To call an exhibition Between the Sheets can really mean only one thing; sex. Maybe love, maybe marriage, but above all what goes on in bed. That’s the provocative inference to be drawn from an exhibition of intimate paintings by JMW Turner (1775-1851) which the horrified Victorian critic John Ruskin deemed “a failure of mind”, because they were too rude and risqué for his refined eyes.

What a contrast to Turner’s stirring sea scenes, bucolic landscapes, mountains and moody ruins of which Ruskin so approved. What a different

perspective they throw on a man who was obsessively secretive about his life

away from his work.

The co-curator of this exhibition, Dr Jacqueline Riding, who was an adviser on Mike Leigh’s film Mr Turner, says: “We almost know minute by minute what Turner was doing in terms of sketching, travelling and exhibiting. The one thing we really couldn’t find a lot of information about was his private life, and even more so his relationship with women.”

Riding’s co-curator is Franny Moyle, the author of The Extraordinary Life and Momentous Times of J.M.W. Turner and together they have created an exhibition that fleshes out the character of this most private and secretive of men with 10 paintings taken from the Tate Gallery’s vast Turner collection. These have been displayed, appropriately enough, in a bedroom at Sandycombe Lodge, in St Margarets, near Richmond in Surrey, which the artist designed and lived in as a country retreat.

Turner’s attitude to love and marriage, women and sex appears to be contradictory. “I hate married men,” he wrote to his engraver JT Willmore.

“They never make any sacrifice to the arts but are always thinking of their duty to their wives and families or some rubbish of that sort.”

So far, so curmudgeonly. But he also lamented: “What may become of me I

know not what, particularly if a lady keeps my bed warm and last winter was quite enough to make singles think doubles.”

It appears he succeeded in keeping his bed warm from the age of 25, when

his first great love ended in rejection, and although he never married he was

to keep several mistresses who were to bear him four illegitimate children.

He had a sporadic relationship with Sarah Danby, whose family had been neighbours of the Turner family in Covent Garden, where Turner himself

was born. The affair began after she was widowed in 1798 and they had two

daughters together. But Turner saw little of them. Instead, he spent most

of his later years in Chelsea with the twice-widowed Sophia Booth whom he

had met in 1833 when she ran a boarding house in Margate.

Described as a “big, hard Scotchwoman”, Turner kept his life with Sophia as secret as possible, even adopting her surname. The combination of his portly five-foot-high physique with this “tall lusty woman” earned him the soubriquet “Puggy Booth”. In the 2014 film Mr Turner, the artist has perfunctory, unkind sex with his young housekeeper, Hannah, but there is no proof this happened. It was a typical moment of improvisation by Leigh.

But Turner was also single and unencumbered for many years, free to do as he pleased, go wherever he chose, travelling abroad to Germany, Austria and Switzerland as well as to Italy, and that most licentious of cities, Venice.

What do the sketches of bed and boudoirs tell us about the man, as in truth they are as blurry and ill-defined as the artist himself? First, as Riding says: “He is not the first artist to draw nudes! We have to put the paintings in the context of an artist’s formal training. Even if you are a landscape painter you

start your training on the human form, it’s an essential building block.”

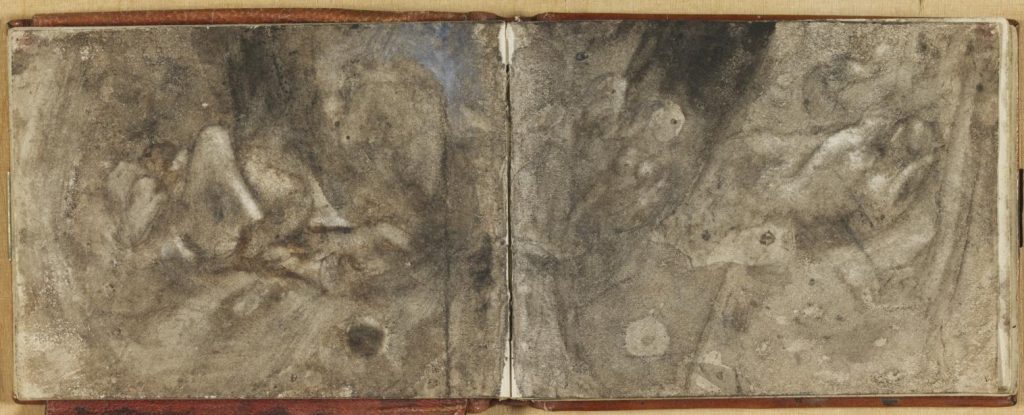

That’s very evident from Nude Swiss Girl and a Companion on a Bed, taken from the Swiss Figures Sketchbook (c.1805), which he compiled during his travels after 1802. A naked girl is entwined with another figure. Is it a man or a woman? It’s not clear. There is a discarded Swiss dirndl on the floor as well as two hats, but the second figure on the bed seems to be reclining on yet

another hat. Was someone else involved? Was this a fantasy of a lesbian encounter by the painter? Was he looking on, paintbrush in hand? What

seems obvious is that this, like the other sketches, was for his eyes only.

