If it weren’t for the low rail keeping the public at bay, you might think that the grand open space at the centre of the Bourse de Commerce in Paris had been turned into a makeshift camp. Or even that you had arrived mid-spring clean, the Rotunda a convenient collection point for sheets of glass, piles of old clothes and even some bales of hay.

The materials are certainly ordinary enough, and strewn as they seem to be across the interior of this venerable building, they make a pointed contrast to the values of commerce and capitalism that the Bourse de Commerce represents. None of this is accidental, of course, but instead a theatrical flourish by the French businessman François Pinault, for whom the building’s exalted architecture and history make an ideal backdrop for his collection of Arte Povera.

Inadequately translated as “poor art”, Arte Povera was a radical art movement born in the industrial centres of northern Italy in the late 1960s. Made using unconventional, lowly materials, it reacted against an increasingly complex, technological world, in which consumerism had produced an aesthetic of its own, typified by the sardonic cool of Pop Art.

Altalena per Bea, 1968. Photo: Rainer Iglar. Courtesy Fondazione Merz

Scarpette, 1975. Photo: R. Ghiazza. Courtesy Fondazione Merz

Pinault opened the Bourse de Commerce as a museum in 2021, its transformation from a defunct commodities exchange the fulfilment of a longstanding ambition to add a Paris venue to his Venice concerns. In the 16th century, it had been the site of Catherine de Medici’s palace, the only vestige of which is a freestanding column, built as an astronomical observation platform.

The present building began as a corn exchange in the 18th century, and was extensively remodelled in the late 19th century when it became a commodities exchange. The dome’s interior walls were painted with allegories celebrating France’s industrial and commercial might, its glass cupola, looking up to the great unknown, a macho metaphor for discovery and conquest.

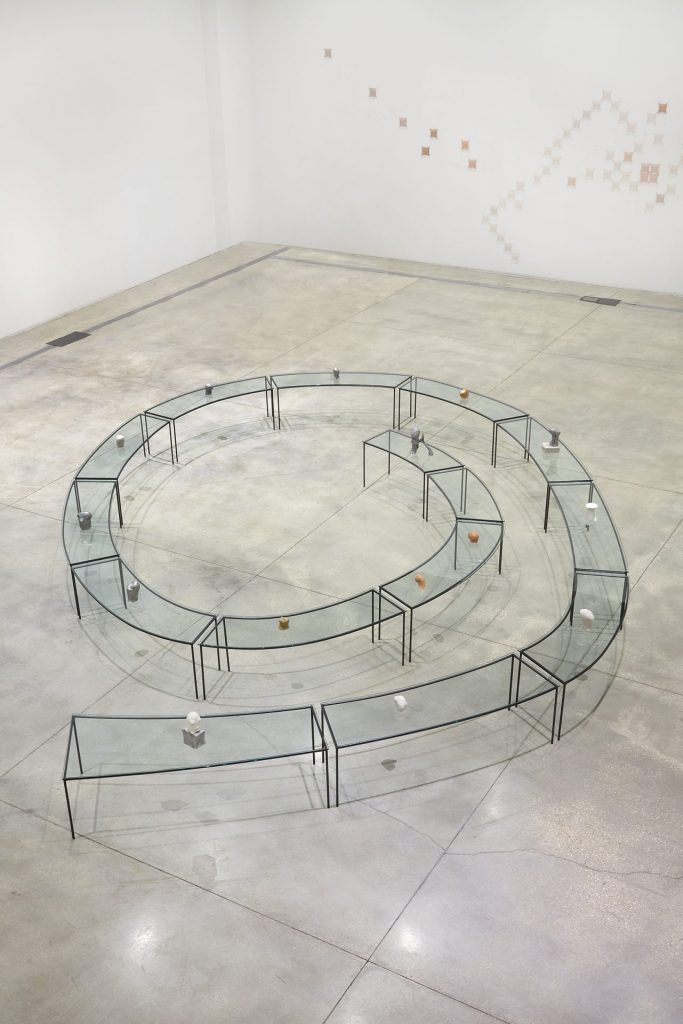

Against this backdrop, Pinault envisaged the 50 or so Arte Povera works from his own collection, noting, writes director Emma Lavigne, “the potential correspondences between the artworks and the spirit of this venue, like the semicircle of glass crowning the Rotunda and Mario Merz’s igloos that, according to the artist, are at once symbols of the world and little houses hesitating between void and solid, shelters ‘to confer some kind of social dimension to humanity’ and also, places in which to dream.”

