Early on Thursday morning, as Spaniards in bars across the country tucked into their tostadas and café con leche, the tiny wall-mounted TV sets were filled with flustered-looking broadcasters reporting that a last-minute deal had been made between the Socialists and Catalan separatists.

A few hours later, as the results of a vote were read out beneath the domes of Spain’s elegant, horseshoe-shaped Congress of Deputies, a wave of applause rippled across the wooden benches. The left-hand side of the chamber rose to its feet and Pedro Sánchez, Spain’s acting Socialist prime minister and leader of the PSOE, turned and smiled, visibly relieved, to congratulate a woman sitting directly behind him.

Who was he congratulating? Francina Armengol, the newly elected speaker of the Spanish Congress and, crucially, the PSOE candidate. Sánchez leaned over and embraced Armengol with a customary Spanish double kiss. The PSOE took a big step towards securing re-election after Armengol was elected with an absolute majority, indicating that Spain’s left wing block could have the numbers to win a crucial vote and form a government.

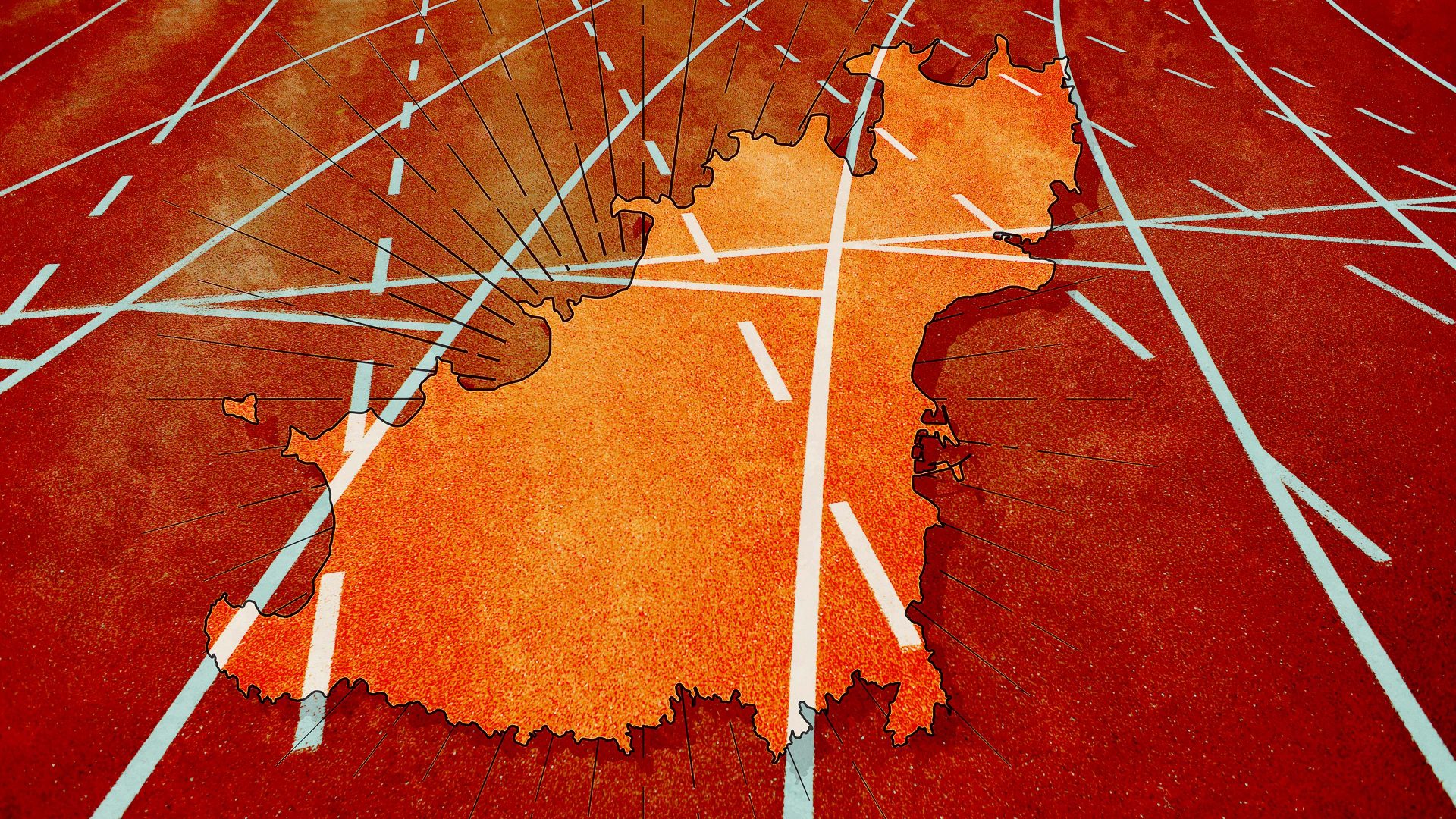

It is far from inevitable, however. The uneasy coalition cobbled together by the PSOE in order to win the vote shows that Spain’s regional parties, particularly Catalan separatists, now control the fate of any prospective national government. July’s general election failed to provide any party with a governable majority, and another election later in the year is still plausible if negotiations break down.

Armengol, a Catalan speaker and the former regional president of the Balearic Islands, was elected with 178 votes (out of 350) after the Catalan separatist party Junts per Catalunya backed her candidacy. Following the result, Armengol said the vote “marks a path” to government.

It also revealed deteriorating relationships on the Spanish right. Cuca Gamarra, the right wing Partido Popular’s (PP) pick for speaker, won only 139 votes after the far-right Vox Party shunned the PP and backed its own candidate. As the left of the chamber smiled and celebrated, Gamarra sat sullenly, her jaw tense. The PP and Vox govern together in several regional coalitions across Spain following sweeping gains in May’s local elections, but relations are now chilly.

Spain’s regional parties have been elevated to political kingmakers at the national level. In Congress, as members edged along in single file to vote for the position of speaker, Gabriel Rufián, the young, underdressed Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC) spokesman, confidently held his aloft.

That’s why the PSOE’s choice to nominate Armengol was widely seen as a nod to Catalan and other regional parties. Sánchez understands that he needs to court these regional groups in order to govern. Earlier in the week he pledged to support a bid for Spain’s regional languages to become official languages in the EU, to try to placate members of the Junts party.

The leader is Carles Puigdemont, the former president of Catalonia who led a failed independence bid in 2017 and fled to Belgium to avoid arrest. In return for its support of the Sánchez government, Junts has demanded another independence referendum and a legal amnesty for the leaders of its attempted secession. Sitting together on the Congress benches as the votes were counted, Junts deputies seemed relaxed, confident, laughing and smiling among themselves.

But the PSOE has made clear that it would not grant a referendum. As Junts is unlikely to back a right wing government, a compromise seems inevitable. That will probably include the use of the Catalan language in the Spanish Congress and an investigation into whether Pegasus spy software was used to snoop on Catalan leaders.

Sánchez knows that relying on Catalan separatists is controversial and a risk. But he is a political gambler by nature – if he hadn’t dared to call the snap election on the back of bruising local election results, he would not now be on the verge of securing another term in office.

Last Thursday’s vote was a small victory for the left; one step closer to government. But herein lies the paradox of Spanish politics today: in order to form a national government, Sánchez will be forced to rely on separatist groups that don’t want to be part of Spain.