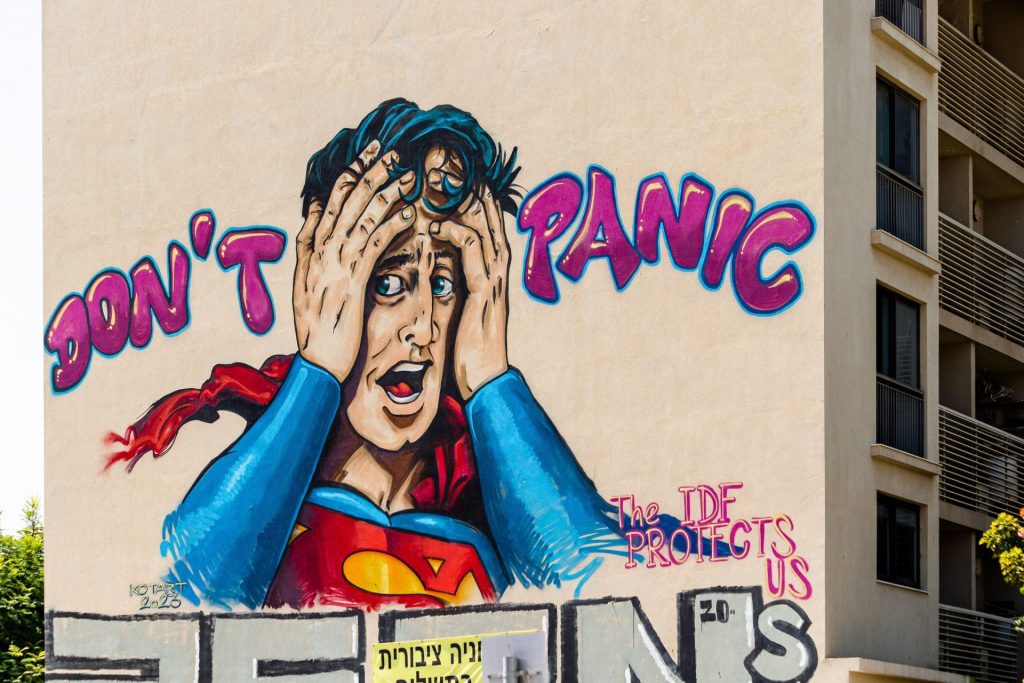

Superman is worried. In Florentin, a district in southern Tel Aviv near Jaffa, larger-than-life graffiti shows the superhero in red and blue, anxiously pulling his hair on the facade of an apartment building. The purple letters on the wall declare: “DON’T PANIC”, with smaller text adding: “The IDF protects us.”

Yet last year, when three artists created this illegal piece of guerrilla art overnight, they knew that on October 7, the Israel Defense Forces had failed to protect their country.

Nearly a year later, the collective trauma of that attack is still palpable. In Israel, social connections don’t follow six degrees of separation – it’s closer to zero. Everyone knows someone who was affected; victims, wounded, hostages, or their families. Friendships have been shattered, too.

That trauma is foremost in minds here. Then there’s the local and global criticism of the ever-rising death toll and devastation in Gaza.

Eighty kilometres away from the war, in Tel Aviv, people play matkot – paddle ball – on Gordon beach. But the rhythmic wooden sound, the clouds of weed that hang over the surf instructors and the scantily dressed Gen-Zs sipping cocktails in Neve Tzedek’s bars cannot obscure the fact that the country’s soul is at a loss.

There’s an uncertainty tinged with anger, a sense of betrayal, fear and despair, fuelled by ever-more devastating news – such as the killing of six Israeli hostages, murdered in a Gaza tunnel only last month. The notion that Israel could “buy peace” if Palestinians prospered economically is now shattered. The relative sense of security has collapsed.

Many Israelis grew up with their parents’ childhood recollections of hiding in closets to escape the Nazis. They thought it could never happen again. Then they were confronted with stories of Jewish children hiding in closets, in 2023. The horror of the unprecedented massacre, proudly presented by jihadi livestream, has a firm grip on the Israeli psyche. Yet alongside the war in Gaza, there is a second fight going on – one for liberal democracy.

“If there is an existential threat to our country this time, it’s not Hamas taking over, not Iran throwing the bomb – but that our country will not be the same place it used to be. Many of us feel that Israel will never be the same again,” says Ilana Dayan, one of Israel’s leading investigative journalists. She sits across the table at a cafe near her Channel 12 offices in northern Tel Aviv.