Actually, the Bourse is far from an ideal place in which to dream – the vast round hall was far too well designed as a place of business and brass tacks to be truly satisfactory as an art gallery. Still, the exhibition’s curator, Arte Povera expert Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev has tried to make a virtue of its scale, its full extent a world in which visitors are free to wander and discover art in and out of the galleries, in stairwells, and other incidental spaces.

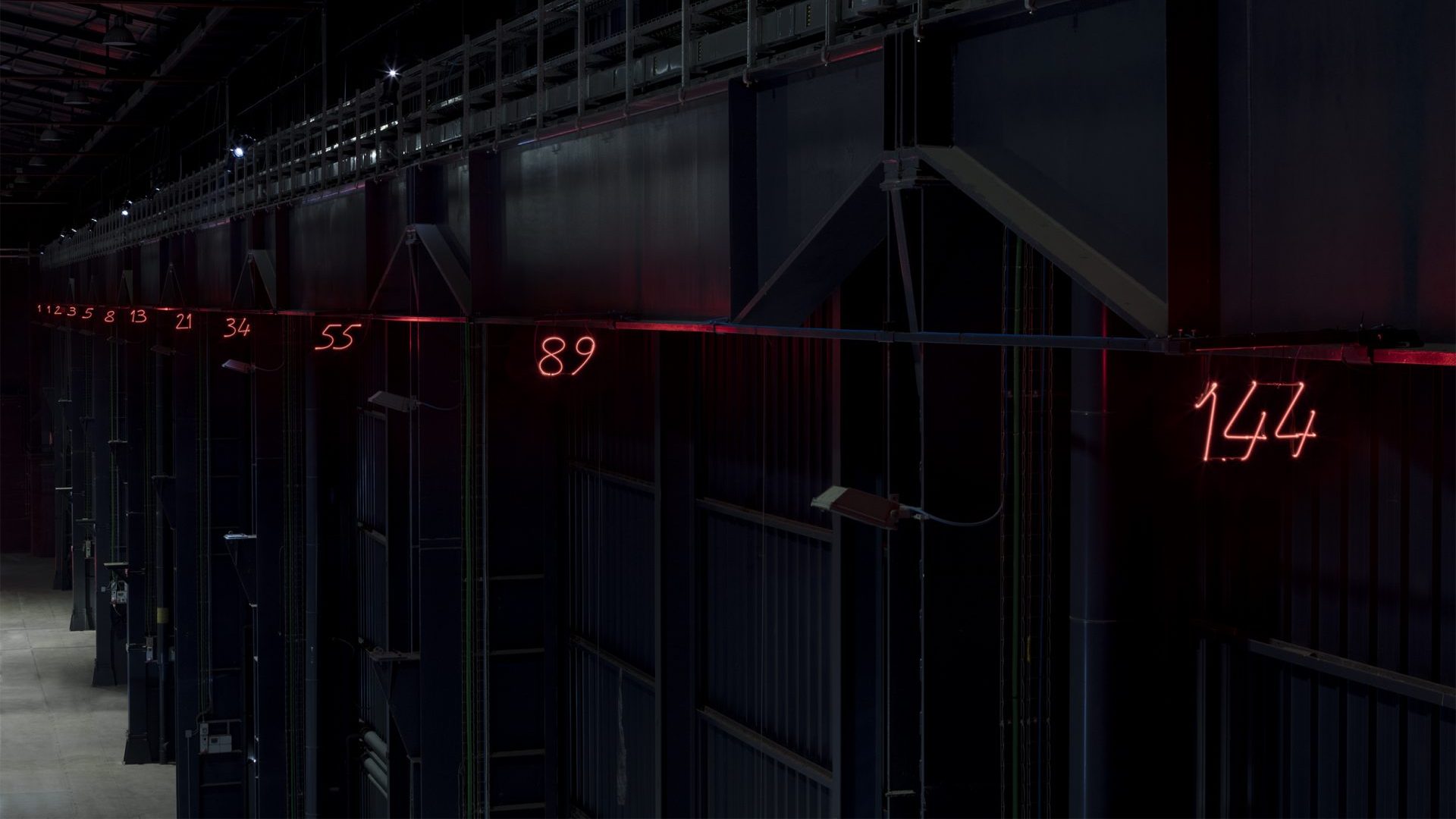

You’ll find Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Wardrobe, 1968-2024, a pile of clothes next to a full clothes rail, in a passageway by a window; Mario Merz’s series of red neon numbers Numeri di Fibonacci (Fibonacci Numbers), 1984-2004, is high up on the building’s exterior, unfettered by gallery walls.

An insistence on ordinary, everyday encounters with art, is one of Arte Povera’s defining principles, identified by the critic and curator Germano Celant, who in September 1967 organised the movement’s first exhibition, from which it took its name. “The commonplace has entered the sphere of art” he wrote in the catalogue. “Physical presence and behaviour have become art.”

