For years, the Alexander Column in St Petersburg symbolised the might of Tsarist rule. Built to celebrate Alexander I’s defeat of Napoleon in 1812, it towers above the vast Palace Square and the Winter Palace, once the grandiose home of the royal family.

How the crowds must have rejoiced when they gathered in October 1918 to celebrate the first anniversary of the Bolsheviks’ overthrow of the Tsar, to find that the square and its palaces were bedecked with 50,000 feet of abstract decorations, while a tremendous construction, all hard edges and cubist planes, surrounded the column with a “blaze of yellow, reds and orange like a quirky, colourful firework”.

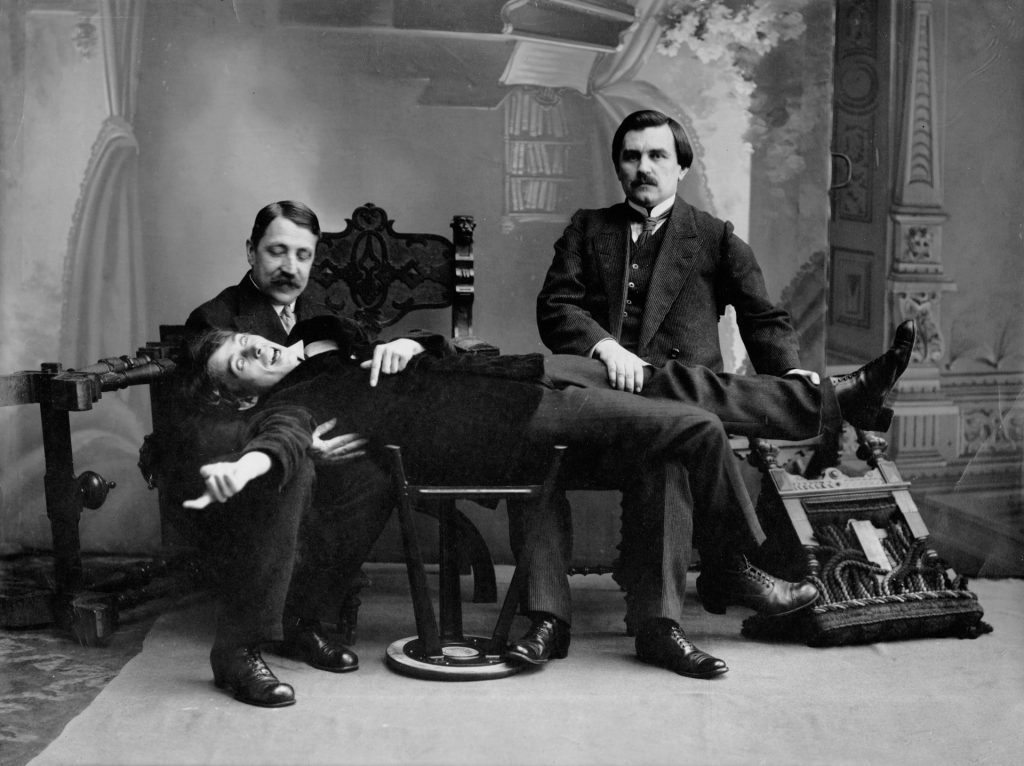

For the artists who had perpetrated such a cheerful outrage, it must have felt as if they and the Bolshevik leader, Lenin, shared a similar vision, inspired by the “joyous light of freedom”. It was the moment when a bunch of “brilliant, talented crackpots, libertines and hardworking gadabouts” could not only freely express themselves with ground-breaking art, but also be confident they would play an important part in shaping the cultural and social institutions of the nascent Soviet Union.

Their extraordinary story is told in The Avant-Gardists: Artists in Revolt in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union 1917-1935 by Sjeng Scheijen, in which he salutes the blazing talents of the artists while describing how they blighted their own bold intentions with pettiness and bickering. And how they were, in time, undermined by the apparatchiks, toadies and ideologues of the Marxist regime.

It’s a story told against years of civil war and violence that accompanied the early years of Bolshevik rule, and the pogroms and savage repression, famine and hardship that followed. It ends – for people and artists alike – in the “stifling morass of Stalinism”.

The heroes of the book – those brilliant crackpots – are among some of the most influential artists of the last century; Marc Chagall, Wassily Kandinsky, Lyubov Popova, Alexander Rodchenko and Olga Rozanova, all “proletarians of the brush”, as Rodchenko described them. They were happy to see the “toppling of the monarchist throne” but, as Scheijen emphasises, while their art was revolutionary they were not players in the revolution itself.

What he celebrates in the book, and illustrates with several striking images, is the “inflated, magnified, distorted, terrifying humanity (of the artists) that makes their work so provocative, and at the same time so astounding, compelling and moving.”

Few were more compelling than Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin. Both broke the rules and altered perceptions, but were always rivals artistically and often bitter foes when it came to what they considered to be their rightful place in Russia’s new cultural hierarchy.

Malevich (1878-1935) was influenced by symbolism, cubism and Russian folk art, as his muscular paintings The Woodcutter (1912) and The Knife Grinder (1912-13) illustrate, but found his true voice when he “sought refuge in the form of the square”.

At an exhibition in St Petersburg in 1915, which he called 0.10 The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting, he presented his Black Square, a simple, geometric, shape – “the most radically abstract painting known to have been created so far”. He followed it with Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918), which was quite simply an off-white square on a similarly coloured background.

