On the morning of October 11 this year, Paolo Salvaggio, a convicted Mafioso drug dealer living under house arrest in the Lombard town of Buccinasco, set out for his two permitted hours of daily exercise, on a bicycle. Salvaggio was terminally ill, and believed to be still involved in the cocaine business, despite his conviction.

Before he had reached the nearest intersection, two men on a T-Max scooter pulled up alongside. The pillion rider fired a shot into Salvaggio, hitting his shoulder, then they finished him off with a colpo di grazia to the head.

“A new Mafia war is taking place in Buccinasco,” said Rino Piuri, the town’s Mayor. “A shift in power, and a clear message, delivered in broad daylight. The killers didn’t care about hurting other people, or being seen.”

The president of the regional AntiMafia Commission, Monica Forte, called the killing “a brazen execution, but also a demonstration of power and impunity”.

Another intra-Mafia hit – so what? There were some notable elements to the slaying which sent a depressing chill down the spines of those who hoped this centuries-old scourge of Italian society was under suppression.

The assassination happened not in Sicily, Naples or Calabria, but at the gates of Italy’s dynamic economic capital Milan, a città-mondo, as the Italians say. A city at the crossroads of Europe, which recently re-elected as Mayor one of the continent’s most enlightened and progressive politicians, Giuseppe Sala, chairman of the task force on urban management and climate initiatives for the C40 network of world cities.

And this was not the work of the infamous Cosa Nostra or the Camorra, but the ’Ndrangheta of Calabria, the least-known of Italy’s major Mafia organisations, but today its most corrosively powerful.

As the Camorra and Cosa Nostra have receded in strength in the past three decades, the ’Ndrangheta have established themselves a national power in Italy, migrating to the economic and industrial powerhouse of the north from poverty-stricken Calabria – the toe of the Italian boot kicking Sicily.

This geographical migration mirrors a migration in purpose; more than any crime organisation in Italy, the ’Ndrangheta operate with the sensibilities of a multinational corporation … albeit one that with an appetite for brutality and murder.

There are two caveats to any consideration of the Mafia in a UK publication. One is to confront the North European, specifically British, stereotyping of Italian society: either Tuscan paradise or Mafia hell. It needs saying that the vast majority of Italians go about their lives largely oblivious of, and unaffected by, the Mafia (and not do they live surrounded by cypress trees sipping Chianti Classico).

The other is to acknowledge an uncomfortable reality, as articulated by the most famous observer of organised crime, Roberto Saviano, author of Zero Zero Zero. Saviano – who lives under armed escort after his work on the Camorra – opened his session at the Hay Book Festival in 2016, thus:

“If you ask me which is the most corrupt country in the world I will tell you: it is the UK. Not because of your bureaucracy or state, but because the criminal money of the world is cleaned here.”

Some of the Italian Mafia’s profits are reinvested and laundered in Italy, but the vast majority is deposited in, and move with impunity, through the global banking system, much of it through London.

We must also think in terms of “narco-genealogy” – the mutation by criminal organisations from one generation to the next, as each adapts to the market, or directs it. The old pyramidal, patrician syndicates such as Cosa Nostra (and Mexico’s Guadalajara cartel of the 1980s), with their cupola and clear chains of command, gave way to leaner, meaner, looser organisations without pretensions of “honour”, syndicates which practise “austerity” and are horizontally, rather than vertically, organised, as are the Camorra and ’Ndrangheta.

The insidious manner in which their presence becomes embedded in society was well illustrated in Franceso Patierno’s 2018 documentary Camorra: Cigarette smuggling organised on enormous scale by the Camorra deployed thousands of ordinary men, women and children to sell their contraband on the city streets – an activity that, although illegal, would not provoke action from the authorities.

Thus the livelihoods of tens of thousands of Neapolitans was jeopardised by any crackdown against the Camorra. Any politician attempting such faced resentment from the electorate.

So what is the Italian Mafia now, who is doing what, and how?

Saviano sums up the balance of power. “Cosa Nostra [the Sicilian Mafia] is in deep crisis,” he says. “After having committed atrocities, it has been the most penalised, and under the leadership of the Corleonesi clan, has, in a way, committed suicide.

“The Camorra is more visible than the ’Ndrangheta, which has focused on discretion – never ostentatious, acting in silence.

“The ’Ndrangheta is the most powerful organisation, with a strong presence in Northern Italy, where it resorts, without hesitation, to the same violent methods it uses in its Calabrian strongholds.”

The Italian parliamentary AntiMafia Commission’s report of 2018 drew a map of what it called “the evolution” of organised crime on the eve of the Covid-19 pandemic, after what it claimed was the “decapitation” of the Sicilian Cosa Nostra through arrests and trials.

