It was by a cruel twist of fate that on the day chosen to smuggle 41 works of art out of Kyiv, Russia subjected Ukraine to one of the heaviest bombardments of the war so far. Around 100 missiles were launched as two vans loaded with cultural treasures made their way to the Polish border, guarded by a military convoy.

“It was quite a dramatic process, I have to admit,” says Katia Denysova, who with Ukrainian colleagues, among them the art historian and curator Konstantin Akinsha, and multiple institutions across Europe has curated the most comprehensive UK exhibition to date on modern art in Ukraine.

Before opening in London, the exhibition toured Vienna, Brussels, Cologne, and Madrid, where the paintings first arrived in November 2022, their arduous journey across Europe facilitated by the Spanish-based collector Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza, whose father founded Madrid’s Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza. It was only once safely over the border into Poland that the art, most of which had been rescued from the National Art Museum of Ukraine (NAMU) and the Museum of Theatre, Music, and Cinema of Ukraine, could be insured.

But, explains Denysova: “That was also the day that a stray missile landed in Poland, and the border got closed. So we were potentially looking at the works being stuck on the border for a long period of time.”

In the end, diplomatic levers were pulled, and the vans were once again on their way. “But by the time they arrived in Madrid, I think even our Spanish colleagues were crying when they saw the vans arrive, because it was just such a dramatic couple of days getting them out of Ukraine.”

Though supplemented by private loans, the exhibition is principally comprised of works evacuated from Kyiv, a feat that stands as an act of resistance against the crushing influence of Russia.

Even so, the exhibition has bigger muscles to flex, and the unfamiliar spelling of such familiar names as Kazymyr Malevych tells its own story: Malevych, and his fellow Ukrainians Sonia Delaunay, and Alexander Archipenko, are usually understood if not as Russian, then as the product of a barely differentiated Soviet monoculture. Here, he is one of several eminent artists proudly reclaimed by a country that, though perpetually occupied, boasts a distinct culture of its own, one that in the first 30 years of the 20th century was expressed in vibrant and experimental art and literature.

At the turn of the 20th century, Ukraine was divided between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires. As part of the general suppression of indigenous culture, the Ukrainian language was banned, and its cities denied their own art academies.

Instead, young artists usually completed their studies in St Petersburg, and over time, Paris or Munich, where they encountered the many strands of modernist experimentation that flourished in these cities.

The Cubo-Futurist compositions of Alexandra Exter are vividly representative of this experience, and suggest not only her complete immersion in these new visual languages, but her peripatetic life, which took her from France, to Italy, Germany, Russia and Ukraine.

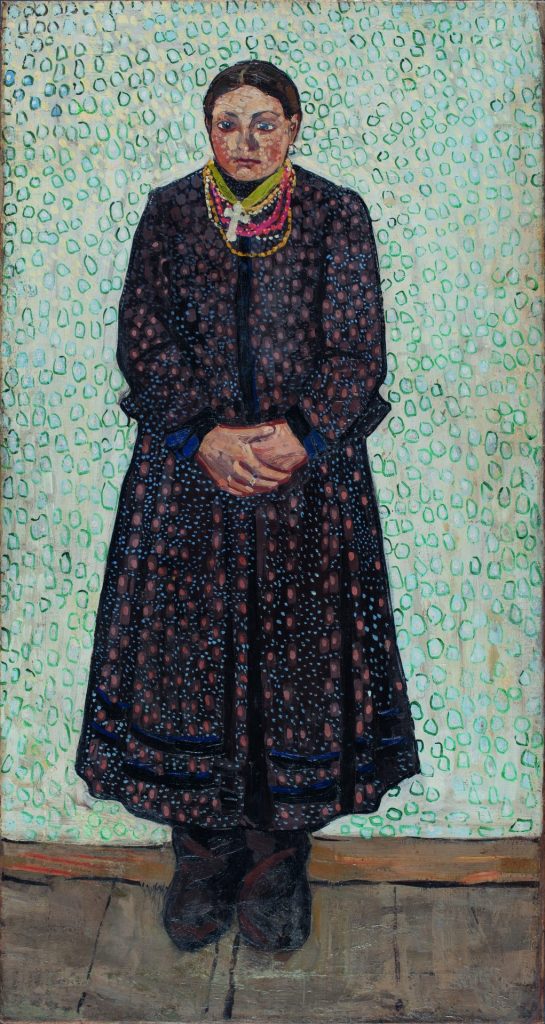

An interest in folk art – characterised as an example of so-called “primitive” art – was widespread among avant-garde artists like Matisse, Picasso and Modigliani for example, for whom it represented an intuitive form of expression, free from the constraints of traditional art education.

For Ukrainian artists, “folk” imagery and decoration served a different purpose, somewhat removed from the modernist project: for them it provided living subject matter that when given a modernist treatment presented an up-to-the-minute, uncompromising expression of national identity.

Colour is often used to denote a specifically Ukrainian character, and in Oleksandr Bohomazov’s 1915 painting The Caucasus, rich blues, reds and ochres describe a stylised landscape that switches between rolling hills and the sweeping curves of a decorative flourish, of the sort painted on to furniture, for example.

That this synthesis of folk art was assertive, rather than whimsical or nostalgic, is emphasised by its role in the concurrent blossoming of the theatre arts, which drew strength and vitality from a host of new writers and directors, and artists such as Exter. Her glorious costume and set designs are subtle, honed fusions of visual language, in which a graphic, hard-edged modernity combines with an unmodulated folk-inspired colour palette and stylistic elements particular to each play.

Commissioning many of Exter’s innovative designs was the now legendary director Les Kurbas, who in Kyiv and Kharkiv introduced a European repertoire that ranged from Shakespeare to experimental new writing, so marrying notions of progressive, European modernity with the revival of Ukrainian culture.