He argued that his fellow avant-gardists should “burn the road behind us” by adopting pure abstraction, shunning natural shapes and forms and instead embracing “the primacy of pure feeling” expressed in circles, squares and crosses. He called it suprematism.

Contemporary critic Nikolai Punin wrote: “Suprematism is the focal point, the centre where all of the world’s art converges to die”, and he added that Malevich’s students “deified him like Napoleon’s army”.

But not all. Tatlin (1885-1953) had followers just as passionate. “We needed Tatlin like we needed bread,” exclaimed one admirer.

He had worked as a merchant seaman, a busker and a circus wrestler, but became leader of the constructivist movement, hanging sculptures or “painted reliefs” such as Corner Counter-Relief (1914) made of sheets of iron, copper and wood strung from walls with cable. His most famous work, the design for the Monument to the Third International was, in effect, an abstract building with a leaning spiral iron framework supporting a cylinder, a cone and a cube, all in glass, which could be rotated at different speeds.

At 1,300ft it was part of Lenin’s Plan for Monumental Propaganda, a symbol of the new regime’s technical achievements. But the tower never rose beyond its 22ft model, and two years later, in 1922, it was perceived as an embarrassing reminder of futurist artists and their “imbecilic, deformed monstrosities”, broken up and used for firewood.

“The traditional barrier between painting and sculpture had been torn down,” writes Scheijen. “Suddenly, any materials proved suitable for making art. Painting, which had occupied the topmost position in the hierarchy of fine arts since the Renaissance, thus tumbled from its pedestal.”

The avant-gardists were seized by the desire to “send out the express trains of new artistic achievements,” and it was to that end that Tatlin agreed to join a collective in which the cultural masters of the new era would gather. Malevich was too grand to collaborate in such a project.

Called Café Pittoresk, it was owned by a philanthropic pastry chef and decorated with sculptures of figures and random shapes. As well as the serious-minded like Tatlin, it had its eccentric regulars; a yoga teacher who would split wooden boards in two with his forehead and the performer of “word sculptures” who would dance on the club tables “occasionally even leaving her clothes on”.

Tatlin soon fell out with the owners and was asked to be the head of the Moscow art division’s new People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment, a role that made him the most powerful cultural minister in the capital, though only for a short while.

The years immediately after the revolution were characterised by shortlived bureaucratic institutions designed to formalise the role of the arts in the new Soviet Union. They were invariably blighted by furious disagreements such as the ones that erupted in the Department of Fine Arts, which Tatlin headed in Moscow and Malevich in St Petersburg.

Both men were dismissed after a meeting which Kandinsky described as resembling “a stock exchange more than a business meeting. There was commotion, hubbub, shouting and swearing”.

Rodchenko’s partner, Varvara Stepanova, said: “The two generals fought each other to the death.”

Malevich left the hot house of St Petersburg in 1919 and travelled 300 miles to Vitebsk, where he took on a job as a teacher with, among others, Chagall. This was a productive time for him, creating a system of education and launching a movement, the Champions of New Art, in which he aimed to establish a “collective creativity” rather than indulge individual artistic expression. It was enthusiastically received by students, who wore black squares on their lapels.

But the freedom Malevich enjoyed in Vitebsk was under threat, as it was across the country. The civil war that broke out between the Tsarist (Whites) and the Bolsheviks (Reds) in 1918 had cost millions of lives, and in 1921, alarmed by threats of civil unrest, Lenin ordered a clampdown on political freedom.

So many artists and thinkers were deported that the ship that took them away was dubbed the “philosophers’ steamboat”.

In 1922 Malevich left Vitebsk for St Petersburg, where Tatlin had joined the city’s Museum for Artistic Culture. There he concentrated on “material culture”, which included somewhat whimsical projects such as designing a stove and a hat, and even a set of crockery for children.

Malevich became the museum’s manager and reorganised the place, reducing Tatlin, who lived there, to rampant paranoia. He shut his windows in case the “villain” Malevich spied on his work, he put seven locks on his studio and made a peephole so he could check who was at the door.

This clash of egos, the unceasing wrangles over the ideological role of art in society meant that the avant-gardists were bound to lose out to the increasing pressure by Lenin and the Bolshevik hierarchy for art that reflected the glories of the Soviet system with figurative scenes of honest toil and patriotic fervour.

That became painfully clear at exhibitions to celebrate 15 years of Soviet art in 1932-33. Their work was corralled into corners of the hall and overshadowed by a huge printed quote by Lenin: “I am unable to see works of expressionism, futurism, cubism, and other ‘isms’ as the greatest manifestation of artistic genius. I do not understand them. They give me no joy whatsoever.”

As Scheijen writes: “This single quote from the father of the revolution… worked its magic like a medieval curse.”

Of the few remaining avant-gardists, the majority accepted that they had been defeated by the “morass of Stalinism” and many of Malevich’s old comrades left the country, while he settled for minor commissions including “a rather pitiful landscape”.

He died in Moscow on May 15, 1935, aged 56, and was laid in a coffin decorated with a black square and a circle. A tearful Tatlin walked up to Malevich’s body, studied him carefully, and said: “He’s just pretending.”

The Avant-Gardists: Artists in Revolt in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union 1917–1935 by Sjeng Scheijen, Thames & Hudson, £35 hardback