first woman to carry the sword, leading the King in, preceded him. Two women of African descent, Black British, bore the sceptre and orb. The “Kyrie” was sung in Welsh, the first time this language has ever been spoken or sung at a coronation in Westminster Abbey. There was the prime minister, a devout Hindu, reading the gospel with all the conviction of a Church of England cleric on a Sunday morning. Music from the Greek Orthodox church in honour of the new King’s late father, a prince of Greece. The heir to the throne planting a tender kiss on the cheek of his father, the new King’s cheek. And even as the people in the Abbey paid homage, the new King showed us constantly a vulnerable human being, caught up in history.

This is how a dramatist sees it; a maker of fiction; someone foreign-born. Foreign to the reality of this privileged family, privileged from birth unto death and beyond. Their land; their sovereign grant; their tax status, all of it faded for a few moments for most, I suspect, as the events in the Abbey unfolded. “You straightened yourself up,” as they say in the States, for the events in the Abbey. Even the wife of the president of the French Republic pulled herself up as she walked with her husband through a long gallery, on their way to something more spectacular in itself than Versailles with its hall of mirrors.

Before dawn on the morning of the coronation, I walked down the Mall and through Green Park to the broadcasting tents. I was commenting for CNN and, in New York City, it was mid-evening, time for a hunker down after dinner.

I wanted to say to those New Yorkers, in the time allotted to me, that there were people around me, out there in the dark. Up and down the Mall there were clusters of people, hunkered down in their sleeping bags; under their blankets and their coats; the lights strung up on the barrier fences providing enough illumination for them to see one another in the dark. That early morning, sitting outside of a broadcasting tent with Buckingham Palace behind me, I thought about those on the Mall. And how young many of them were.

One of the people working with us guests for CNN told me that she looked along the Mall for “my Kiwis”. And they were there, proud and happy to be there. They, too, were part of the subtle weaving, woven by the presence of the new king.

Someone tweeted to me asking what I thought of the “illegal arrests”. He was referring to the protesters demanding a Republic. At two in the morning, moving along the road to the broadcast tents, looking up from time to time at the fuzzy full moon shining behind the palace, it was hard to imagine a demonstration against the new King. Not because he should not be demonstrated against; not that it wasn’t something many people wanted – the abolition of the monarchy – but because that subtle weaving which is the British monarchy was clearly dominant on the day. By custom, by design, say what you will. But it was there. And it ruled.

But the nations of the Commonwealth will gradually unlink themselves from a monarch.

I can still see Charles’s subtle smile as Barbados announced at a ceremony, to his face, that he was done. That their new queen was Rihanna. Rihanna sat there in her power and her glory and it all made sense, even, it seemed to me, to Charles himself. As if he understood the joke that his position was, that he was, as he sat on a chair in a nation across the ocean which had called him their head of state. No “Vivat Rex Carolus” here.

That is Barbados. But continuity is a high value in the UK. The maintenance of continuity explains a great deal, too, and Charles was careful with it. When asked if he was Protestant by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Charles answered that he indeed was. When asked if he would maintain the Church of England, he answered in the affirmative to that, too. The crowd that I saw that dark early morning on the Mall would have no problem with his answers.

Yet it would be easy to imagine, easy to see a different world. The eldest grandson of the King helped carry his train, a sombre-faced little boy, his mouth twitching as he stood among the child choir after his work was done. He looked as if he felt out of place. Was out of place. Prince George is the future king if all goes as it has always gone.

Yet, as weaver of his coronation ceremony, Charles could be demonstrating that his grandson may not inherit a kingdom. May not walk down the central aisle of the Abbey to that pavilion, the traditional space where the sovereign is anointed, out of sight.

He, a champion of continuity, and of discontinuity, may be saying to us that he is the last. The last sovereign.