Most of you have probably never been to Heligoland – the only German island in the high seas, about 70km off the mainland. Yet the fact that you can hop on a boat from Cuxhaven or Hamburg for a day trip to go birding, marvel at the famous Lange Anna (Tall Anna – a dramatic 154ft red rock column) or stock up on VAT-free goods is something of a miracle.

Eighty years ago, Heligoland was nearly wiped off the map.

Admittedly, it had already taken a hit in 1720, when a fierce New Year’s Eve storm split what was once one island into two. But in April 1945, it was 1,000 British bombers that pretty much reduced it to red rubble.

Helgoland, as Germans call it, had been turned into a fortress by the Nazis – a heavily armed outpost in the North Sea, the first to spot incoming aircraft. They had expanded first world war military installations, digging into the red sandstone until the island resembled a Swiss cheese: 13.8km of bunker passages in just 0.7sq km. Beneath the surface, there was space for 4,000 soldiers, supplies, and even an underground hospital.

Most of the 2,000-odd civilians survived the April bombing in a civil defence bunker. But the island was then evacuated under British control.

Two years later came the “Big Bang”: the British army blew up the remaining military gear with 7,600 tonnes of explosives. And until 1952, the RAF then used the uninhabited rock as a bombing practice range. It might still be one today, if not for the most peaceful invasion in German history.

In 1950, while the young Federal Republic argued about re-armament, two students from Heidelberg decided to make a statement for peace. Just before Christmas, they went to see the district administrator responsible for Heligoland. “Herr Landrat,” one of them told him, “we’re going to Heligoland next week to bring it back to you.”

The Landrat was not amused: “I’ve been negotiating about Heligoland for three years. Don’t mess this up – go back to Heidelberg!”

They chartered a fishing boat instead, took two journalists along for the ride, and landed on the island. British soldiers told them to leave before evening – the bombing would resume. But they stayed. A historic photo shows them in front of an old flak tower, raising the German and the European flag.

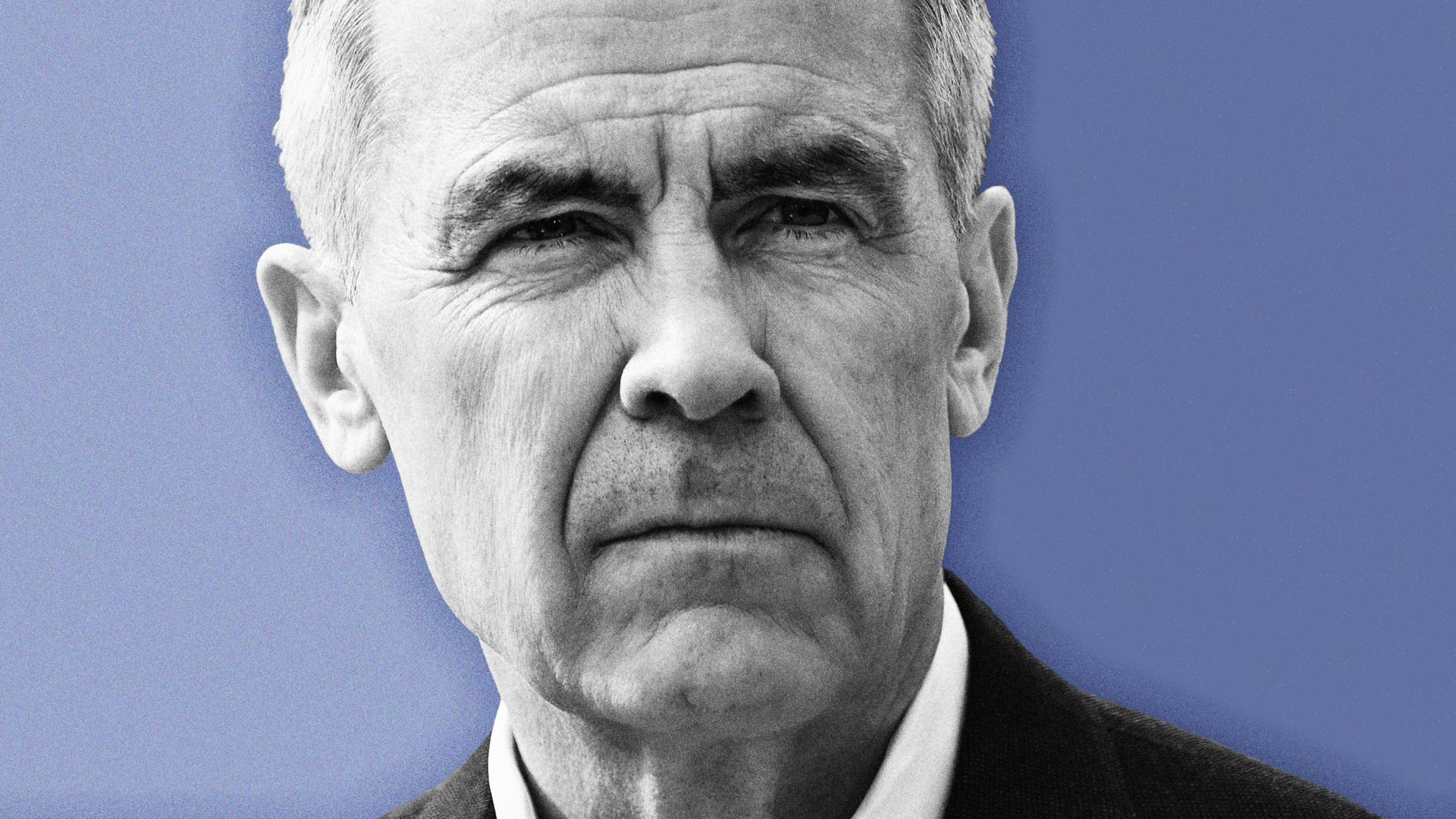

Their inspiration? Heidelberg professor Hubertus Prinz von Löwenstein – son of a British mother, and an early opponent of Hitler. Löwenstein had fled Germany in 1933 and campaigned against Nazism in the US. When he declared Heligoland’s use as a bombing range to be a breach of international law, people listened.

His visit to the island just before New Year drew international media attention. He was quick to stress this wasn’t about nationalism, but European unity. If the Heligoland issue could be resolved, he argued, nothing would stand in the way of British-German relations.

Historians still debate how much influence this “invasion” really had. The UK Foreign Office and Downing Street had long wanted to return Heligoland, acknowledging its symbolic value. But the RAF clung to their bombing range.

In the end, cold war logic probably won out, meaning a push to find incentives for West German society to identify with the western bloc: in February 1951, prime minister Clement Attlee announced the island would be returned within a year and the original inhabitants moved back in March 1952 to rebuild their cratered home.

But here’s the twist: for most of its history, Heligoland wasn’t German at all. The Frisian-speaking Helgoländer didn’t much care who claimed them: they belonged to the Duchy of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf, then Denmark, and in the 19th century, Britain – serving the empire as a smugglers’ paradise during Napoleon’s blockade.

So why the German fuss? Tourism, mostly.

In 1841, during a seaside stay, the poet August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben scribbled the lyrics to what is now the German national anthem, the Deutschlandlied. The island’s free-speech atmosphere attracted writers and scholars who were dreaming of a united Germany but were suppressed in their various duchies and princedoms.

It was only in 1890 that Britain officially handed the island over to Germany as part of the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty.

Today, Heligoland relies more on offshore wind-farm crews than tourists. But it’s still well worth the trip. The islanders are famously peaceful and forgiving – probably because with just 1,200 of them, holding grudges would be logistically tricky.