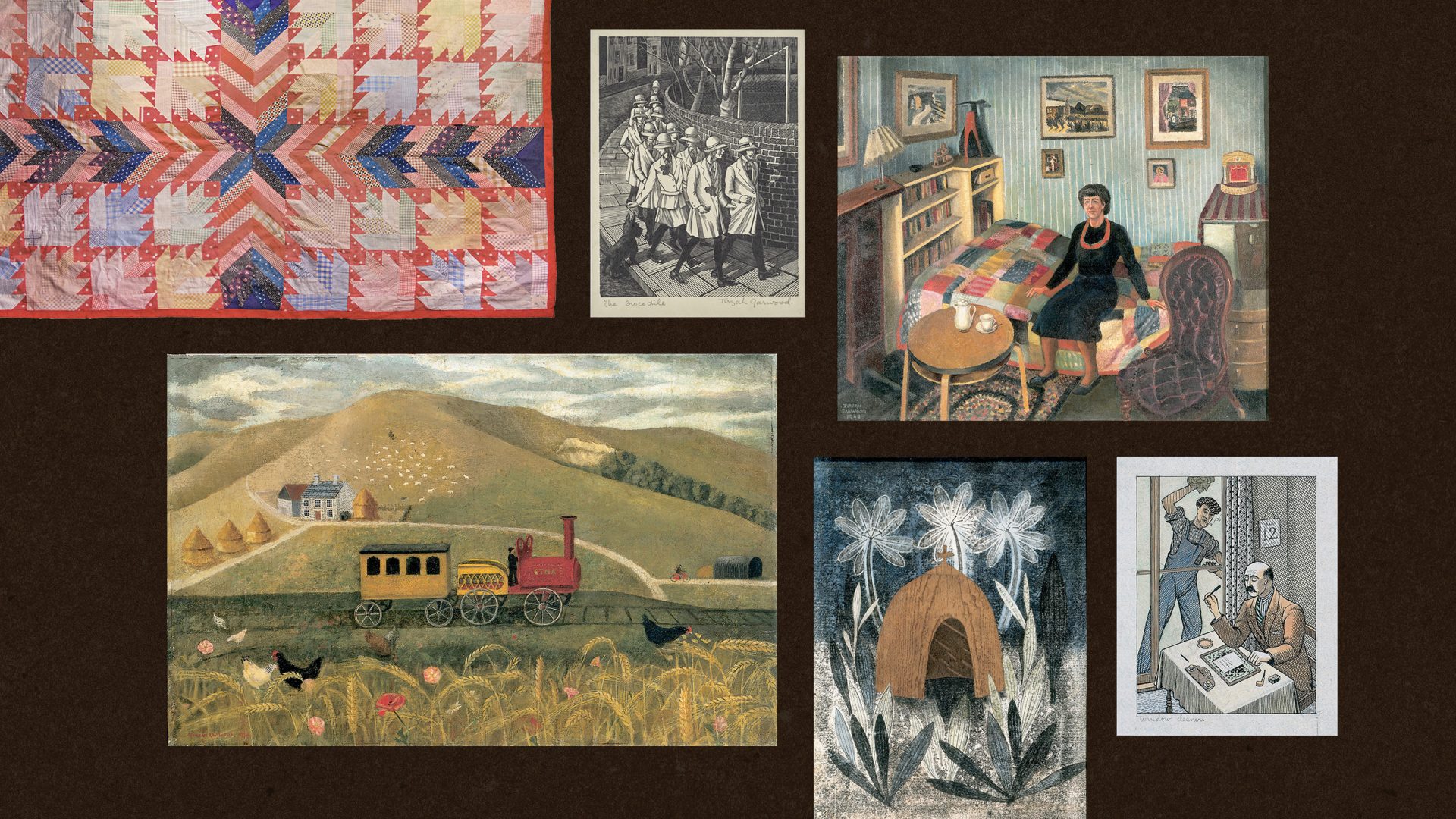

It might seem overly whimsical to pick out a scrapbook as a highlight of an exhibition, but there it is unobtrusively positioned among wood engravings, marbled paper patterns, quirky 3-D creations and mysterious oils.

It is jammed full of cuttings from magazines and newspapers compiled between 1947 and 1949, including cigarette cards of bi-planes over Eastbourne, adverts for haute couture in Paris, drawings of birds and beetles, any number of Father Christmases and clowns. Not to mention musical rats.

This fabulous gallimaufry is the creation of Tirzah Garwood, an artist whose talent was overshadowed by that of her husband, the watercolourist Eric Ravilious, but who at last comes out of the shadows at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in Tirzah Garwood, Beyond Ravilious.

