When in 1905 a ragtag bunch of artists took over room VII of the annual Salon d’Automne, in Paris, the critics piled in. The “random gaudy colours”, and “frenzied brushes” were ridiculed mercilessly, and it wasn’t long before the room was nicknamed “La Cage aux Fauves” – the cage of wild beasts.

Today, the shock value of the Fauves’ vivid colours and highly expressive brushwork has waned, but the unalloyed machismo of the first avant-garde movement of the 20th century, expressed so forcefully in faceless, submissive female nudes, remains as unsettling as ever.

Records of the first Fauves exhibitions describe an all-male affair, with Matisse heading a roster of now-celebrated names including André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Kees van Dongen and Georges Braque, an artist best remembered for his role in the development of Cubism.

Kunstmuseum Basel’s current exhibition, Matisse, Derain, and Their Friends: The Paris Avantgarde 1904-1908, sounds as if it’s promising more of the same, but despite the title it pushes against old habits to trace the network of women who played significant if little-acknowledged roles in this short lived, but pivotal movement. Some were painters, and many were models, whose precarious lives, often as prostitutes, have previously rendered them more or less invisible. Others, like the dealer Berthe Weill, held positions of some power, and were instrumental in the trajectory of careers that have tended to be understood in terms of entirely male transactions.

It’s hardly surprising that, until now, the extent of female agency has been largely ignored in an art movement with a name that, as the museum’s director, Josef Helfenstein, points out, is laden with “virile connotations”. By 1910, the movement had dissipated as Cubism took hold, but in the press, the uproar surrounding that first Fauves outing seems hardly to have abated. The American wag Gelett Burgess regaled readers back home with tales of painterly abandon in his feature The Wild Men of Paris, a tag that delivers a noseful of primal masculinity to mingle with the musky reek of the animal kingdom.

“There were no limits to the audacity and the ugliness of the canvases,” he wrote in Architectural Record magazine. “What did it all mean? The drawing was crude past all belief; the color was as atrocious as the subject… Was nothing sacred, not even beauty?” And then there were the nudes, and plenty of them, “like flayed Martians, like pathological charts – hideous old women, patched with gruesome hues”.

In fact, women were involved right from the start, and the exhibition features three paintings by Émilie Charmy, who exhibited in that very first Fauves exhibition in 1905. The inclusion here of her astonishing self-portrait from 1906 both confounds and contradicts the “cult of the penis” that Carol Duncan describes in her 1973 essay, Virility and Domination in Early Twentieth-Century Vanguard Painting. In this germinal piece of feminist art history, Duncan argues that more than in any other period, the decade before the first world war saw artists “forcefully assert the virile, vigorous and uninhibited sexual appetite of the artist”.