The report finds Cosa Nostra capitalising on the arrival of migrants from North Africa, and engaged in a “strategy of submersion” after its ultra-violent periodo stragista. (Stragismo is hard to translate; something between terrorism and outrage.)

The ’Ndrangheta, says the report, “is the most dangerous Mafia organisation in Italy”, with the capacity to “challenge the state without combating it overtly”.

It is engaged in “acquiring control, directly or indirectly, of businesses operating in various sectors, including construction, transport, gambling, garbage disposal”.

In addition to the native clans, a new Nigerian Mafia has gained a foothold in Italy, hitherto operating under a “franchise” system, beholden to indigenous syndicates, but now asserting its own power.

One of the world’s leading academic analysts of global organised crime, Federico Varese, a professor of criminology at Oxford University, locates Nigerian clans in his home town of Ferrara, from where it directs narco-traffic across wealthy Emilia-Romagna, in particular the city of Bologna.

The term ’Ndrangheta derives from the Greek andragathía (bravery or virtue) and ’Ndrina; “a man who holds fast”.

Few families understand better the evolution of modern Italy’s crime organisations than that of a man who held fast against them: General Carlo Alberto dalla Chiesa.

During the so-called years of lead – murderous attrition during the 1970s between the far left and right, the state and Mafia – the carabinieri general was appointed to crack down on political terrorism, which he did, especially against the Red Brigades.

For his success, Dalla Chiesa was awarded the prefecture of Palermo, in May 1982, with special powers to break the Mafia.

The response came four months later: the general, his wife Emanuela Setti Carraro and their bodyguard were killed when a squad of sicarios on motorcycles forced their car off the road.

The general’s son Nando became a parliamentary deputy for the centre-left Democratic Party, and now teaches sociology at Milan University and runs an observatory that monitors matters Mafia.

Dalla Chiesa Jr.’s most poignant book may be that about his father’s murder, but his most important is Passaggio a Nord (Northern Passage), which is about what he calls “la grande rimozione” (the great transferral) of Mafia infiltration into the northern economy, led by the ’Ndrangheta.

Dalla Chiesa traces the why, wherefore and nature of ’Ndrangheta penetration of the north: its “systematic, aggressive and determined presence in the economies of construction, public works, tourism, agriculture and garbage disposal”.

An example of the ’Ndrangheta’s presence in the north, observes Dalla Chiesa, was an aggressive intervention of one of Europe’s most advanced hospital systems, in Lombardy between 1995 and 2013, during a vast privatisation scheme, It happened under the governorship of Roberto Formigoni, a protégé of then prime minister Silvio Berlusconi.

“Health services,” wrote Dalla Chiesa, in Passaggio a Nord, “present a formidable accumulation and lubrication of personal dependencies, an indispensable resource in the realisation of a Mafia model” – a prescient analysis affirmed by Covid-19.

“Since the 1980s, there has been a recycling [or laundering of Mafia money] in medical laboratories and clinics, which have opened their doors to new profits.” In 2019, the Italian edition of Business Insider magazine published an investigation into the contamination of the Lombard health system by ’Ndrangheta, revealing how clans were mobilising their own children to train and enrol as nurses and chemists.

“The ’Ndrangheta entered Lombard society like a blade through butter, transforming it,” Dalla Chiesa writes. Reflecting on the Buccinasco murder a decade after the book, he adds: “It’s difficult to say why he was killed, or who by.

“It was probably due to some breach of the rules of territory. But whatever it was, it was a declaration of power, and it happened in the north. Something that they have not done for some time.”

In his book Mafias On The Move, Federico Varese traces the forensics of the ’Ndrangheta’s advance into the northern boomtown of Bardonecchia, on the French border.

The Mafia begins with a physical presence, he argues, thanks to Italy’s system of internal exile of criminals, which then preys on – but protects – illegal migrant labour, and eventually controls the local political and with it economic infrastructure.

Professor Varese says: “The idea that the ’Ndrangheta doesn’t kill is clearly awry.

“The Mafia has to kill, that is their business. They do try to keep violence at a low level, especially outside their own territory.

“But the threat of violence is always there, it’s just a question of using it wisely. No one wants internal wars or to kill prosecutors if this can be avoided. Usually, violence is a sign of failure or weakness.”

This January saw the start of the biggest Mafia trial in Italy since the prosecution of 450 Sicilian mafiosi in the “Maxi-trial” of the 1980s. Unlike its Sicilian precedent, the trial in Calabria commands little media attention. But 900 witnesses are testifying against 350 defendants, including one of the first pentiti to emerge from the ’Ndrangheta (The Italians use the word “repentant” as opposed to the English term “supergass”). Emanuele Mancuso, is taking the witness stand against his uncle, Pantaleone Mancuso.