Garwood (1908-51) met Eric, who was teaching at Eastbourne Art College, when she was 17 and he five years older. They married in 1930, by which time he had earned a reputation for his watercolours of the Sussex countryside with their lightness of touch and surprising perspectives. All charming, all pleasing to the eye.

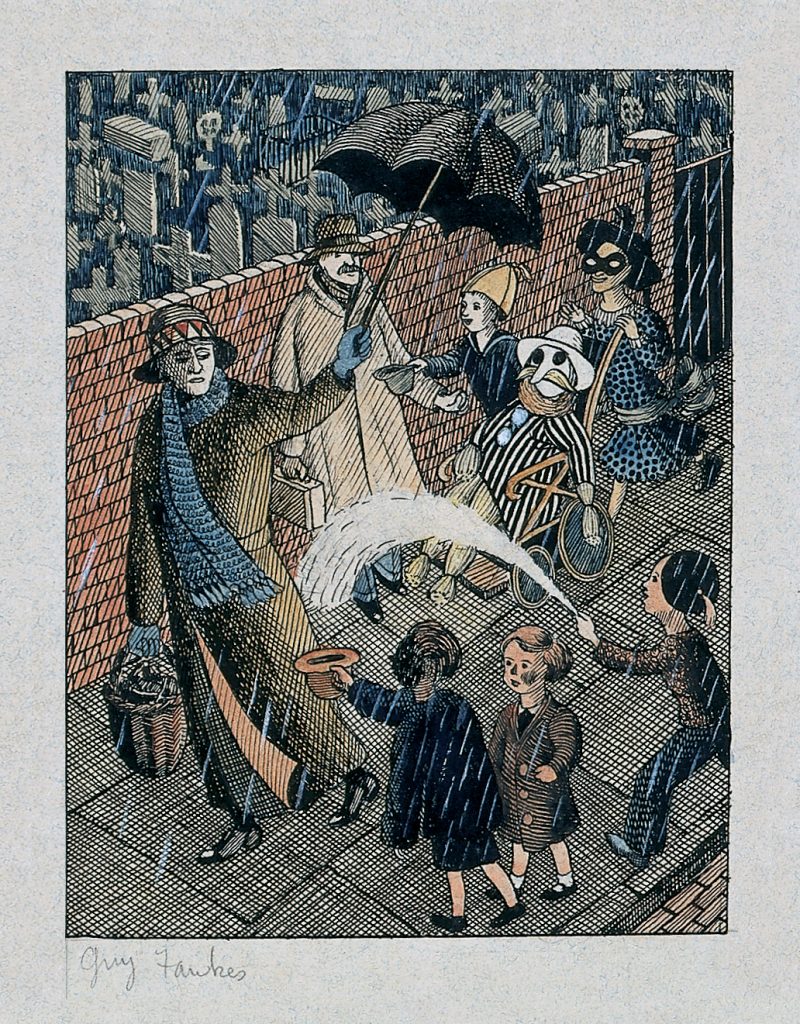

He encouraged her to concentrate on wood engravings which, as she gained confidence, became sharper both in style and content than her teacher’s. They capture the nuances of everyday life; The Grandmother – and her dog – fast asleep, book fallen from hands, The Train Journey, in which Garwood herself and two other female travellers are alert and looking while the men doze the journey away in their striped suits.

She captures the fashionable hurly-burly of Kensington High Street with its smartly dressed women and a shop window of posturing mannequins. She, identified only by TG on a case, hurries head-down through the crowd.

By the mid-30s she had begun to make a name for herself with marbled patterns on paper, shapes and colours that swirl like feathers or flowers, and with playful 3-D representations in cardboard, paper and wood of local schools, cottages and chapels.

But her life was to be thrown into turmoil. In 1942, Eric flew to Iceland in his role as a war artist, and died when the plane he was in crashed into the sea, never to be found. He was 39.

In her autobiography, she wrote about their last hours together with an unsentimental, yet moving, honesty. How she was too ill to make love, how he asked: “Shall I not go to Iceland?” and she replied: “No I shall be all right”.

When they kissed goodbye, “he said: ‘I love you Tirzah and I said: ‘I do you’, but at the moment I didn’t think as though I did. I accepted the fact that work was more important to him than me.”

A few days later she received the telegram informing her of his death and was struck with “spasms of dreadful sorrow”.

She was left suffering from cancer and with three children under seven to care for. It took more than a year before she began to emerge from her grief, moving to the Essex countryside, where she started painting in oil.

“I believe it might be my cup of tea,” she wrote. “I have always hankered after it because of being able to get things really dark.”

