Here’s one for the home secretary; a small boat. Tiny. Made of bronze, not even 21cm long. It was made by Sardinian craftsmen more than 3,000 years ago and is the first object to greet the visitor in a fascinating, quietly subversive new exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

Islanders: The Making of the Mediterranean is a fabulous collection of antiquities – more than 200, and many never seen in this country before – from the islands of Cyprus, Crete and Sardinia. It aims to show how the evolution of the Mediterranean world was defined by cultural exchanges, trade, war and immigration across three millennia.

Take the boat, which was made sometime between 1000 and 700BC. It has a central mast that represents the extraordinary megalithic stone towers called nuraghi, in which the Sardinians lived for centuries until Roman colonisation in 238BC.

All that is known about this civilisation has been gleaned from its ancient burial grounds, which have yielded unique bronze figurines, including the boat with its carved birds perched on a lattice-work hull, and a prow in the form of a graceful long-horned bull.

Nowhere else in the Mediterranean are there buildings like the nuraghi, which might suggest that the island was unconnected to the others. Yet Sardinia almost certainly imported the bronze of which the boat is made from Cyprus, and it is quite possible the metal was dug from the Cypriot mountains by immigrants from Anatolia – ancient Turkey. That small boat shows that a country and a culture can preserve its identity without turning its back on the rest of the world.

It earns its place in the exhibition for its finely wrought craftsmanship, but the boat – and the show – are really about Brexit. It stands as a challenge to the egregious claim by Michael Gove in 2016 that 77 million Turkish citizens could be knocking at our door demanding access. It is a riposte to the home secretary, Suella Braverman, who announced – wildly – that 100 million refugees were about to sail the Channel in small boats and invade the UK.

The genesis of the show begins with that glum day in 2016 when the country voted to leave the EU. But the issues raised – the xenophobia, the dog whistles, the intolerance – go back further to at least the 1960s, when a group of French academics argued in their journal Les Annales for the need to examine cultures chronologically and relate the ancient world to the modern.

As the show’s chief curator, Anastasia Christophilopoulou, explains: “This was born out of the Brexit referendum. A number of us were quite angry.” She laughs wryly. “It felt like a challenge to our own identity. We thought about who we are here in this country, economically, academically and socially, and asked ‘how does this country think differently in relation to central Europe in terms of cultural ideas and phenomena?’ We decided to investigate whether there would be a case to compare what was going on in the Mediterranean centuries ago with today.”

Spurred on by the “Get Brexit Done” election of 2019, a group of geologists, sociologists and experts in antiquity in the UK began to give talks, show films and contemporary art shows to highlight how history tends to be identified in closely defined eras. Historians often refer to epochs and places as, for example, the Peloponnesian war, the Mycenaean civilisation, the Greek and Roman empires. The effect is to give an impression that these eras are unrelated to what came before or after – that they are not part of a historical or cultural continuum.

The exhibition is only one of the group’s weapons. Every object on display tells a story about the way the islanders lived, fought, celebrated the gods, fed themselves and died. In telling these stories, the show highlights the movement of people, including those from Anatolia centuries ago, and in doing so, it foreshadows the migration crisis of recent years, especially the flight of refugees from Syria.

It also explains how, like the sturdily independent Sardinians, they were prepared to trade and share their knowledge without fretting about losing control of their individualism.

Many of the artefacts are freighted with emotion, and poignant for being so small – like the clay figure of a woman, from about 9000BC, giving birth supported by a partner whose legs are wrapped around her waist, arms around her chest.

What the curator refers to somewhat ungallantly as the “fat mother” is a rounded limestone figure who would have been buried more than 7,000 years ago with pottery vessels, bone tools and necklaces of minute shells.

Along with the figurine of a mother goddess from Sardinia made of marble, with its curiously flat head and angular body, they suggest that the islands were once a matriarchal society.

A mother mourning the death of her son in battle holds up a hand in prayer while she laments his passing. It was cast in bronze between 1000 and 700BC and is an unusual manifestation of a mother’s anguish, rather than the more familiar figurines of impassive gods or heroes. Reaching across the centuries, it has the same emotional jolt as a photograph of a Ukrainian mother weeping for her dead son.

Just as affecting, utterly life-enhancing, is a tiny, crawling baby only 4.8cm long, which had lain hidden for centuries under layers of earth in sacred caves used for carrying out cult activities in Crete. Its copper form is a rare portrayal of anyone that young and, again, speaks of humanity and love.

