“Love is dark and complicated.” So said Andrew Scott while promoting his recent film All Of Us Strangers. And he’s right – love can be scary, overpowering, even baffling. Not that you’d know it from most of the films we watch.

With some notable exceptions, the complexities of movie love don’t extend far beyond “first they hate each other, now they love each other”. Rom-coms are as far away from our real-world experience as much of the violence that is found in film.

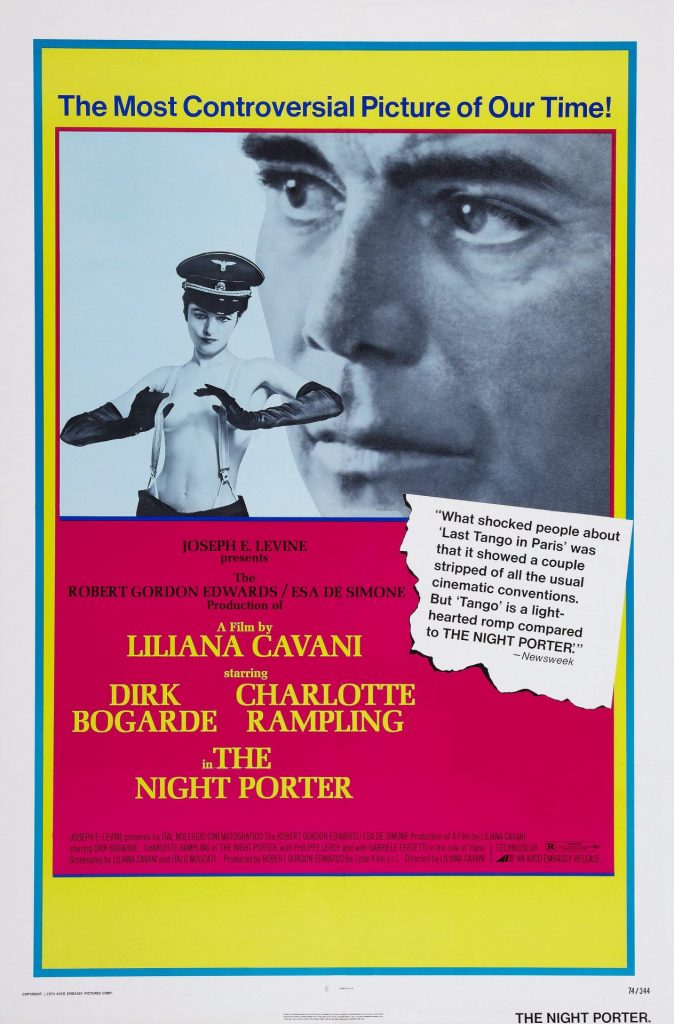

All the more reason then that, when something like Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter comes along, audiences don’t know how to respond to it. Neither do critics, or movie buffs.

Some find this story of the love affair between a former SS commandant and his former captive difficult but honest and authentic in its detailing of the perversity and strangeness of human emotions.

Others agree with the New York Times, which on its release 50 years ago called The Night Porter a “portrait of abuse” for “painbuffs” only, charging it with being “romantic about abuse… The anguish of the prisoners in the camps is exploited simply for the sake of sensationalism.”

When it won a Criterion Collection release in 2000, rubber-stamping it as a modern classic, the academic and author Annette Insdorf conceded that while the film “can be seen as an exercise in perversion and exploitation of the Holocaust” it was to be praised for its “psychological continuity of characters locked into compulsive repetition of the past”.

Set in Vienna in 1957, The Night Porter stars Dirk Bogarde as Maximilian Theo Aldorfer, whose nocturnal hotel work extends to pimping and administering illegal substances. These extracurricular activities conflict with Max’s outward image of respectability.

Max, however, hasn’t always been a night porter. During the second world war, we discover, he was an SS officer who used his position as a concentration camp medic to exploit the female captives.

