Marcello Mastroianni and Jeanne Moreau are photographed walking across parkland. Trees on the horizon, wild flowers at their feet. He is looking down, pensive. She is head back and laughing.

Jeanne Moreau laughing! She rarely smiles, let alone laughs. Certainly not in Michelangelo Antonioni’s La Notte, the bleak 1960 film about a faltering marriage.

But here she is caught off guard and off set during a lull in filming by Sergio Strizzi (1931-2004), a photographer who worked on more than 100 films, including some of the most evocative and challenging of postwar Italy. An engaging exhibition at the Estorick Gallery in north London, Sergio Strizzi: The Perfect Moment, presents a selection of his work as a still photographer, curated by his daughters Vanessa and Melissa.

But choose your words carefully. As Italian director Ivan Cotroneo insists in the exhibition catalogue: “There is a vast difference between being a film-set photographer and a photographer on a film set. Strizzi was rather a visual artist who often happened to receive commissions to work on film sets.”

What commissions they were, and what a cast list. He became friends with directors such as Antonioni, Federico Fellini, Francesco Rosi, and later John Huston and Francis Ford Coppola. He earned the trust of Monica Vitti, Sophia Loren and Monica Belucci, photographed leading men from Gian Maria Volonté to comedy actor Tòto, stuffing spaghetti into his pockets (Poverty and Nobility) and often persuaded Mastroianni, always reluctant to pose for a camera, to glower in moody acquiescence.

Benigni and

Nicoletta Braschi

on the set of Life is

Beautiful, 1997

Malèna

Mastroianni and

Jeanne Moreau off

set while filming

La Notte, 1960,

by Michelangelo

Antonioni

But he did it his way. He recalled an “intense discussion” with René Clément on the set of This Angry Age, which starred Silvana Mangano and Anthony Perkins.

“He wanted me to photograph along the camera’s axis; I did what he asked me to do, then took some other shots that were more to my liking.” The result, free from the constraints of providing a publicity photo to appear on a cinema poster, is a cheery composition with Perkins and Mangano larking about, hoofing happily.

Strizzi was a self-taught photographer whose anarchist father fled fascist Italy at the start of the war leaving the boy, his mother and three siblings in poverty. He worked in a paint shop before doing odd jobs in a photo agency. One day he “borrowed” a camera and two rolls of film to take pictures of a model aircraft display. To his surprise and delight, one of his photographs appeared in a national newspaper. The agency’s owner was so impressed he gave him the camera – quite an improvement on the homemade camera he had been using, made of iron bellows and a wooden back – and said: “Have a walk, photograph whatever interests you.”

It was 1948. Only 17, he was on his way. He made a name for himself by taking the first photographs of a notorious criminal, Salvatore Giuliano, who had been shot dead by a treacherous accomplice, and soon was working for Carlo Ponti and Dino De Laurentiis on a football documentary, The Eleven Musketeers.

By the 1950s, postwar Italy was shrugging off the repressive years of fascist rule, eager for beauty, style and entertainment. It was la dolce vita and la bella figura all rolled into one heady mix. The film studios of Cinecittà, which had just reopened, were at its creative heart.

The films that emerged from this “Hollywood on the Tiber” embraced new studio production techniques, shooting on location, using natural lighting and, above all, addressing social, sexual and moral issues with a panache that had not been done before.

This was now Strizzi’s world – though he was convinced it was over before it had begun. During the filming of Vittorio De Sica’s Gold in Naples, a series of vignettes about that city’s unruly life, he bumped into a dolly and disrupted filming. De Sica shrugged, gave him one of his “dramatic looks” and said: “No problem, let’s do it again.”

Later, Strizzi shows him in the making of The Last Judgment, a flop of a film about the way people react to the end of the world, standing on steps in Naples gesticulating fiercely while the cast look on nervously.

He worked with Antonioni on three of the most seminal films of the era, L’Avventura, La Notte and L’Eclisse, and caught him sitting on the grass between takes, cooling off with ice cubes with Moreau during La Notte. Antonioni, who described Strizzi as “one of the best photographers in international cinema”, stares steadily at the camera. Moreau ignores it. Not a hint of a smile.

During the filming of the murder mystery Illustrious Corpses he turned the camera away from the set on to the director, Francesco Rosi. He’s wearing a flat hat and sunglasses, and he’s giving his instructions with a sequence of hand gestures as complex and passionate as Leonard Bernstein conducting Mahler’s 2nd Symphony.

Strizzi later reflected: “When you take a photograph, you have to wait for the right moment or create a situation. You wait for a gesture, a particular moment, and a dialogue can be sparked by that gesture, by that moment. If the light is wrong, I’ll wait.”

He made the point forcibly in 1990 during the filming of The Godfather III, when he walked off the set without pay because the director of photography, Gordon Willis, wouldn’t give him time to take the pictures he wanted.

He did, however, capture a whimsical aside of the director, Francis Ford Coppola, standing thoughtfully in a courtyard watching a flock of pigeons as they flap and coo.

