To say the cartoons of William Heath Robinson are complicated is somewhat like saying the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is colourful. To say they are quintessentially British – English, even – is like calling the ceiling of St Paul’s Cathedral is a bit domey.

Born in Islington in 1872 into a family of illustrators, his drawings conjure up a world of pulleys, wires, string and cogs powered by steaming kettles and kept running by balding, bespectacled men who look like clerks in a high-street bank – when there were high-street banks with clerks.

They appear convoluted – well, they are convoluted – but in fact have a perfect logic about them, working in a finely tuned, ramshackle harmony, as the country was then supposed to.

Take Rational gadgets for your coupons: doubling Gloucester cheeses by the Gruyère Method drawn in May 1940. In true Heath Robinson style, a gallimaufry of contraptions, prodders, slicers and dicers whirling thingamajigs, and a giant prong manoeuvred by moustachioed workers contrive to make a barrel of cheese go further in ration-hit Britain by gouging out Gruyère-style holes in it. In its own way, perfectly logical.

An exhibition of his work to mark what would have been his 150th birthday has opened at the delightful Heath Robinson Museum in Pinner, Middlesex, where he and his family moved. It celebrates the versatility of his talents, including some of the landscapes with which he really wanted to make his name, until he discovered cartoons paid the bills more readily.

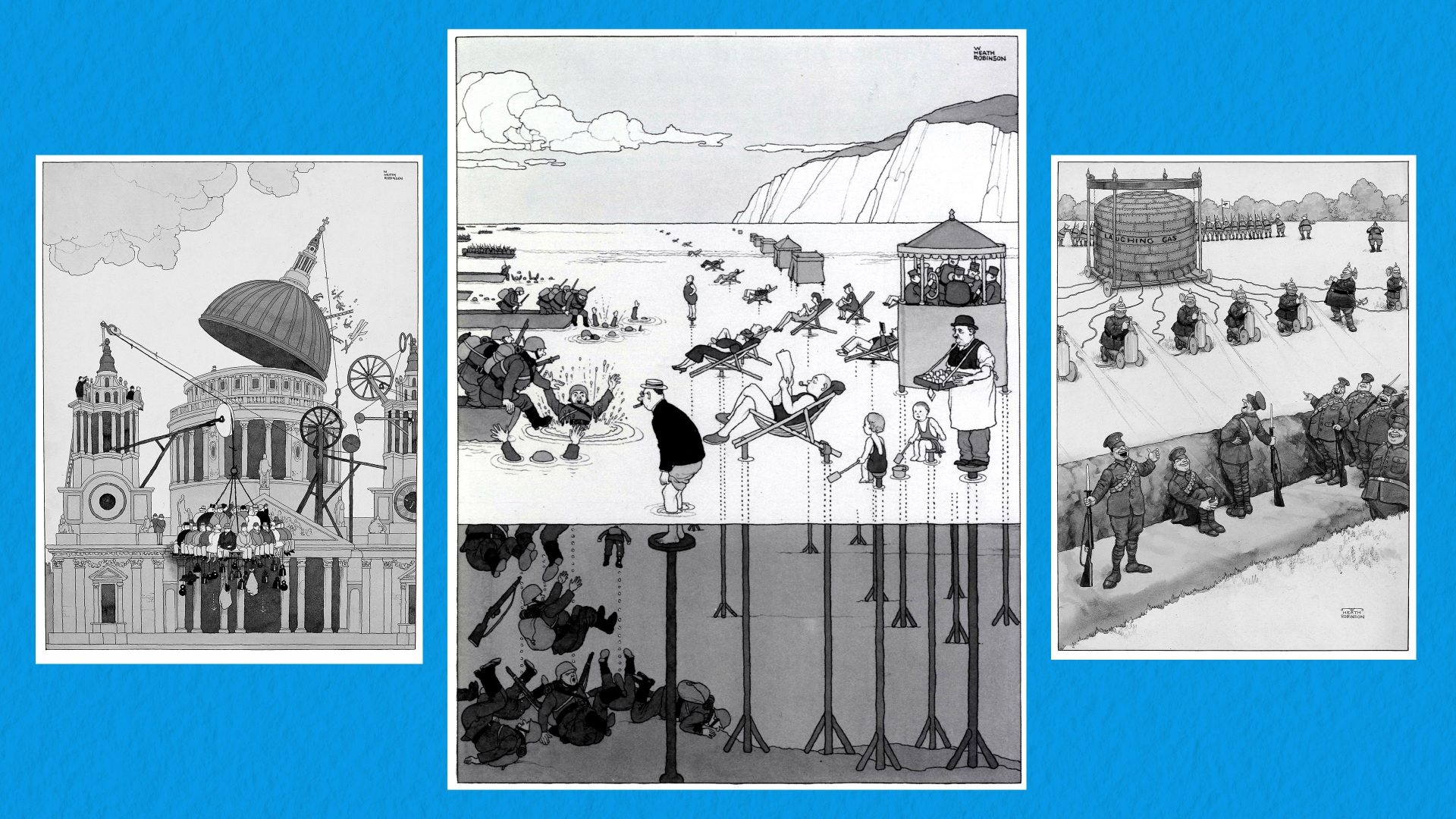

The phrase “a Heath Robinson contraption” made its way into the Oxford English Dictionary in 1917, and by then Robinson was producing the first of what comprise the most surprising images in the show – cartoons drawn for both world wars.