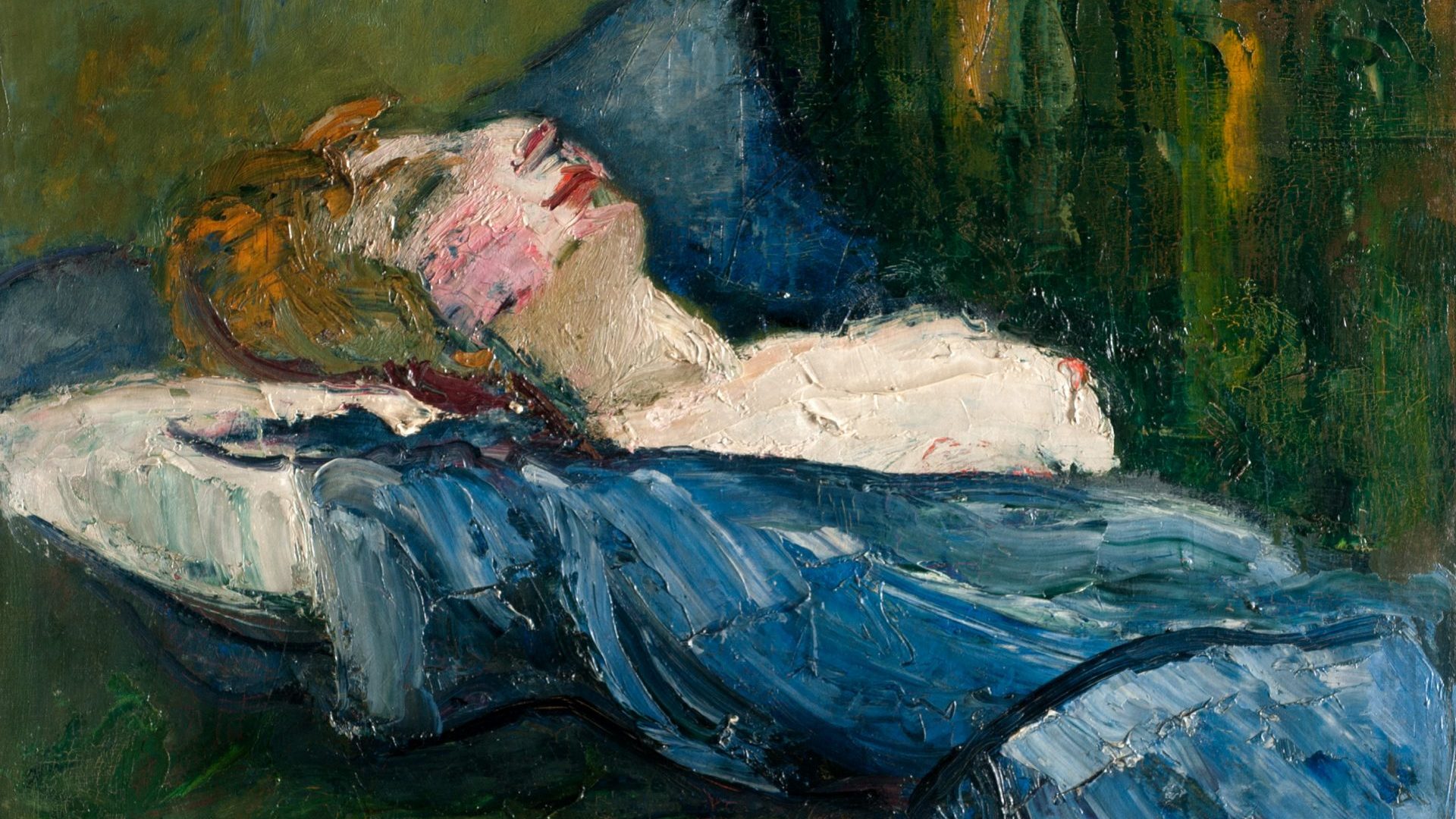

At first, Charmy’s self-portrait seems typical of the aggressive objectification of women. Her pose is open, her breast is exposed, and her flushed face, with eyes apparently closed, is simultaneously blatantly post-coital, and obscured as if erased.

But seen in context, the dark slits for eyes, the pink cheeks and the brilliant red of lips and nipple clearly refer back to another reclining woman, painted by Maurice de Vlaminck a year earlier. Vlaminck’s Nu couché is clownishly grotesque, with brilliant, unmixed colours daubed across her unnaturally white, masklike face. Her hand touches her breast, pushing it towards us, and her nipples are artificially red. We don’t know whether or not she is a sex worker, though the model who posed for the picture probably was: in this painting all we are asked to see is a submissive and sexually available female.

By comparison, Charmy’s self-portrait is a bold act of defiance. As both creator and subject, viewer and viewed, Charmy seizes power to herself, her indifference to our presence or gaze an assertion of female sexual autonomy. At a time when women were harshly judged for acts of supposed immodesty, it is a radical act of resistance.

Though French women were among the last in Europe to be permitted the vote, the boundaries of female existence were beginning to shift. In 1894, the painter Suzanne Valadon became the first woman to be elected to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and in 1897, women were finally allowed access to the École des Beaux-Arts, the country’s foremost art school, though they were taught separately and denied access to painting and life classes.

While the provision of state art education for women was well behind much of the rest of Europe, it had for some decades been the best place for women to access private tuition. Women from across Europe and America came to Paris in such numbers that in 1893 the American Girls’ Club in Paris was opened, providing cheap lodgings for students at private academies such as the Académie Julian. Recalling his own experiences of the Académie Julian in the 1870s, the Irish writer George Moore noted that in addition to 18-20 men, “there were also some eight or nine young English girls. We sat around and drew from the model.”