As one might expect, the men smoulder, square jawed, keen eyed, like Yves Montand in Men and Wolves, Al Pacino, slightly quizzical as if he had been caught off guard, and Alain Delon entangled with Monica Vitti in L’Eclisse. Sex symbols all, but one of the most appealing is of Roberto Benigni – no heartthrob – and Nicoletta Braschi on the set of Life is Beautiful, the unbearably poignant evocation of a family struggling to survive in a Nazi concentration camp. “I really love him,” said Strizzi, and it shows. The pair are looking up at the cameraman quizzically as if to ask what they should be doing next. It feels spontaneous, unrehearsed.

And what of the women? After all, Hollywood on the Tiber produced some of the most charismatic actresses of the day – and today, for that matter. Strizzi took Vitti away from the film set for a shoot on one of Milan’s tallest skyscrapers. Glamorous, of course, downright sultry, but always stylish.

Cotroneo writes that Strizzi’s portraits of female stars were not “straightforward… but represent moments of understanding – and sometimes of seduction – between the eye of the camera and that of the diva.”

Sophia Loren in The River Girl, in which she plays a betrayed peasant girl who seeks revenge but achieves some kind of redemption, is staring challengingly at the camera, tugging at her rope belt defiantly. Apparently she and Strizzi would play a game to see who could out-stare the other. He even cheated by reflecting the light from a mirror into her face. She didn’t blink.

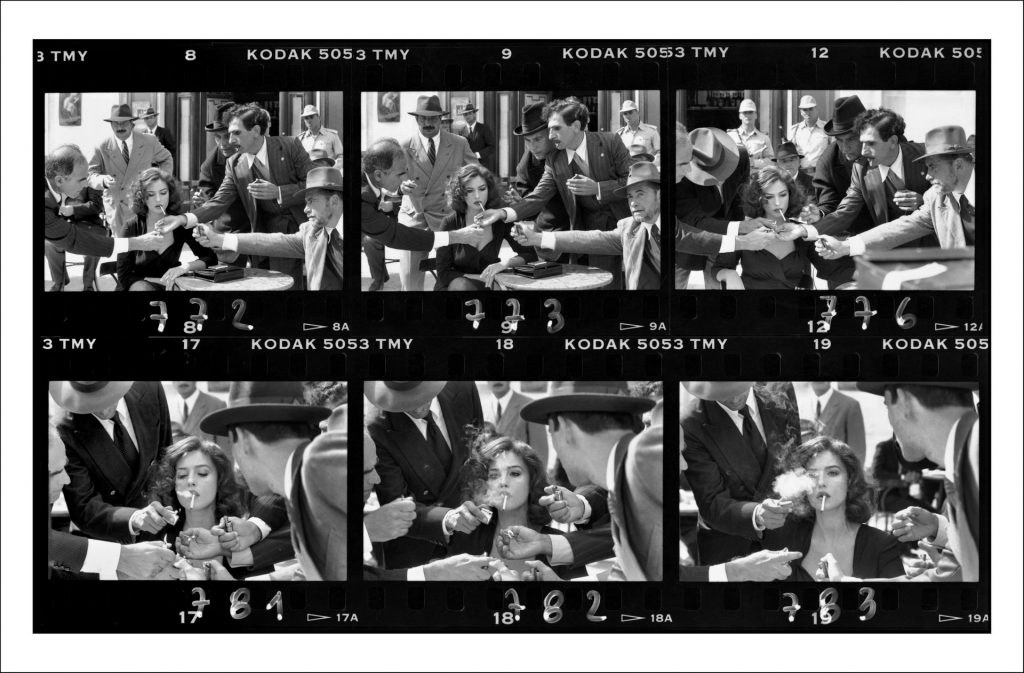

Monica Bellucci appears topless in one photo from Malèna, gazing boldly at the camera, but in an unsettling sequence of shots Strizzi represents her surrounded by a posse of men leaning towards her to light a cigarette. It’s unsettling because she is playing an abandoned wife who is forced to become a prostitute. She is there to be exploited. But as the camera shows, her gaze is unflinching. The men might think they are in control, but not so: it’s Malèna.

There are few more beautiful images than that of Sylvana Mangana in The Last Judgment looking down and away from the light behind her, which glances off her glittering gown and casts an enchanting shadow on her face. It was a picture that had lain lost in a drawer for years until Vanessa chanced on it when she was going through her father’s thousands of unpublished photographs.

“Oh I forgot,” he said.

Most of the photos are close-ups, but when the camera pulls away it reveals just how precisely and evocatively Strizzi composed his work, in a way that reveals so much more about film-making than a still photo could ever achieve.

A bunch of extras hang around the camera in The Great War. Some slump wearily, they’ve had enough. An aerial view of a dance scene, the finale of The Last Judgment is a marvel of floaty ball gowns and men in dinner jackets; in The Legend of 1900, directed by Giuseppe Tornatore, the entire set, the cameras, the cast, the crew, the host of extras are brought together in one wide shot.

For all his success, he took many years to be convinced that others really rated his work.

Vanessa and Melissa recall the day Sean Connery and the directors of You Only Live Twice gathered to check out the first prints of the shoot. Strizzi, who barely spoke a word of English, thought they were rubbishing his work. Mortified, he exclaimed to his wife: “I’m leaving. I told you the photos were bad.”

“They weren’t saying they were terrible,” she explained. “They were saying they were terrific.”

Sergio Strizzi: The Perfect Moment is at the Estorick Gallery in London until September 8