While many cartoonists opted for damning imagery, savage indictment and justifiably savage propaganda against the foe, Heath Robinson employed a deceptively deprecatory humour that presented the British as amiable innocents caught up in something they didn’t quite understand – or seemed not to – while the Hun was portrayed not so much as a beast but as a buffoon. PG Wodehouse would have felt at home.

Robinson eschewed caricature and jingoism in favour of playful absurdity right up to the long illness that would kill him in 1944, but this was not always the case among his peers. Bruce Bairnsfather, a Royal Warwickshires machine-gunner shellshocked at Ypres in 1915, was one who continued to

plough his own furrow. His best-known cartoons featured the belligerent Old Bill, a walrus-moustachioed veteran. Peering grumpily around as bombs explode above the trenches and bullets whizz by he grumbles to his comrade: “Well, if you knows of a better ’ole, go to it.”

Scottish artist Archie Gilkison displayed a similar lightness of touch at the beginning of the war with a small boy on Christmas Eve 1914 catching Santa putting toys in his stocking but saying plaintively that if they were made in Germany: “I can’t, you know.” Yet by 1916 Gilkison’s work featured unsparing

scenes of horror, though perhaps the most poignant is that of a German soldier lying dead in a ditch, his bayonet pointing hopelessly to the skies in a

painful contrast to the bombastic rallying cry of the Kaiser: “I know that my glorious army will never retreat”.

Many cartoons were drawn to shock and strengthen resolve by showing the enemy as vile creatures who deserved no mercy or compassion. The figure of death with his scythe is familiar, the four horsemen of the Apocalypse gallop through the pages. One French cartoonist depicted the Germans as

bugs. “Oh! Les sales bêtes,” (“Oh you dirty beasts”) the soldiers cry as they blast

away with cannon and insect repellent. Just as uncompromising, an English

cartoon showed the devil and a German soldier looking at a monthly report with numbers of innocent civilians – babies 164, children 178, women 292. “A good month’s business,” they gloat.

Cartoons were also used to rally the people, with posters like the brutally direct Destroy this mad brute – Enlist by the American Harry R Hopps, which was released in 1917 and portrayed Germany as a slavering gorilla with a cudgel in one hand and a fair maiden in the other.

We see it too with the war in Ukraine. To take only two; the Times cartoonist

Peter Brookes depicted Putin as the family butcher holding a chopper and

standing in front of the blue, white and red of the Russian flag. For red, read

blood. In France, satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo ridiculed lack of government action with three snowmen sporting red hats and carrots for noses, standing feebly by a barbed-wire border. The caption derisively reads: “Ukraine: France sends in its most dynamic forces.”

The Brookes cartoon would be too brutal for Robinson, Charlie Hebdo’s too

sharp but with his deceptively gentle satires he got as close to the cruel absurdities of war as any war cartoonist. In his series German Breaches of the Hague Convention, which included the enemy’s use of deadly mustard gas,

Robinson showed the enemy showering the British with laughing gas. The result is that our boys fall about with mirth at their foes, who look on frustrated.

A series of cartoons lampooned German boasts of imminent superweapons, with Nazi troops aboard flying tanks with retractable wings, or landing craft being blasted towards Dover from giant cannons. The British are seen as equally cunning – steering half-width tanks through narrow gaps between rocks in the Libyan desert; using a fake set of rooftops held vertically in Deceiving Nazi Dive-Bombers by using dummy rooftops set vertically, dressing as Stonehenge’s standing stones to repel invaders on Salisbury Plain.

Again, there is a sharp contrast with what contemporaries were producing. In November 1939, the Daily Mirror’s Philip Zec showed a German worker tied to a wooden stake, no doubt left to die, together with a quote from Hitler, “In Germany there is Happiness and Beauty”.

Weeks earlier, Robinson produced A Cleverly Camouflaged All-ways Gun, mocking the Führer’s claims of elaborate fortifications behind their frontlines.

The Standard’s David Low did his bit to raise the nation’s spirits by portraying a defiant fellow in a cloth cap with fist raised, proclaiming: “And we can still

take it”, or showing a determined public, led by Winston Churchill and the

wartime cabinet, striding out, rolling up their sleeves with the caption “All behind you, Winston.” Meanwhile, Robinson did his with his invention of The Hit-or-Missler Gun, for Firing in all Directions at One Time, which seems to take out the Nazis by mistake.

Perhaps these two approaches hint at two views of Britain that persist today – the rugged, unconquerable island nation so fondly promoted by the Brexiteers, or the slightly flimsy country which just about muddles through while laughing at its own absurdities.

Or perhaps it is as cartoon expert Prof Laurence Grove of the University of Glasgow says: “It is all about propaganda and humour is important for that. Not many things are less funny than wars and as cartoonists they can go the

opposite way with the material they have. One of the best ways to support the war effort is to make light of it – it’s their job to make people laugh.”

The Humour of Heath Robinson, The Heath Robinson Museum, Pinner, Middlesex, until September 4