As a girl, Jawa El Khash visited the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra, the glorious desert trading post enriched over the centuries with Greek and Roman temples, theatres and grand colonnades which stalk across the dusty plain. “It’s something you don’t forget,” she recalls. “My sense of magic and surrealism was so magnified that just touching the stones I could feel their soul and the people who have lived there.”

The emotion she still feels about that long-distance visit is more than matched by the joy at the downfall of the Assad regime and the return of hope to the country she left in 2009 for Canada. As the 28-year-old explained in a call from Toronto: “By living here I have had the opportunity to develop my skills and ignite my imagination where it can roam free and build whatever it likes but now I feel there is optimism in the air at home and I am hopeful about the future.”

She has used that imagination using 3D models and film to “recreate” the city, much of which was reduced to rubble by Islamic State barbarians, as her entry for the latest edition of the Jameel Prize, Moving Images. The show is at London’s V&A until March 16 before heading to Bradford as part of the city’s year of culture.

artist Jawa El

Khashʼs The Upper

Side of the Sky. Photo: V&A Museum

from Ramin

Rokni Hesamʼs If

I had two paths,

I would choose

a third (2020)

which documents

the toppling of

political statues

in the Middle East

– from the 1953

military coup in

Iran to the start

of the Iraq war

in 2003. Photo: V&A Museum

Alfrajiʼs A Thread of

Light Between My

Motherʼs Fingers

and Heaven. Photo: V&A Museum

The abiding sensibility among the seven finalists is that of longing and loss, a cleaving to history and tradition, which is hardly surprising given that most of them have fled the turmoil and repression of their homelands for countries where they can express themselves freely.

Khandakar Ohida, one who does live and work in her home country of India, took the £25,000 prize with her film Dream Your Museum (2022), an endearing installation about her uncle’s collection of memorabilia which had lain hidden in trunks for 50 years.

Khash’s entry, The Upper Side of the Sky, could hardly be more different. Her virtual reality evocation of Palmyra is rendered in haunting shades of blue which beguile the viewers as they use a console to “walk” through courtyards and towering arches.

But, inspired by her grandfather, an agriculturalist of renown, she has softened the outlines of her virtual city which she once described as having the “harshness of modernism and brutalist architecture” by decorating the stones with flowers, trees and shrubs. Butterflies take wing, seeds are ready to ripen.

“During the process of creating it, I was thinking about the ancient historical context of the monuments at the time they were being lived in, what each building was being used for. Simultaneously I was creating a record for future generations to be able to revisit Palmyra, even though it had been completely destroyed, through the sense of optimism and surrealism.”

If Khash deploys sophisticated techniques to express her feelings, Sadik Kwaish Alfraji, an Iraqi living in the Netherlands, expresses his with animated charcoal drawings. Simpler but just as heartfelt.

He conjures memories of growing up in Baghdad with A Short Story in the Eyes of Hope (2023), an animated love story to his father whose life was one of poverty and struggle. A commentary is scrawled alongside the increasingly careworn face of his father and superimposed on the outlines of a map of the Baghdad streets which he would tramp in search of work.

Traditional burial prayers accompany the words which begin: “Born in the south in the land of water in the city of reeds he played with buffalo and listened to love songs” and ends with the painfully succinct: “He was born, he worked and he died.”

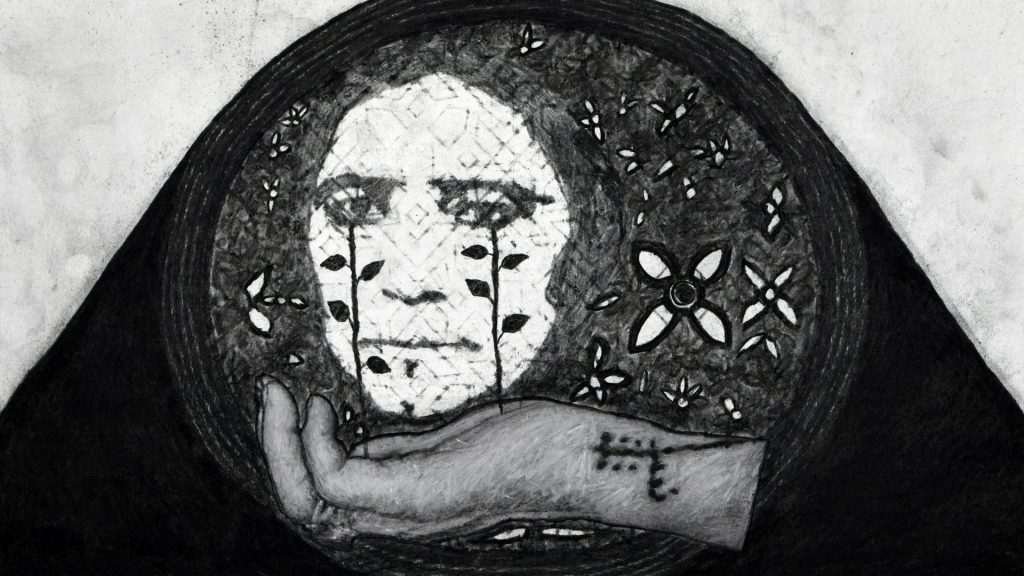

His other contribution, A Thread of Light Between My Mother’s Fingers and Heaven (2023), is a more complex work with imagery springing from his mother’s open palm. Gardens bloom with trees and flowers, which turn into eyes that slip out of sight to be replaced by the mythological creature Buraq, which carried the Prophet to the heavens and, incongruously, a copy of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper.