Perhaps there was something of the voyeur in Turner. He was a frequent

visitor to Petworth House in West Sussex, the home of Lord Egremont, an enthusiastic art collector and patron to Turner, who was notorious for his louche behaviour, and said to be the father of at least 40 illegitimate children.

No doubt Turner took advantage of the libertarian mood of the place with

daring bedroom scenes. One of these, A Figure in Bed (1827), showed a woman deshabillé sprawled in a four-poster bed, sheets in disarray, clothes

scattered carelessly around while An Empty Bed (1827) suggests its occupants had enjoyed a night of abandon. Had he been part of the romp? That scene is mirrored in the four-poster bed in the room next to the exhibition, which has been fitted out with rumpled sheets and a discarded shift and adds to the

undertow of prurience.

Given the bohemian nature of the place it’s quite possible he could simply have dropped by a lady’s room while she was still in bed and been only too happy to be sketched or, as Riding says: “You can take them any way you like. It could simply be that he got out of bed and sat on the other side of the room to draw the scene. He was interested in everything.

“It all starts with the eye of the artist. They will paint anything in front them, like Van Gogh painting a chair. While Turner is travelling he draws what he sees, whether it’s a castle in the distance, a fish he has just caught in the Thames, or a naked woman on his bed.”

Several years later on a trip to Venice, which was famous for its brothels and sexual licence, he painted the moody Two Semi-Clad Women at a Window in Venice, Conversing with Men Below (1840). Some have suggested he was inspired by Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet – despite the play being set in Verona and despite the painting portraying two women leaning from a window, instead of the solitary Juliet. What’s more, one of the women appears to be topless and chatting up the men under the balcony. There is a suggestion that Shakespeare’s Desdemona is the subject of A Nude Woman Reclining on a Bed, with another Figure or Figures, Venice (1840), but the shadowy naked figure is a far cry from the fragrant heroine.

So much of what we see is open to interpretation and guesswork, affairs hinted at rather than shown. But not so A Curtained Bed, with a Naked

Couple Engaged in Sexual Activity (c.1834–6), which peers into the murky

depths of a four poster and leaves little to the imagination.

Similarly, A Reclining Nude Woman with her Legs Drawn Up (c.1833) is an explicit portrayal of a woman perhaps in sexual ecstasy or perhaps, more prosaically, posing for the artist. There is quite an erotic charge to the small,

misty image, with what one biographer described as the “blushing pink tone of female flesh” contrasting with the dark dash of pubic hair.

Should we see them as proof of a dark side to the artist? In 1820 he inherited several properties in Wapping from an uncle, one of which he turned into a pub. Rumours spread that Turner availed himself of the prostitutes who frequented the docks and would stay in some “low sailor’s” house in Wapping or Rotherhithe on a Saturday, where he would “wallow ’till Monday morning”. But a friend derided the rumours as no more than “magpie stories which find admission into the pages of the newspapers”.

There were prostitutes in Wapping, but not all pubs were frequented by them. All we can do is speculate on what the area was like and be wary of

later accounts by disapproving Victorian biographers who spiced up accounts about the East End of London and could not resist dragging Turner into the grubby scene.

What the curators are keen to emphasise is the evidence of good-heartedness towards women. A Sleeping Woman, Perhaps Mrs Booth (c.1830-40) apparently shows his long-time companion in a “tender, candy pink sketch” reclining in bed with her breasts exposed.

“You can feel the tenderness, you can feel the relationship,” says Riding. “There were women who managed to break through that carapace of secrecy and with whom he felt comfortable. Clearly Mrs Booth was one of them because they spent nearly 20 years together.”

A watercolour reproduced for the show is possibly a nude of Sarah Danby and it could be considered gratuitous. But Sarah was a singer and actress, and judging by the forthright pose, was perfectly happy about working with him.

Where does this leave us? As both curators insist, drawing conclusions from the works themselves can never be more than speculation. Like the crumpled sheets on an empty bed, which raise more intriguing questions than answers.

But the work does show how, although Turner never sacrificed his art for the “rubbish” of marriage, he did manage to find a lady – or two – to keep his bed warm.

Between the Sheets is at Turner’s House, Twickenham, until October 30, Monday to Sunday 10am to 4pm

Richard Holledge writes about the visual arts for the Wall Street Journal, Gulf

News, FT and the New European