It was going to be the year Miguel Induráin completed the road from champion to legend. Having done the notoriously tough Giro d’Italia-Tour De France double in 1992 and 1993, the mighty Spaniard looked a dead cert for the “threepeat” in 1994. Not even Eddy Merckx, the only three-time double-winner, had gone back-to-back-to-back.

But the man whose sturdy 6-foot-1, 12 stone build had earned him the nickname Big Mig was about to meet an unlikely nemesis: a short Italian chap with thinning hair and a physique that suggested he was badly in need of a meal or three.

Induráin’s patented path to victory was to blow the competition away in the time trials and then to grind it out in the mountains. Yet on June 4, in the race’s 15th stage, Marco Pantani shattered his plans, shattered his aura of invincibility, shattered him even as a man.

When the 24-year-old Pantani broke away near the bottom of the Mortirolo Pass, it seemed only a matter of time before Induráin reeled him in. After all, this was a brutal near-13km climb into the Italian Alps, the gradient of which averages almost 11%. Passage is made tougher still by 33 hairpin turns.

Yet the steeper the incline became, the higher Pantani rode out of his saddle. Decades later, Sir Bradley Wiggins, one of his biggest fans, marvelled: “Marco personified how climbing mountains should look. This floating, angelic sense… it seemed almost effortless.”

While Pantani glided up the hillside, the 29-year-old Induráin wilted. So did race leader Evgeni Berzin. This was astonishing stuff, watched by more than six million Italians on TV. Pantani’s speed on the climb was 16.954km per hour, destroying the previous record of 15.595km per hour set by Franco Chioccioli three years earlier.

Next came the final ascent of the day, the Santa Cristina. Induráin had passed Berzin on the Mortirolo descent, but the man in the pink jersey was now leading a frantic chasing group. In order to impede Berzin’s progress, Pantani chose to wait for Induráin in the valley and the Spaniard summoned all his reserves of strength, moving at a pace designed to dissuade the young interloper from attacking. For a few moments at the start of the ascent, this unlikely-looking pair of rivals raced side by side.

Then Pantani turned on the afterburners. Something inside Induráin broke as he watched the younger man stream away. The champion was passed by two other riders and trailed in 3:30 behind. Berzin did even worse, at 4:06. “Marco had an extra gear on the climbs,” Berzin said later. “He just threw caution to the wind”.

Marco Pantani would not win the Giro for another four years but on that afternoon, everyone knew that he would win one day. Cycling had a new superstar.

The crest of the continent’s most celebrated climbs were a way away from the port city of Cesenatico, where Pantani was born in 1970. Like many of the local boys, the kid nicknamed “Elefantino” (The Little Elephant) on account of his prominent ears would join the Fausto Coppi cycling club. His first time riding with his friends was particularly memorable as Marco’s father Paolo Pantani recalled, “He took his mother’s bike… His feet barely touched the ground”

Despite this handicap, the young Marco kept up with his teammates on their racing models. And come the day’s end, a situation emerged that prefigured his future success. Paolo remembered: “About three kms from home there was a road bridge,” continues Paolo. “As the boys began to climb, Marco stood up on the pedals… and overtook them all!”

Pantani’s childhood mirrored his encounter with Induráin. As classmates and friends grew taller and filled out, he resolutely failed to follow suit. When he entered his first adult race, he weighed all of nine stone soaking wet. He was furious whenever he was listed at 5ft 7in, insisting he was 5ft 7½. Disadvantaged though he appeared, Marco Pantani was in fact perfectly proportioned to rule the mountain stages of the grand tours.