“On October 7, the state disappeared,” the 60-year-old tells me. “It will take us decades to understand it, what really happened, who was responsible for the military fiasco, the intelligence fiasco, the failure of our leadership.” She pauses. “But what is unforgivable is the absence of the state ever since October 8. The sense that there’s a government which has no executive capabilities, some would say: just a coalition serving its own interests.”

A public official, off the record, is more blunt: “We are led by a bunch of corrupted, inefficient scumbags,” he says. Israelis watch in shock as government decisions are dictated by minority interests, coming in two flavours: from the ultra-Orthodox, anxious to preserve both their right not to be conscripted into the army and also their social welfare privileges; and from the ultra-nationalists, who are aggressively pushing to expand Israeli-Jewish control in the West Bank. Prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu believes Israel can’t do without him, and Netanyahu can’t stay in power without the ultras.

In a three-page rant, he once called Dayan, who hosts the prestigious TV programme Uvda (Fact), a “left wing extremist” without an “iota of professional integrity”. After receiving the letter, she read it out on air, in full, for six minutes. That was in 2016. They have not become friends since.

Netanyahu – who will soon have to testify in his own corruption trial – hasn’t many friends left. “Bibi”, as he is generally known, is seen as the first prime minister since 1948 who doesn’t act in the national interest, but rather in his own. For that reason “Bibism” is in stark decline – but inside the Knesset, his coalition government still holds a five-vote majority.

Society doesn’t rely on politics any more, but on the roughly 300,000 Israeli men and women “in reserve”, which means they go in and out of active military duty. Dani, who asks me not to use his real name, is one of these reservists. He works at an IT startup near Haifa, an hour north of Tel Aviv.

Driving there is tricky because the blue dot on Google Maps insists it is currently in Beirut. “Spoofing”, interfering with GPS systems to distort their positioning ability, is something Israel doesn’t comment on. Airlines criticise the practice, but Israelis prefer analogue road signs over guided missiles blasting the port of Haifa. It’s just one of many trade-offs in this country.

Dani votes for left wing parties, and when he talks about the current government, his lean features harden: “I expect political leadership to have a vision. But there is none. No vision, no leadership.”

To him, Itamar Ben-Gvir, the far right minister of national security, is “a criminal! A racist agitator, convicted many times. That’s why he was never drafted. We don’t want his kind in the army. But now the man is in charge of the police.”

As for Netanyahu? Dani is no fan, but he wonders: “The protesters, do they really have someone better or do they just want to get rid of him?”

He’s referring to the hundreds of thousands of demonstrators who gather across Israel every Saturday. Originally, the protests were in reaction to proposed judicial reforms, which would have left government decisions unchecked. Now, people are demanding a hostage deal and early elections, in that order.

One evening, in the sticky heat of Tel Aviv, I join them in their field of flags on Kaplan Street. The protesters have reclaimed the Star of David – they refuse to let nationalists monopolise the Israeli flag.

Posters of Netanyahu with the words “Liar”, “Deserter”, “Corrupt” are everywhere. There’s merch, too: T-shirts with slogans such as “Our Shtetl is on fire” and “DEMOCRACY. Established 1948”.

When the crowd reaches Dizengoff Square, one protester points his megaphone at the diners in a restaurant. “Bon appétit,” he roars. “Don’t join us, let the government draft you and send you to Gaza.”

Dani, who commands more than 200 soldiers, has known Gaza since the 1990s. He remembers going on patrol with colleagues from the Palestinian Authority (PA). Until things got bad. Now, as a reservist, he’s regularly back in uniform.

Although he is not in combat, he insists that “we work incredibly hard not to harm civilians, despite Hamas using them all as human shields”. Otherwise, he claims, the death toll would be so much higher. “But people abroad shout ‘genocide’ anyway. You see, if we went in full force, at least we would get the job done,” he adds, aware that crushing the terrorists means no hostage would survive.

For Israeli society, this isn’t an option. The yellow ribbons, the “Bring Them Home Now!” banners, the photographs of victims and hostages are omnipresent, on motorway bridges, shop windows, bumper stickers.

Polls show that a majority of Israelis want Hamas destroyed. But more importantly, they want the hostages home.

The military establishment, too, prioritises a deal over Netanyahu’s red lines. The chief of staff, the minister of defence, the chiefs of Shin Bet and Mossad, Israel’s intelligence agencies, agree they will find a way to finish off Hamas once the hostages are free. This infuriates Bezalel Smotrich, the far right finance minister, who barks that the military must “stop preaching” and should “go on fighting and killing”.

Dani is driven by something else. “Everyone I know in the IDF feels guilty, to some extent. I certainly do.” He seems haunted by the idea that October 7 could have been prevented if they had not left unfinished business.