The ’Ndgangheta’s organisation around blood ties has made it almost impenetrable until now. Professor Varese says: “The fact that a senior boss testifies against his uncle … that’s breaking the family’s omertà.

“Something new is happening in the criminal galaxy that goes by the name of ’Ndrangheta,” he continues. “Historically, this was the Mafia with the fewest pentiti. But today the silence is beginning to crack even in the families of ’Ndrangheta.”

At the heart of this event is Nicola Gratteri, chief prosecutor for Catanzaro, who brings the case, saying: “This trial is for all honest businesses and citizens who have suffered the assaults and intimidation of the bosses. It is my hope that these proceedings can bring about a rebirth for the people of Calabria, weary of living with the ’Ndrangheta”. Since 2016, Gratteri’s warrants dispatched a special carabineri unit called I Cacciatori – the hunters – to arrest people hiding within tunnels, manholes and trapdoors, frugal hermitic mafiosi at the heart of an international criminal empire with an estimated annual turnover of £45bn.

“The Maxi-trial is the beginning of the end of impunity in Calabria,” says Dalla Chiesa, “even if not the end of the ’Ndrangheta. It will impact the ’Ndrangheta north and south, because it removes that impunity.

“Once impunity is taken away, the organisations have to respond, and something has to change.

“If the prosecutors achieve definitive sentences en masse, this will be the end of a culture of infinite crime in Calabria”. But Dalla Chiesa reminds us, ominously: “It was after Cosa Nostra lost its impunity in Sicily after the Maxi-trial of the 1980s, that the outrages followed”.

Professor Varese adds: “Trials and the end of impunity are crucial, but the underlining economic and social reasons why a Mafia exists must be tackled, and that can be done only by politics, not the judiciary.

“Italian politicians should do more: the Mafia has dropped off the political agenda.”

Most observers of the Mafia agree that the all-out war waged between Cosa Nostra clans in the 1980s, the “Maxi-trial” from 1986, and breaking of John Gotti’s Gambino clan in New York marked the beginning of the end of the Sicilian Cosa Nostra’s reign, nationally and internationally.

Francesco La Licata was a friend – and became the biographer of – high profile anti-mafia judge Giovanni Falcone – who would be assassinated by car bomb in 1982. La Licata is the oracle on the subject of Cosa Nostra.

He recently co-wrote the screenplay for the international hit film The Traitor, about pentito Tommaso Buscetta, Falcone’s star witness in the 1980s Maxi-trial. “And I remember that moment during the proceedings when Buscetta points at the mafiosi and says: ‘They say I destroyed Cosa Nostra, but it is not I who destroyed Cosa Nostra, it was Salvatore Riina who destroyed Cosa Nostra’.”

Totò’ Riina was boss of the Corleone clan, arrested in 1993 for the murders of Falcone and Borsellino and more besides; he died in 2017. “Riina destroyed the Mafia,” says La Licata, “because he embarked on the strategy of stragismo – of total war against the state, for effective control of political and civilian life. The state could not tolerate this level of violence, and had to fight back as hard as it could.”

The reign of Silvio Berlusconi, following this period, brought ambassadors from Cosa Nostra and his business empire to the heart of political power, under what is known as Il Patto – the pact between the Mafia and the government during the 1990s.

So Cosa Nostra will never die, but “it has degenerated,” says La Licata.

Successive reports by the Investigative AntiMafia Directorate (DIA) indicate young mafiosi in Sicily trying to reconstruct some echo of the old cupola, to coordinate the clans. Moreover, says La Licata: “Cosa Nostra has ceded control of drug-trafficking, which is now almost in the exclusive hands of the ‘Ndrangheta.”

“The Sicilians,” says Professor Varese, “have been pushed out of the drugs market. The containers are not coming into Palermo any longer, but into Gioa Tauro, a port built and controlled by the ’Ndrangheta.”

And now there’s another opportunity for all Italy’s Mafia clans.

The Covid pandemic proved a boon to Italy’s Mafia syndicates. Roberto Saviano explains. “With Covid, Mafia families with more liquidity invested in the catering and tourism sector, taking over hotels and restaurants in difficulty.