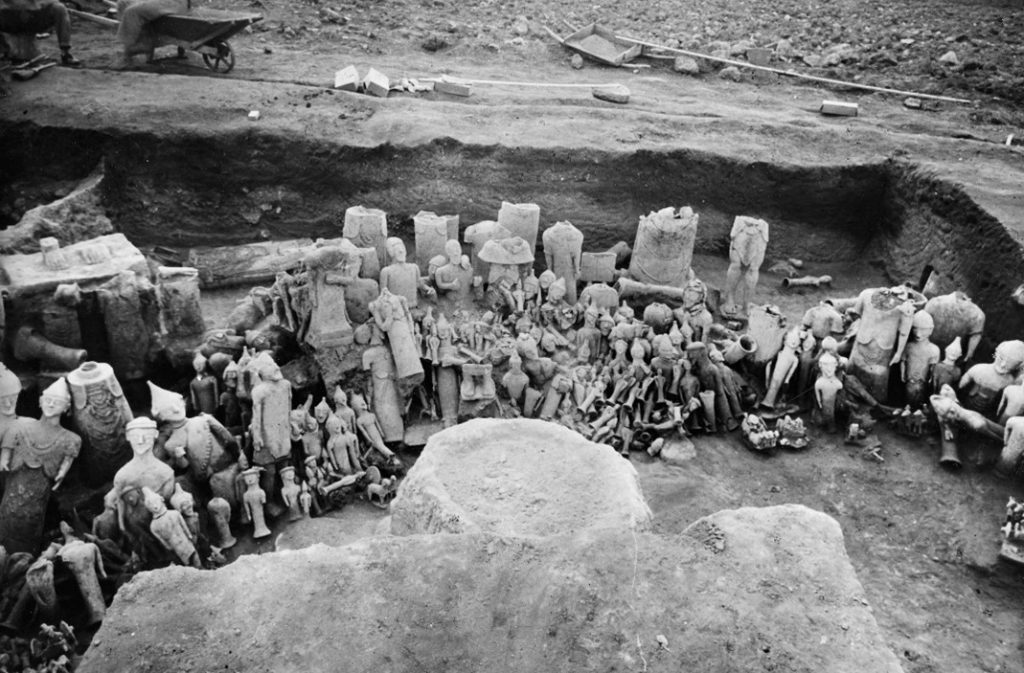

Amazingly well-preserved clay figures from the Cyprus Iron Age – 2,000 of them – were found in 1929 in an open-air sanctuary used for sacrifices. They include a group of charioteers, mythical creatures, a bull with snakes on its back and a woman with a little animal, perhaps a sign of the importance of farming. Inevitably known as Cyprus’s terracotta army, these are far more diverse and interesting.

Storage containers tell the story of food and how olive oil, wine, raisins, even perfumes were traded between the islands. One container is decorated with birds, animals and mythical creatures, which could be a marketing operation of some kind or maybe the work of an immigrant. The designs are associated with Anatolia, but the geometric shape of the vessel is Cypriot.

Death looms large. There are jars that contained the skeletons of sacrificed children, while bodies of adults were bound and squeezed into what looks like a small clay hip bath, until they decomposed. They were moved into a cave, their bones pushed to one side until the next body arrived.

They were buried with their possessions. An array of fearsome swords accompanied the funerals in Cyprus so that no one could use them in the afterlife, and a complex ceramic pedestal bowl decorated with horned animal heads, a bird and two miniature bowls on the rim shaped like tulips were an indication of the dead person’s status.

Some of the exhibits are there to be marvelled at; a golden diadem, a pendant and an earring from Cyprus, tiny lucky charms, and earrings decorated with the Egyptian god Horus, which were possibly introduced to Sardinia by the Mediterranean’s energetic traders, the Phoenicians, who first settled on the island in the eighth century BC.

Marvel, too, at the goddess Aphrodite, who rises above the exhibits in all her damaged glory. She used to stand proudly between the colonnades that lined the ancient gymnasium of the Greek city state of Salamis in the east of Cyprus, but after centuries her arms have gone, her head lopped off by Christians, her breasts disfigured. Yet somehow she remains a glorious figure.

Today Salamis is in Turkish Cyprus and they are laying claim to her heritage – not least with the plethora of cheap plaster-casts of the goddess that line every souvenir shop.

There is little to catch the eye with a batch of unexceptional clay pots tucked away at a far corner of the exhibition. They are likely to be the work of refugees who sailed to Crete, no doubt on small boats, centuries ago from Anatolia.

Then, as now, refugees were greeted with hostility, so this group hid themselves away high in the mountains of the north coast. Life would have been harsh: no arable land, only a few animals, but there were about 150 homes of people who scratched out a living for 100 years or so.

With the collapse of the Bronze Age in the 12th century BC, the inhabitants left the Cretan lowlands, and the refugees crept down the mountain and replaced them, working, farming and rebuilding the population.

As Christophilopoulou observes: “When the first refugees flooded into Greece from Syria in 2015 all the talk was that the country was being Muslimised. Fear and hatred was whipped up. ‘We would not be Greeks any more’,” was the sentiment.

“They were kept in refugee camps for two years or more, but now the Syrians have become useful in the islands off Turkey, like [Lesbos] and Samos. They have learned Greek, they work in the fields and they help the elderly. They have become assimilated and without them, the islands would suffer economically. People have always picked and chosen from other cultures.”

Islanders: The Making of the Mediterranean, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Until June 4. Richard Holledge writes about the visual arts for the Wall Street Journal, Gulf News, FT and New European