“Every time we had to fight in Gaza, we knew we didn’t destroy Hamas. We knew that at some point we would have to go in again.”

When I mention this to Dayan, her tone fills with sarcasm, as she recalls the code names of the various offensives launched against Gaza. “Yes, after every round in Gaza since Hamas had taken over – ‘Hot Winter’, ‘Cast Lead’, ‘Breaking Dawn’, ‘Protective Edge’, they have very sexy names – the leadership told us: ‘We smashed Hamas, we hit Hamas, Hamas will never be the same’. That was nonsense.”

In reality, Netanyahu’s counterproductive policies weakened the more moderate Palestinian Authority, which controls the West Bank, while Hamas grew stronger in the Gaza Strip, helped by money from Qatar. Netanyahu’s attempt to manage this situation instead of trying to solve it backfired horribly.

“That’s another story,” says Dayan, the veteran journalist, “and an important one. The deeper story, however, is that our kids wanted to live life. We wanted them to live life. To create a startup, go to Berkeley, rent a place in Tel Aviv, have a family – we wanted to convince ourselves that we are a normal place. And when you walk the streets of Tel Aviv, you are fooled into thinking we really are.”

Dayan has three children and became a grandmother this year. “But when my daughter sends me a photo of her newly born son,” she says, “I know there’s a chance someday that my son-in-law will have to put it on the inside of a tank. We all know that he will have to serve in the military again. And so we live this ambivalence.”

Her son Gonen, a trumpeter, just graduated from the Barenboim-Said Academy in Berlin, with classmates from Lebanon, Syria, Gaza and Tehran. “The tensions are there, but so is the friendship and the love of music.” She was moved to tears. “When these friends rooted for Gonen at the end of his graduation recital, their applause was like a moment of grace in a world of misery and pain.”

My phone buzzes, “Hostile aircraft intrusion: Upper Galilee (30 seconds)”. A red alert, not for Tel Aviv though; alarms here are rare, whereas in the Gaza Envelope and the north, dozens of towns and villages are still evacuated.

Those still living there have to go to the shelter on a near-daily basis since October 8, usually a stairwell. It’s a great way to meet new neighbours, people joke.

In Tel Aviv, the rule of thumb is that you have 90 seconds to find cover. Elsewhere, you have 30 or even 15 seconds. Unless the app says: “immediately”, like it did in late July on the Golan Heights, when 12 Druse children and teens were killed, presumably by an Iranian-made Hezbollah rocket. There was no time to flee from the football pitch.

Even before the most recent escalation, experts put the chances of avoiding war with Lebanon at 20%. Is another full-scale war really inevitable? Dayan shakes her head. “Nobody wants it,” she says, and that includes Hassan Nasrallah, the general-secretary of Hezbollah. “Israel would rather not go there now. The military is exhausted.” And the government? “I believe Netanyahu doesn’t want to cross this line,” she says. “He knows that it will be one war too many for Israelis. There’s only so much you can ask.”

Foregoing this option does of course bring other risks, in terms of deterrence. There are no textbook solutions. “This is what many countries in Europe don’t get,” Dayan says. “They don’t have to weigh these costs.”

Europe, from an Israeli perspective, doesn’t get many things. Parents who join anti-government protests on Saturdays are praying for their children who are currently serving in Gaza and sometimes cannot get in touch with them for weeks. University professors see A-grade students fall behind in class with signs of depression. Families are thinking of leaving the country. Many, in fact, do.

An elderly lady I talk to mentions her granddaughter, just out of school, who wants to fly fighter jets. “Have mercy on your parents, child,” she told the 18-year-old, who has three bothers who will also have to serve.

“We live in a terrible neighbourhood, in a disaster area, where the weak do not survive,” Dayan says. “And every now and again we have to defend our lives. But many of us make sure we know which kind of life we fight for, which kind of Israel we want to live in.”

The essence of “Israeliness”, as she explains it, is “being both humanists and fighters, defending our lives and our values.” The Hamas atrocities have made it infinitely harder for these values to be kept up. During the first weeks of the war, for instance, the horrors in Gaza weren’t properly covered by Israeli media.

“We were consumed with our own tragedy,” Dayan recalls. “Israelis had no place on their hard disk, no bandwidth, to encompass the suffering in Gaza. It is understandable, but not any more.”

The numbers of casualties are reported, of course. But, with the exception of Haaretz newspaper, “not the personal stories of people in Gaza,” she says.

When speaking to Israelis, I don’t encounter indifference towards the fate of Gaza. Nadav, whom I meet in Kfar Aza, is aware that the Palestinians who worked in the kibbutz and gave Hamas vital information about its security may have been forced to do so. That, maybe, they had no choice.