The first and the boldest painting of her new-found artistic freedom was The Cock, a proud, strutting creature, dominating a rural scene of rolling hills, a farm by a country lane and birds wheeling above the woods.

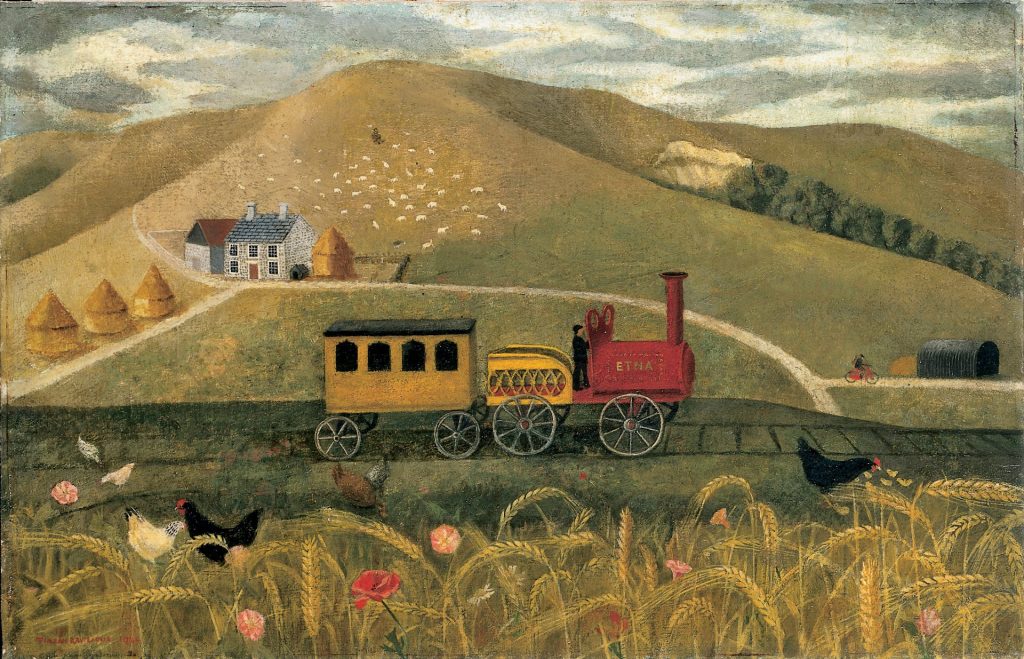

In the same year (1944) she conjured up the whimsical Horses and Trains using models of horses and a toy train by a tiny station, overshadowed by tall grass and poppies, and a few years later the playful but sinister The Old Soldier. Again, she used toys to depict a guardsman who has fallen to the ground, presumably shot by a soldier with a machine gun in a big black steamroller. To add to the oddity of it all a woman stands looking on from a balcony of a bright red and yellow house.

By 1950 as her death drew closer she was confined to bed for long periods but astonished her friends with her determination to keep painting.

If not “really dark” these last works, about 20 in all, are increasingly surreal, often using imagery that might have appealed to her children. They include Prehistoric Encounter, inspired by the time she and her daughter, Anne, found a frog in the garden. In a ghostly forest, bright with moonlight, a huge tortoise lumbers over the frog while a dragonfly hovers above.

In Suffragette’s House, matchstick dancers in tutus with flowers for heads dance around a stern black doll’s house, while in Weewak’s Kitten, a black cat looms threateningly over a toy castle surrounded by pretty pink flowers. But black pansies, symbols of reflection and contemplation, are reminders that the artist had only months to live.

One of the most moving, painted not long before she died in 1951 aged only 42, is Whither Will You Wander in which a mother goose leads her three young ones across the countryside head raised to confront whatever dangers may lie ahead for her, but more, for them.

The catalogue of an exhibition held a year after her death enthused about the dreamlike quality of the works, quite a contrast to the quotidien content of her early engravings.

Some have suggested that Garwood was liberated by the death of Ravilious to express herself more freely. There’s a sense of her independence in the way she re-worked some of his paintings as collages for the scrapbook, such as an unfinished scene of Newhaven harbour to which she added a seaplane cut out of a children’s book. She superimposed a toy drummer on to a painting of a woodland scene and set a game bird perched on a snowy branch in what looks like a shed with a random clock ticking away on high.

Maybe it is fanciful to see this appropriation of her late husband’s work as a feminist gesture, just as likely it speaks to “a housewife’s necessary economy of time and labour”. As her granddaughter, Ella Ravilious, writes: “Ultimately the scrapbook demonstrates the vigour with which Tirzah made art throughout her life.”

Tirzah Garwood, Beyond Ravilious is at Dulwich Picture Gallery until May 26