One such woman is Lucia (Charlotte Rampling), the daughter of a socialist politician whose subsequent relationship with Max would challenge most people’s understanding of taboo. Now in the 1950s, Lucia is touring Europe with her American husband when she walks into Max’s place of work.

Within no time at all, the pair are back at each other and with each other. That their relationship makes sense to one another is hard to dispute.

Less understanding are Max’s former Nazi friends, all of whom are living anonymous lives in Austria. Might Max’s obsession lead to their capture, trial and imprisonment? It’s a chance the ex-SS officers aren’t willing to take…

As outlandish and distasteful as all this sounds, it’s worth remembering that The Night Porter has a strong basis in fact. Before she embarked on a career in feature films, Cavani was an award-winning documentary maker, her work including History of the Third Reich, the first attempt by a director from the axis powers to get to grips with the horror wrought by Hitler.

During her preparation for the film, Cavani sat down with a woman who had spent years in captivity, during which time her safety was guaranteed by a camp commandant with whom she became involved sexually.

From this, Cavani and her co-writer, Italo Moscati, wove a story that caught the attention of British actors Dirk Bogarde and Charlotte Rampling. Having previously addressed 1930s National Socialism in Luchino Visconti’s The Damned (1969), the pair now prepared themselves to explore the aftermath of war and the idiosyncrasies of love.

“I certainly didn’t have a sadomasochistic story in mind,” Cavani says in the 2019 documentary Fascism On A Thread: The Strange Story Of Nazisploitation Cinema. “We never even considered that term.

“We wanted to tell the story of an ex-Nazi and an ex-concentration camp inmate. Each of them comes from a totally different world. It’s a story which in part resembles stories and descriptions I heard from concentration camp survivors that I interviewed. Those experiences had left a permanent mark on those victims’ memories which will never be forgotten.”

Moscati told the documentary makers: “The idea was of centering the story around two characters who meet again after the end of the long and tragic era of Nazism – there are no more concentration camps, there are no more extermination camps. There is a strange sense of solidarity that develops between the executioner and his victim. This created a lot of discussion.

“The film basically shows the long-term effects of Nazism. It could also be used as a metaphor for things on a wider scale of humanity. Things often aren’t as neat and clean as they appear on the outside. Darkness exists.”

The challenge of playing Max was one Bogarde relished. A very long way from the light comedy of the Doctor series, the actor dedicated the last act of his career to making a different kind of film with a new breed of director.

As he explained to Barry Norman in 1974, “I believe a film should disturb an audience, not just pleasure it, amuse it – I’ve done all that. Now I want to make pictures that disturb you and make you talk… And that’s why I prefer to work with Cavani, with Louis Malle… with Visconti, because there’s a kind of experiment going on. It’s very exciting.”

Not only is The Night Porter exciting, parts of it are also undeniably erotic. The sequence in which Rampling’s Lucia performs Marlene Dietrich’s If I Could Make A Wish for her captors in an SS cap and not much else, recalling Salome, is among the most memorable in 1970s film. But with her audience in dress uniform and Bogarde’s Max showing his appreciation for the turn not with a bouquet but with the severed head of a male prisoner who had been abusing Lucia, it’s also seething with horror.

This scene – our collective memory of which seems to have merged with a Helmut Newton nude shoot that Rampling posed for the previous year – is but one of many that causes the viewer to flinch. When prisoner and captor recommence their sexual relationship, Cavani captures everything in one long, agonising take. It’s undeniably cinematic. It’s also profoundly troubling.

So troubling, in fact, that when The Night Porter arrived in America, critics such as Vincent Canby, Pauline Kael and Roger Ebert rushed to say the worst possible thing about Cavani’s picture. Kael won the day with her remark that “[The Night Porter] was directed by a woman, which proves no more than that women can make junk as well as men.”

The European critics weren’t quite so unkind, but still seemed unsure of what to make of the picture. This is perfectly understandable, what with the movie addressing subjects that only a few years later became the selling points of many a video nasty.