Around 750 people used to live in Kfar Aza – 61 were murdered, among them Nadav’s 23-year-old sister, Sivan, and her boyfriend, Naor. From the destroyed western part of the compound, you can see the fences to Gaza and hear the gunfire. Nadav only sighs: “Poor kids.”

There’s one question that I hear frequently: “They could have turned Gaza into a new Singapore, with all the money flowing in – why didn’t they?”

It’s not a question Udi Goren would ask. “In the past 15 years Israel has created a situation where Hamas is the largest employer, has access to all the resources, controls all the tunnels, the money. So if you are Gazan, either you join Hamas and you get a portion of the power, or you’re run over. We knew this was happening, when the Qatari money funnelled in.”

At the Hostages and Missing Families Forum, Goren calmly states that Netanyahu jeopardised a deal at least twice. “It could have happened. He made it not happen. But more and more people realise that these slogans – the ultimate victory, the absolute victory, whatever – are bogus. There is no victory in this war.” Only bringing back the hostages and working towards a better future seems like any sort of victory, because: “War will never keep us safe. And as long as the Palestinians have no alternative, they’ll keep turning to Hamas.”

Goren concedes that “the big tragedy of the Palestinian people is that they always had horrible leaders.” He still thinks it’s Israel’s responsibility to find a better option. But by now, as there isn’t really a history of peace-loving democracies in the vicinity, most Israelis either don’t support a two-state solution or simply don’t think it feasible in the foreseeable future.

To them, the sequence of events since the Oslo accords and Camp David – suicide bombers, the second intifada, Hamas rockets – is proof that compromise is rewarded with violence.

Hamas body-cams provided the ultimate proof of that, as the horrors of October 7 were recorded and broadcast by the attackers. Secular Jews, who a year ago couldn’t care less for West Bank settlements, look at the map today and basically see Tehran lurking on their border, and the prospect of October 7 reloaded.

Israel lost more than its deterrence on that day, it lost faith in a solution – and this may be Hamas’s most sustainable achievement. Yair Lapid, former prime minister and now the leader of the opposition, wouldn’t agree. Complicated, but doable, his eyes seem to say when we talk about the conflict.

Beyond the hostages’ safe return, his main concern is Iran, and preventing Tehran from becoming a nuclear power and regional hegemon, by partnering “with countries in the region who share the same threat as us – Iran”.

Gaza, to him, “is part of a bigger problem, so make it part of a bigger solution,” by working “with Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Bahrain, Egypt and the UAE to agree on a regional coalition to take control over Gaza, with a limited branch of the PA and create a 10-year plan with clear milestones.”

He doesn’t mean the current government, obviously. “They will lose the next election, and we have to make sure they never come back.”

Regarding the peace process – words that currently sound like science fiction – every government will have to deal with a society more convinced than ever of the dictum that “our kids are taught to live, theirs are taught to hate”.

Dayan explains: “My zionism is rooted in Jewish tragedy, but it is mindful of the tragedy of others as well. My zionism is the miracle of a national home for the Jewish people, but it remembers that the miracle of one can be the calamity of the other.”

Outside Israel, it has been turned into a slur. Yet, “zionism at its best was humble and doubtful,” Dayan says. “It recognised the contradiction of its being: the rebuilding of one nation, the fate of another. It embraces the rightfulness of our existence but rejects notions of overconfidence.”

To her, this means that “one cannot easily justify the occupation. Even if the prospect of a two-state solution sounds so fragile these days. Even if I am doubtful of Abu Mazen’s (Mahmoud Abbas’s) ability to deliver or of the Palestinian Authority to govern and even if Israel would have to take an amazingly crazy risk to agree to a two-state solution, a moral person will find it hard to justify a more than 60-year-long occupation.”

“That being said,” she continues, Hamas and October 7 are not about occupation. And the governments of Norway, Ireland, Spain or the students in Columbia University – they don’t seem to see Hamas for what it is…”

She recalls when she was in Kibbutz Be’eri, “six days later. The mattresses on children’s beds were still soaked with blood, the bodies were still mounted everywhere, we couldn’t breathe.”

Dayan speaks for many other Israelis when she says: “As critical as I am of Benjamin Netanyahu and my own government, those other governments and many of the protesters who are waging a propaganda campaign against Israel, they don’t differentiate.”

Of course Israel’s mistakes should be criticised, there’s also understandable criticism of its policies. But she adds: “The problem I have with the vicious criticism, whether it is antisemitic, anti-zionist or anti-Israel – it’s often a mixture – is that those people wouldn’t mind if the state of Israel ceased to exist.”

She pauses. “They don’t care. And to them I would say: I do care.”