At the end of this month, it will be 50 years since the so-called Battle of the Sexes between Bobby Riggs, a pre-war Wimbledon champion-turned-self-styled male chauvinist, and Billie Jean King, the then reigning Wimbledon champion who was at the time leading a campaign for equal pay in the sport.

At the beginning of 1973, the US Supreme Court ruled that the constitution protected a woman’s right to have an abortion, which actually meant that a woman had agency over her own body. Just like a man did.

In fact, back then, no one questioned whether a man had agency over his own body, unless you were talking about African American men in relation to the police. Black men had no agency over their own bodies if pulled over by the cops, and events demonstrate that this is still true.

But no woman – whatever colour she was or station in life she had – was in total command of her person before 1973. A shocking thing to contemplate, but true.

Men and women lived in a different country. So this coming together of a 29-year-old woman and a 55-year-old man who had boasted that he could beat any woman, no matter her age, took on huge social significance.

Back then, I was working as a file clerk in a law firm in the equivalent of Chicago’s Wall Street; all suits and skyscrapers and secretaries like Mary Tyler Moore, with attitudes like Felicity Kendal: cute and tiny and smiling always.

I took classes at night so that I could graduate from university. I had hope that a degree would better my life. I was also told, almost within the first hour of employment at a top-drawer law firm, to make sure that I did not bend over to reach the files at the bottom of the filing cabinet in front of a particular lawyer; nor was I to ride the lift unless three women were in there with me. Three.

Being chased around the desk after the door was closed was normal. It was like a Carry On film without the laughs. We women traded these experiences and others over the water cooler or at lunch. There were water coolers then.

There was nothing and no one to hear you if you got trapped in a locked room with one of these officers of the court and, up and down the street, every woman passed on ways and means to escape men. You knew that the police would be of little assistance. Chicago cops, anyway, usually interrogated a woman: about what she was wearing, as if her clothing was the criminal. So Billie Jean taking a man on via live TV was important.