Yet The Night Porter is very much not to be put in the same bracket as Ilsa – She-Wolf Of The SS. For one thing, it’s beautifully shot, with Alfio Contini filming the flashbacks in sickly greys while capturing modern-day Vienna in rich, warm autumnal hues.

It also acknowledges the Austrian capital’s previous dalliances with film – at one point in an antique shop, Rampling absently-mindedly strums a zither, the instrument that provided The Third Man with its distinctive soundtrack. Of course, in Carol Reed’s film, Venice was strewn with rubble. In The Night Porter there is no rubble apart from the broken rocks of humanity.

For further evidence of intelligence, look no further than the way The Night Porter openly addresses that which might be held against it. In another film, it would be too on the nose to outright explain the title character’s choice of profession. But in a picture that some would describe as shameless there is merit in Max’s confession that, “I have a reason for working at night. It’s the light. I have a sense of shame in the light.”

Likewise, in the same scene, Max dismisses the show trials the other ex-SS officers use to root out eyewitnesses as “a game for freaks” – a smart example of putting front and centre the sort of phrase a critic might use to diminish Cavani’s achievement.

There was little the director could do to guard her picture against the onslaught from some critics and censors. Cavani said: “Italy the movie was confiscated three times. It was forbidden to underage audiences. I had to go to the Board Of Censors, who knows why? Even back then it wasn’t clear. The director of the board told me, ‘Well, we won’t allow it to be shown because the woman is making love while on top of the guy.’ That, I had to say, almost made me faint. I was totally taken aback. I told him, ‘Sir, this kind of thing actually does happen, you know.'”

The Night Porter‘s rehabilitation really only began the following decade, when the picture was discovered by the art rockers Japan, who styled the cover art for their LP Gentlemen Take Polaroids after Cavani’s movie and openly referenced the film and the central character’s plight in the single Nightporter. The movie also echoes throughout the music video for Ultravox’s Visions In Blue and thus in Lufthansa Terminal’s Nice Video, Shame About The Song, the latter an inspired send-up courtesy of the Not The Nine O’Clock News quartet.

The passing of time also came to The Night Porter‘s aid. In 1995, it was shown for the first time on British television in its uncut form as part of BBC Two’s Forbidden Weekend. In the years that followed, the film’s reputation would continue to be revised ever upwards, culminating in it being screened as part of the Venice Classics season at the 2018 Venice International Film Festival in 2018.

The years would also be kind to the public faces of The Night Porter. At one point contemplating retirement, having been exhausted by the film and the critical reaction to it, Bogarde continued to work with daring European directors like Alain Resnais (Providence) and Rainer Werner Fassbinder (Despair). Rampling, meanwhile, carved out a fascinating career embracing big American films (Angel Heart, Spy Game), award-winning British pictures (The Duchess, 45 Years) and confronting continental fare (Lars von Trier’s Melancholia, Paul Verhoeven’s Benedetta).

And Cavani? She didn’t just survive The Night Porter; she positively thrived on the response to it, going on to stoke further controversy with The Berlin Affair in 1986 – another story of SS sex and obsession, this time set in the build-up to the second world war – and Francesco in 1990, starring Mickey Rourke as the titular saint, the seven-figure fee for which the actor donated to Irish Republican causes.

Still making films in her 90s, Cavani has long been a big deal in her homeland. In the English-speaking world, meanwhile, she is known either for 2002’s Ripley’s Game, starring John Malkovich as Patricia Highsmith’s man without moral fibre, or for The Night Porter.

And when the voices lowered and the teeth ceased gnashing, the world eventually listened. And when it did, some of us at least came to understand what Bogarde meant when he said: “It’s easy for me to see [now the film is finished] but it is – paradoxically, as it doesn’t appear to be – what I always hoped it would be, which is a love story of the most incredible kind… As one American newspaper said, ‘Even if you’re sick and mad, you can still love’.”