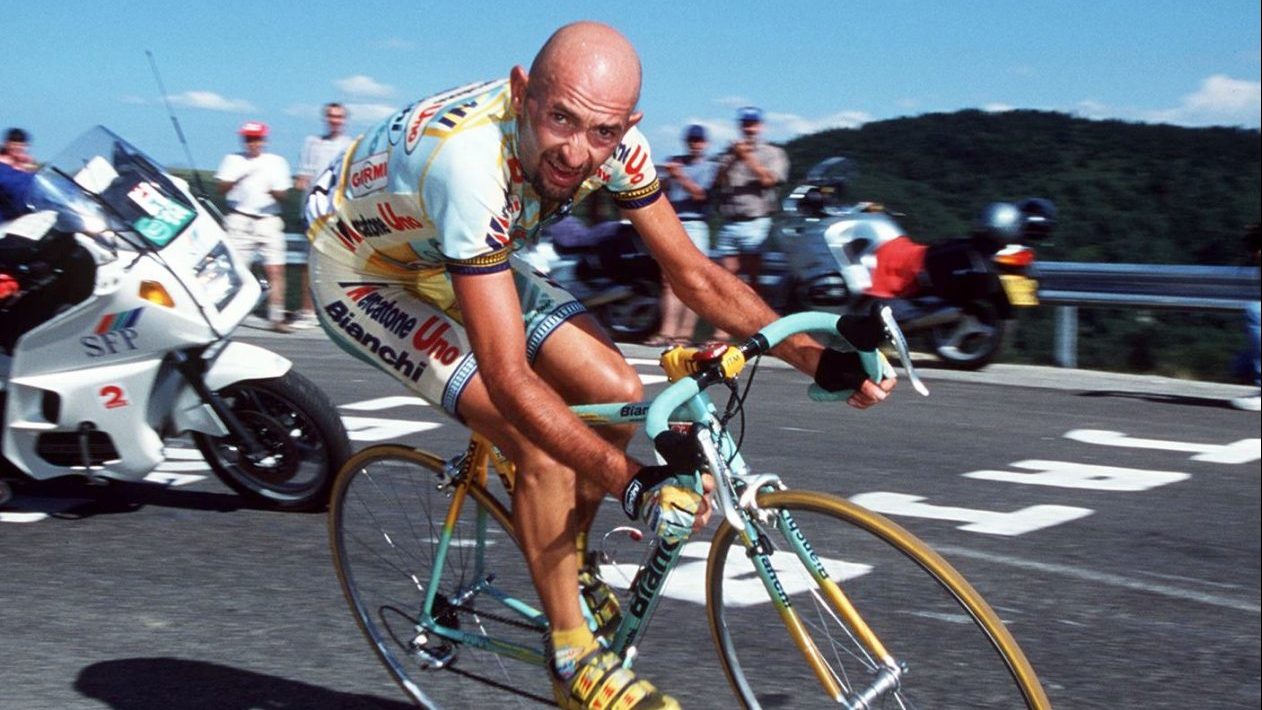

In 1998, Pantani’s perfect climbing physique saw him become only the seventh rider to complete the Giro-Tour double, the latter featuring another memorable 15th stage in which he took apart the fearsome Jan Ullrich using the same casual force with which he had broken Induráin four years earlier. By now, Pantani was known the world over as “Il Pirata” (The Pirate) thanks to his having decided to go bald on his own terms before embellishing the look with an earring, a tattoo, a bandana and a goatee.

The nickname could just as easily have been down to his swashbuckling approach to his craft. At a time when cyclists had begun to resemble machines, Pantani was almost impossibly human, unable to conceal his emotions – spectators saw him screaming with agonised determination during punishing climbs – or his passion for riding. Fans loved his idiosyncrasies; his refusal to wear a helmet, his love of Nutella and karaoke.

Soon though, Marco Pantani faced a mountain not even he could get over. In an era when drugs were rife in world cycling, he was forced to withdraw from the 1999 Giro on account of raised haematocrit levels – a possible indication of blood doping.

The Pirate, who valued his authenticity above all else, spent the rest of his life battling back claims that he was somehow a fake. In one of his last interviews, Pantani was on the brink of tears when he said, “Cycling started as a game – the joy of testing myself against other boys my age. In time it became a job… I’ve been pressured. I’ve been humiliated. Today, I don’t associate cycling with winning. I associate it with terrible, terrible things.”

A failed relationship only exacerbating his depression, Pantani sought refuge from his misery in a hotel room in Rimini, a large quantity of cocaine his only real company. It was with an excess of this drug in his system that Marco Pantani would be found dead on Valentine’s Day, 2004. He’d turned 34 the previous month.

Cycling, and the whole of Italy mourned a slight figure who had fought his way up the continent’s most celebrated climbs like an Ibex, only to then descend with the speed of a falcon. Rarely have a man’s gifts better reflected the span of their life, one that has been celebrated in movies, documentaries, an ever-growing number of biographies, even a graphic novel. Monuments to him can be found in Cesenatico, on the Alpine passes of Colle Fauniera and the Col du Galibier and of course on the Mortirolo.

The man that Marco Pantani took apart on June 4, 1994, remains in awe of him. He was, said Induráin, a “tragic genius… there may be riders who have achieved more than him, but they never succeeded in drawing in the fans like he did.”

Home is The Pirate, home from the sea.