Marie Laurencin, represented here by four paintings, was a student at one of these private institutions, the Académie Humbert, while Charmy got her training in a painter’s atelier. The Swiss painter Alice Bailly attended the École des Mademoiselles in Geneva.

In contrast to the rather piecemeal education received by female painters, for their male peers the private academies generally served as preparation for the École des Beaux-Arts, which is where the core group of Fauves met in the 1890s, under the tutelage of the celebrated Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau. Such was the collaborative energy of this group that they continued to work together after their studies had finished, and the fruits of this period are powerfully evoked in the exhibition, and captured vividly in Albert Marquet’s 1905 painting Matisse dans L’Atelier de Manguin, which shows the improbably well-dressed Matisse hard at work at his easel.

The influence of Cézanne and of pointillism, distinctive for the application of dots or dashes of paint, combined with the colouristic and highly expressive landscapes of Van Gogh and Gauguin – themselves heavily inspired by Japanese prints – coalesced into a broadly coherent style in the summer of 1905. Matisse and Derain stayed at Collioure in the south of France, producing a series of paintings characterised by bold, vibrant colours, and a loose application of paint that was simultaneously shockingly unnaturalistic and evocative of movement and shifting light.

The chromatic distortions of Matisse’s La Plage Rouge, 1905, or Derain’s Bateaux dans le Port de Collioure, 1905, mark a moment of shared enterprise that a few months later would cause “the Salon scandal of 1905”. It was at this auspicious event that Charmy first came into contact with Matisse and the others, but it was largely due to another woman encountered here, Berthe Weill, that they were, if briefly, identified as a distinct group.

Following an apprenticeship to the antique dealer Salvator Mayer, Berthe Weill established her own gallery in Montmartre in December 1901. From the outset, she was a keen supporter of young artists, and her phrase “Place aux jeunes!” (Space for the young) served her well, along with an immensely well-developed understanding of the emerging art scene. As well as her early recognition of Matisse and his circle, she is distinguished as the first Paris dealer to sell work by Picasso.

In her first year of business, Weill included Matisse and Marquet in group shows, and by the time of the 1905 Salon d’Automne many of the Fauves, including Kees van Dongen and Charles Camoin had already appeared on her walls. For Charmy, the Salon d’Automne was a crucial opportunity, and though she doesn’t seem to have exhibited at Weill’s gallery until several years later, it was from that point onwards that Weill became her friend and supporter.

By the time Charmy painted Weill’s portrait in 1910, the two women were close friends, and in fact Weill continued her relationships with many of the Fauves well into the 1920s and 30s. She supported a number of female artists during her career, including Valadon and Laurencin.

Though principally an insult, describing an apparent ignorance of western art’s rules and traditions, the curator Arthur Fink points out that the term resonated with the fashion for non-western, so-called Primitive art at the turn of the 20th century.