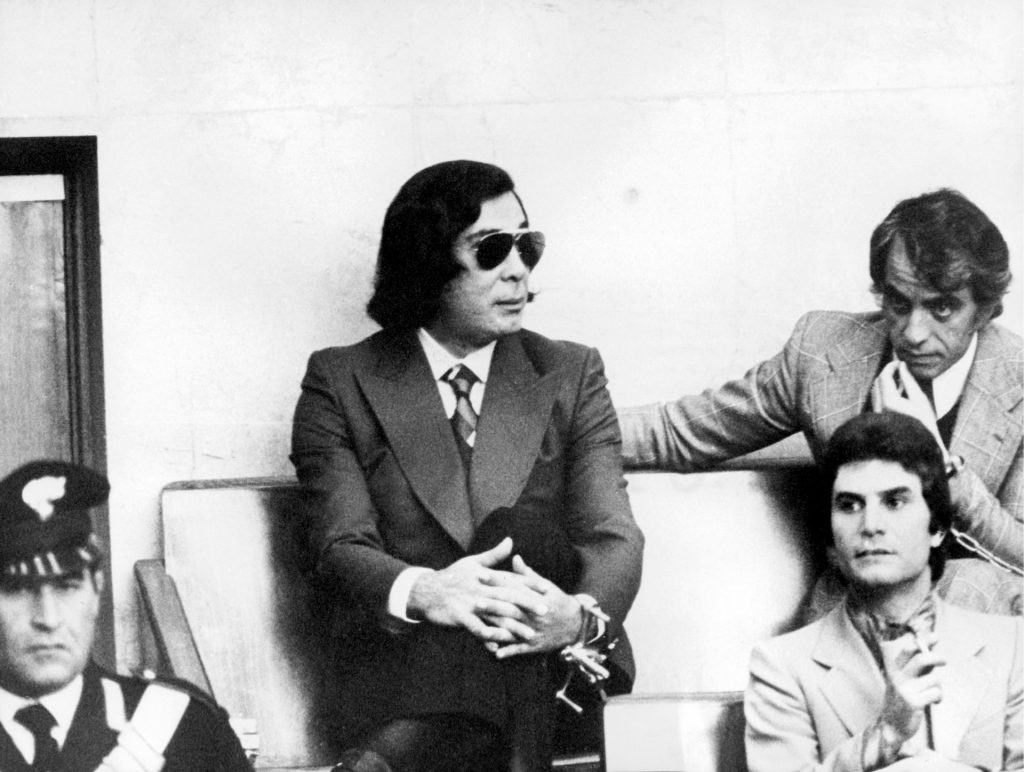

Camorra in 2017. Photo: Kontrolab via Getty Images

“Today, the extortion is no longer taking money, but giving money to businesses and companies. During the pandemic, clans supported businesses in crisis by lending money to owners.

“By doing so,” he says, “they took possession of these activities, leaving, only formally, the old owner, as a ‘wooden head’ [aka figurehead], so that that company would appear legitimate, and eligible for government aid to activities undermined by the pandemic.

“So, in addition to taking over the companies in crisis, the clans have also managed to obtain public funding.”

One investigation found the ferocious new Foggia Mafia in Puglia extorting funeral homes for each coffin during the pandemic. Professor Varese pointed out that this is, of course, classic Mafia modus operandi.

“When the Great Depression hit in 1929, Lucky Luciano suspended the collection of ‘mob tax’ from the workshops in the garment industry in New York,” he wrote.

“His organisation also offered loans to small businesses so they could weather the storm, often in exchange for a stake in the firm. This led, ultimately, to the Mafia being further entrenched in the legal economy.”

Saverio Lodato, author of the definitive history of the modern Sicilian Mafia, Quarant’anni di Mafia (Forty Years of Mafia) subtitles the volume Storia di una Guerra Infinita (History of an Infinite War).

He believes the Mafia’s continued evolution into the 21st century is facilitated by its cohabitation with the state. “The Italian state has demonstrated that it knows how to conduct the struggle against the Mafia up to a certain point, but not beyond that point.”

“Money laundering remains the great problem and the great European weakness”, insists Saviano.

“London today is more important than Panama from the point of view of recycling money, because with the Overseas Territories and the British Dependencies it is at the centre of a vast offshore financial network of tax havens. But also Malta, Cyprus, Andorra, Lichtenstein, Holland, Luxembourg –all territories used for recycling. The Netherlands has a central role: large multinationals are moving there because not only for important tax advantages, but also access to a privileged legal system for companies, fast and dedicated to the business. The killing of a journalist, Peter de Vries, by an ambush in Amsterdam is proof that the public and authorities in the Netherlands are completely unaware of what is happening.

“The perception is that so long as there is no blood on the ground in one place, the Mafia is apparently not there. But clans today think much more like multinationals than like criminal gangs.

“Continuing to consider the Mafia as a purely Calabrian, purely Sicilian, Neapolitan or Italian problem would be like considering “Amazon as a small Seattle start-up. The businesses are different, of course, but the business strategies are the same.”