“I grew up with it hanging on a wall at home,” explains Alfraji. “It was always in my life. It makes me happy to see it, the pure beauty of it when we ate. It reminds me of the food mother gave us.

“But it’s not just nostalgia. By dealing with my own experience and memory I believe I can express a kind of a global experience. People will not necessarily know why the Last Supper is included but I invite them to dig into their own memories, their own emotions and daily lives and find something relate to.”

Alfraji admits that after two decades of living in the Netherlands, returning to Iraq only twice because his mother was dying, he is still uncertain where he really belongs.

This insecurity is not a problem affecting the high-profile trio of Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian, Iranian artists who quit the restrictions of Tehran for the freedoms of Dubai in 2009.

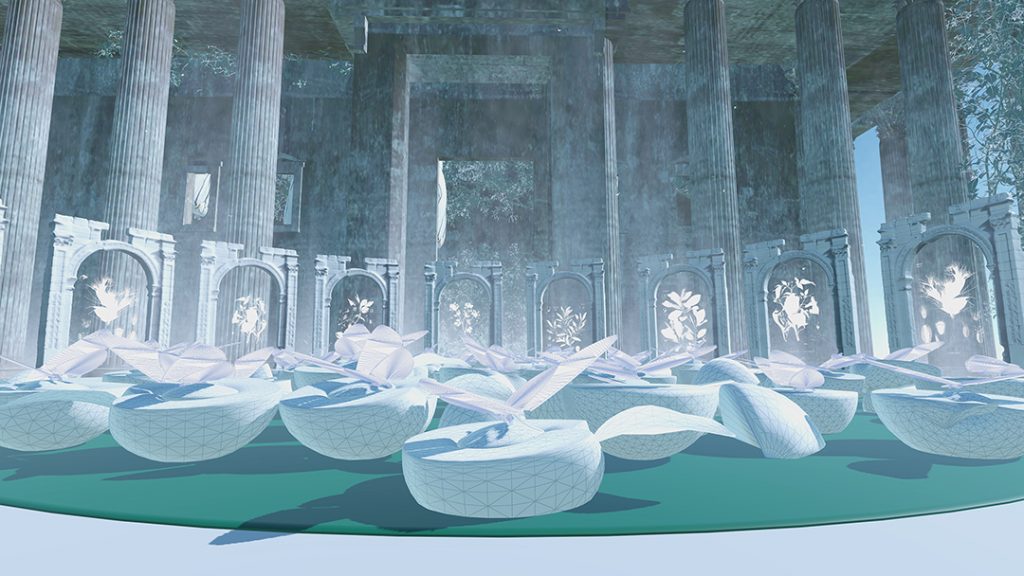

Their entry for the prize is the most flamboyant of them all, a video-cum-painting, If I had two paths, I would choose a third (2020), which dramatises the role of iconoclasm by setting it against key moments in Middle Eastern history from the 1953 coup d’etat in Iran to the start of the Iraq war of 2003 – all the more timely given the toppling of the statues of the Assad family.

Using their process of fluid painting, they took news footage of these events, printed out 3,000 individual pieces of paper on which they superimposed painted interpretation and transformed the composition into video.

They took inspiration from the Aja’ib al-Makhluqat (The Wonders of Creation), a 13th-century text on cosmography and summoned up the spirit of the djinn, the spectre from Arabic mythology which is unseen by humans and able to assume any form.

This mix of fact and fantasy finds expression in riotous street scenes peopled by monstrous creations; men with horns, gaping mouths and serpentine heads. A many-breasted female stands on top of a tank surrounded by men, heads painted in red rectangles, a man looms out of the crowd, his face painted in yellow and black stripes like a parrot. The statue of Saddam Hussein is wrenched ignominiously from the ground, his head a blob of red.

For all the embrace of the region’s myths and traditions, the trio have no desire to return to Iran. Not for these self-styled “people of the desert” the longing that characterises the works of Alfaji and Khash.

“We never tried to become nostalgic about the past or what happened,” they say. “We try to look at what is happening in the world now. You could even live in your own country and still be in exile.”

While they remain in their creative oasis, Jawa El Khash yearns to return to her homeland. “I am hopeful for a future with serious culture, serious museums, galleries, artists and thinkers living without fear.

“I’m looking forward to being a part of that generation that helps rebuild Syria into the country that we’ve always wanted it to be and to be able to freely grow as artists and as thinkers.”

Moving Images is at the Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington, London until March 16

Richard Holledge writes about the visual arts for the Wall Street Journal, Gulf News, Financial Times and the New European