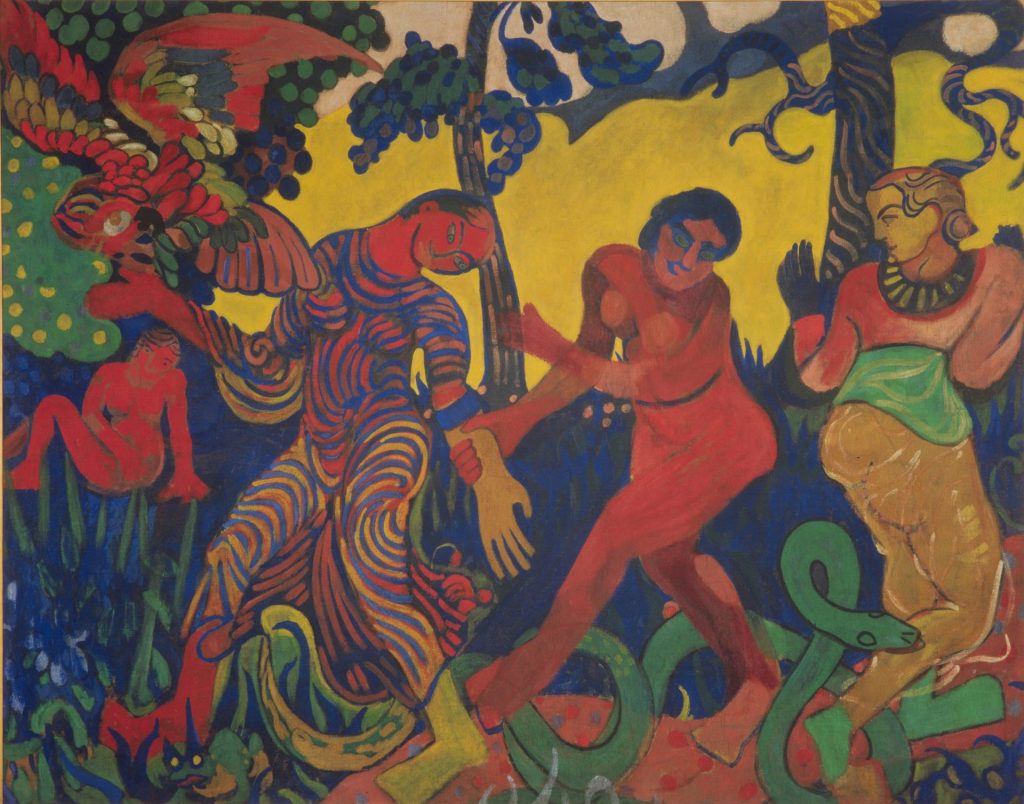

The interest in African masks, most famously expressed in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, may have begun with the Fauves, and both Matisse and Derain produced sculptures that emulated the stylised, simplified forms associated with African sculptures. Exotic plants, animals and landscapes were part of this same colonial-era fantasy, and in Derain’s La Danse, 1906, a scene of primal abandon harks back to some blissful, Edenic state.

There’s no getting away from the fact that the promise of sexually available women was a big part of this fantasy, which was to an extent lived out by artists for whom sexual adventuring was part and parcel of bohemian life. Camoin and Marquet spent a great deal of time in brothels, where they procured models as well as sex; by contrast, Charmy (who incidentally was involved with Camoin for a time) engaged sex workers as models in her studio, producing paintings that, like her self-portrait, reclaim female bodies from the male gaze.

If Charmy was able to command respect, at least partly through force of character, Laurencin had a different experience and was marginalised by male peers, who nicknamed her “la fauvette” and “the hind among the Fauves”. In her exquisite painting Diane à la Chasse, 1908, she invests the female nude with power, takes ownership of her nickname, and subverts the Primitivist trend in a stylised depiction of the goddess Diana that recalls medieval miniatures and manuscript illuminations. The goddess of the hunt is Laurencin’s alter ego, shown here sitting on the back of a deer. No longer “la fauvette”, Laurencin is an image of queenly authority.

Another woman often depicted in Fauve paintings is Amélie Matisse-Parayre, whose portrait in a hat by her husband, Henri, attracted special hilarity in 1905. In fact, Fink points out that her famous hats are rather more than a decorative flourish, since her millinery business brought some respite from financial distress, allowing Henri Matisse to dedicate himself to painting.

Her wider importance to the Fauves is established in several portraits by artists of that circle, including a 1904 portrait by Camoin, which shows her working on a tapestry, an art form that appealed to the Fauves because of its perceived distance from Fine Art. Noteworthy too is her kimono, which reflects not just the fashion for all things Japanese but the prioritising of comfort and physical freedom, which was so important to the burgeoning women’s suffrage movement.

By returning certain female figures into the narrative of this key moment in 20th-century painting, this exhibition adds depth and texture to a rather one-dimensional story. It includes research on the white slave trade that supplied Europe’s brothels, and a study of police records has allowed individual women to be identified, and their relationships with artists to be more clearly understood – if principally to confirm that, despite radical claims, the mainly male avant-garde was as rooted in the oppression of women and minorities as society at large. It shows that including women in art historical narratives is not a choice but essential if we are to find the nuance, and the points of resistance that ultimately force change.

Matisse, Derain and Friends: the Paris Avantgarde 1904-1908, Kunstmuseum Basel until January 21