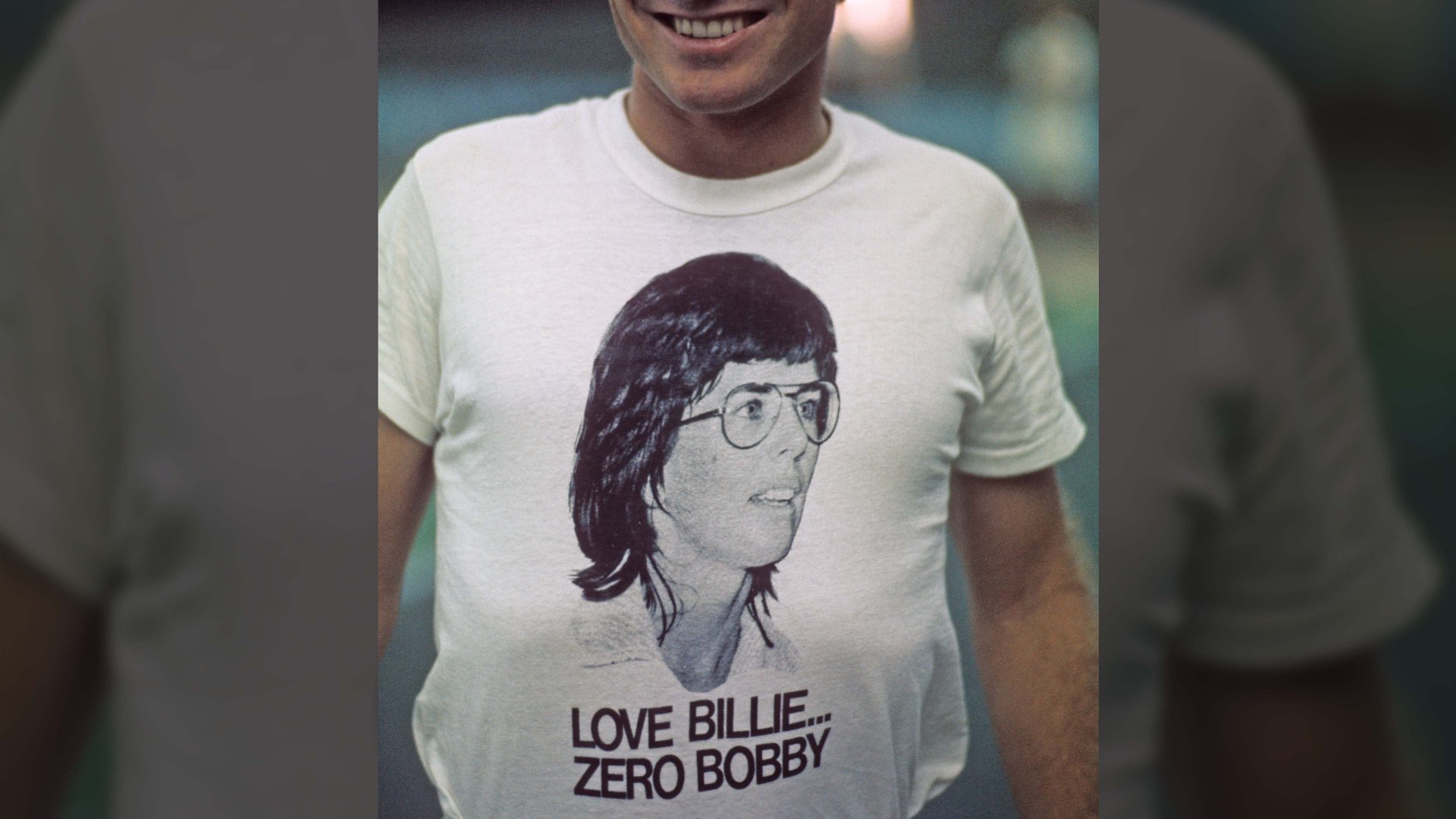

Bobby Riggs was a derisory, loudmouthed buffoon. He was always on TV, baiting women – and this was OK, even expected. It was even entertaining because he was so patently absurd.

And women who baited men on TV had to be old (by the standards back then), or be a comic genius like Phyllis Diller, who satirised every type of guy, with the kind of chilling precision that made you gasp even as you laughed. The likes of Mia Farrow, for example, would not have been able get away with it.

The battle itself was a farce, a clown show, and it was billed as one. There was a $100,000 winner-takes-all prize; that would be around £525,000 today. It was billed as an ABC Sports Special from the Houston Astrodome, so that guys would watch it, and they did – 90 million people tuned in worldwide. There were celebrity fans among the 30,472 in attendance at the Astrodome – George Foreman was a Billie Jean King supporter and Chris Evert backed Riggs. Howard Cosell, the nation’s number one sports announcer, the man whose opinion really mattered, was involved too.

The whole thing was in colour; at 8pm. And if you are too young to get what this prestigious time slot meant, it is impossible to explain how sacred the prime-time hour then was; and the weight it gave to things.

The age difference between the players was so huge that, viewed purely as a sporting event, it was ridiculous to begin with. And, of course, Billie Jean duly won. She was anointed to win for all of us “chased around the desks” women. Maybe, however tacky the event, that was significant in the times we were then in.

The top film in the month of the match was about a small-time depression-era gangster named John Dillinger, who got gunned down in my home town of Chicago in front of a cinema that was still in business at the time of the Battle of the Sexes. I think Dillinger was betrayed by a woman. Even if he wasn’t, he sure slapped quite a few around in the movie.

That same September, Marvin Gaye was singing Let’s Get It On at the top of the charts. Marvin could. We women couldn’t.

When you are considering the back-and-forth of things, I suppose tennis is an apt game. So what is the real significance of this anniversary? What does it mean?

Maybe it makes us look back at a time when women had gone to a new space, one that we hadn’t recognised but knew was there. Maybe it was about stepping out on the field, just being on it, no matter how ridiculous the circumstances were at the time, no matter how, in retrospect, trivial.

King became a standard-bearer for female athletes, women who compete seriously. This may seem an odd thing to say, but then serious competition was not assumed. What was assumed is that a woman would have a child, and that would be the end of it.

The stand that the Spanish football team has taken, for example, is about equality of agency. Billie Jean King participated in the Battle of the Sexes to show that the battle was not equal; that the battle was in a way a farce, and that the real battle is about the right and the welcome of women in sport as they are. As they want to be.

The term Battle of the Sexes is less applicable in American sport now than it is in American politics. Right now, at this time, it is hard for me to accept that I had more rights at 24 than a woman of 24 today has now in the United States.

When it comes to sport, the next battle is the one of the even playing field: which means serious money.

When a female athlete can create the kind of big money circus that Lionel Messi is doing in Miami at the twilight of his career, then the battle is over.

Well and truly. And in a strange way, sport itself will be better.