For the visual artists involved in the theatre, it was fertile ground, and Exter’s Kyiv studio trained a generation of theatre designers, among them Anatol Petrytskyi. His mixed media costume designs are among the most enjoyable exhibits here, and make use of such interesting materials as pearl barley, glued on to suggest the textures of fur and wool.

The significance of the theatre as a campaigning art form resonates today, as Ukrainian theatre once again enjoys a purple patch in a time of adversity. In Kharkiv, close to the Russian border, performances take place in subway stations, and in June this year, Ukraine held its first-ever Shakespeare festival in Ivano-Frankivsk in the west of the country.

A century ago, the combined events of the first world war, the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the October Revolution plunged Ukraine into turmoil. The Ukrainian People’s Republic, declared in 1917, was immediately locked in battle with the Bolsheviks whose victory in 1921 marked the foundation of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic (UkrSSR), with Kharkiv as its capital.

It is notable that in the dangerous and unstable period of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, the government sought to promote tolerance, one consequence of which was the foundation of the Kultur Lige in Kyiv in 1918, its mission to promote contemporary Jewish-Yiddish culture, under a modernist umbrella.

Despite such efforts, Jewish communities across Ukraine were subjected to pogroms between 1918-21. Though resolutely abstract, El Lissitzky’s Composition, 1918-1920s, expresses the horror of those years, its dark vortex punctuated by a shard of brilliant, metallic white, and vivid flashes of red. In Horse Riders and Sunrise, both from the late 1910s, Sarah Shor uses a similar placement of forms to create a horrible atmosphere of claustrophobia.

Though the advent of the UkrSSR brought the Kultur Lige to an end, Ukrainian art and culture flourished in the early Soviet era due to the policy of ukrainizatsiia (Ukrainisation) introduced as a strategic concession. The period of cultural prosperity that ensued was as calculated as it was liberal, and writing in the accompanying catalogue, curator Olena Kashuba-Volvach explains that it was “aimed at destroying the remains of the old imperial system and increasing the role of the central party leadership in the USSR republics by involving broad segments of the population in political life.”

So it was that in 1924 the Kyiv Art Institute (KAI) came into being, the successor to the country’s first art academy, the Ukrainian Academy of Art, which had been founded at independence in 1917. The KAI was both a place of artistic freedom and an organ of the Soviet machine, establishing itself as among the USSR’s leading art schools.

The span of work and styles that flourished there is remarkable, exemplified by the figure of Viktor Palmov who in the 1920s explored various idioms rooted in experimental colour combinations, and the fragmentation of space, used to dramatic effect in his 1929 painting The 1st of May, 1929.

When Malevych began teaching at KAI in 1929, he had abandoned the extreme abstraction called suprematism, which refused any reference to observed reality. Instead, he adopted a highly stylised, but figurative idiom, as seen in Landscape (Winter), after 1927.

Folk art was not the only seam of Ukrainian heritage mined by avant-garde artists in the 1920s, and the work of Mykhailo Boichuk and his followers, among the most influential artists of this period, draws on medieval art. Strong lines and frontal figures in flattened space recall aspects of Byzantine art, while muted colours applied with tempera, rather than oil paint, create an effect similar to fresco.

Based in Kharkiv, Anatol Petrytskyi practised a grim realism that has a depressing familiarity today. Exactly 100 years on, The Invalids, 1924, is as affecting as ever, as Ukraine’s families continue to suffer the consequences of war, persecution and oppression.

Ukraine’s cultural golden era came to an abrupt end in 1931, as the policy of Ukrainisation was abandoned, the intellectual elite purged, and Socialist Realism adopted across the Soviet Union. While in Russia, non-approved figures were branded “enemies of the people”, in Ukraine the term “bourgeois nationalists” was applied, a label that curator Konstantin Akinsha describes as “an altogether more emotive and destructive appellation.”

The destruction of Ukrainian literature and art that followed, “amounted to nothing less than mass cultural genocide”, he writes, and huge numbers of artists, writers, and theatre directors were executed, including Les Kurbas and Mykhailo Boichuk, with many others sent to labour camps. Huge quantities of art and books were destroyed or confiscated, and it was only after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 that Ukraine’s modernist history began to be rediscovered.

Thanks to multiple international efforts, many objects from Ukraine’s museums and galleries have been evacuated to safety. But Katia Denysova says that many remain, and while they are mostly in storage, their safety is far from guaranteed.

Last month, Alina Dotsenko, the director of Kherson Art Museum in southern Ukraine spoke to The Art Newspaper, and detailed the vast losses inflicted by Russian forces on that museum alone. “Before the occupation, our museum collection consisted of around 14,000 works of art. More than 10,000 of them were stolen”, she said.

While Russia insists that the art has been removed to safety, Dotsenko is clear that these are strategic thefts: “All of these crimes are the result of the Russian leadership’s single obsessive goal of absorbing Ukraine and destroying its identity. To call Ukrainian art Russian (the Russian Empire has been rewriting the identity of artists for centuries), to “re-educate” children, to “reprogramme” their consciousness so that they do not perceive themselves as Ukrainians – these are terrible crimes that must be stopped.”

Dotsenko is clear that as things stand there is no recourse to the law, and advises the international community to boycott Russian projects. Reasserting the sovereignty of Ukrainian culture is a meaningful action that can happen immediately, and later this year, a decolonisation guide is due to be published, aimed at helping museums dealing with Ukrainian heritage to better describe and contextualise their holdings.

In The Eye of the Storm is clearly a part of this process, a heroic and eye-catching story that will have truly done its work once museums around the world can differentiate between Russian and Ukrainian artists, allowing Ukraine its own remarkable voice.

In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s is at the Royal Academy of Arts until October 13, 2024