Six artists appeared in Celant’s Arte Povera – Im Spazio, at La Bertesca gallery in Genoa: Alighiero Boetti (1940-1994), Luciano Fabro (1936-2007), Jannis Kounellis (1936-2017), Giulio Paolini (b.1940), Pino Pascali (1935-1968), and Emilio Prini (1943-2016). They are among the 13 key artists highlighted in the current exhibition, which features works from that original show, including Jannis Kounellis’s Senza titolo (Carboniera) (Untitled – Pile of Coal), 1967, in which coal brings to mind the Industrial Revolution, and carbon as a building block of life, and Emilio Prini’s Perimetro d’aria (Perimeter of Air), 1967.

All 13 artists are included in the opening display in the Rotunda, adding one woman, Marisa Merz (1926-2019) to Celant’s original group, plus her husband Mario Merz (1925-2003), Giovanni Anselmo (1934-2023), Pier Paolo Calzolari (b.1943), Giuseppe Penone (b.1947), Michelangelo Pistoletto (b.1933), and Gilberto Zorio (b.1944).

Its free and easy presentation is evocative of the early Arte Povera exhibitions, and what the curator calls the “horizontality” of Arte Povera (translation: pieces are displayed on the floor more than the walls) is emphasised in a free-flowing arrangement of works that reproduces the slightly chaotic displays at Deposito d’Arte Presente, in Turin, where, in the late 1960s artists were invited to turn up and exhibit their work as they wished.

Those northern Italian cities that nurtured Arte Povera are proud of the connection, and are home to major collections which have been essential to this exhibition of more than 250 works. The Museo e Real Bosco di Capidimonte in Naples has loaned works, as have three Turin-based institutions, the Fondazione Guido e Ettore De Fornaris, the Fondazione per l’Arte Moderna e Conemporanea CRT and the Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, where until last year, curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev was director.

The Fondazione Arte CRT is a private philanthropic organisation with its roots in banking, its goal “to enrich and enhance Turin and the wider Piedmont region’s art and cultural offering with a focus on modern and contemporary art.” Around 90% of its collection is publicly accessible via two Turin museums, the Castello di Rivoli and GAM, the Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, and 23 works are on loan to the exhibition.

Its president, Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo explains that the foundation is rooted in Arte Povera, its core collection established 20 years ago from the private collection of Margherita Stein, a Turin gallerist and early champion of Arte Povera who died in 2003. Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, herself a collector of note is passionate about the movement, which she says deserves a higher profile outside Italy, something she hopes the Paris exhibition will encourage.

She believes that Arte Povera has particular currency today, as artists attempt to negotiate rapidly advancing technology, and the climate catastrophe: “They have been able to anticipate so many things through their work and so for that are very inspirational”, she says, pointing particularly to the work of artists like Giuseppe Penone, whose focus on nature and natural materials is particularly prescient.

Individual galleries are dedicated to each of the core artists, and Penone’s is distinctive for its materials which include soil, plants, branches and sawdust. Acacia thorns are glued to a large canvas in a dense uneven cloud that has the appearance of a swarm, or murmuration, at the point of a shape-shift.

The thorns form a close up image of a closed eye in a human face, a small sheet of gold leaf resting at its corner to make us feel its extreme delicacy, the gold leaf like the eye precious but exquisitely vulnerable.

The power of nature as an active, and potentially destructive force is implied in this work from 2002, but in his works with trees, which have been a consistent motif ever since the beginning of his career, nature is harnessed as a tool. A series of photographs titled Alpi Marittime (Maritime Alps), 1968-89, documents various actions, including covering his body with spikes to imprint himself on a tree, and covering the top of a tree with a weighted cage, in an action titled When Growing, It Will Raise the Net.

In 1969 he began another tree-related series, in which he took a beam, and following its growth rings stripped back the layers of wood, undoing time and the human action that had produced the beam, to recover the form of the tree.

As with Penone, there is a beguiling, magical quality about the work of Marisa Merz who as Arte Povera’s only major female artist is less known than many of her peers, which makes the space dedicated to her here especially meaningful. In fact, her space overlaps with that of her husband Mario Merz, though since they often worked in dialogue and collaboration with one another this is not unreasonable, as indicated by Mario Merz’s Igloo (di Marisa), (Marisa’s Igloo), 1972, constructed from soft sewn blocks made for the purpose by Marisa.

Marisa Merz’s environment was the home, but as for Penone, the passage of time features prominently. Just as he was constrained by the growth of a tree, Merz’s Living Sculptures, which she built up from strips of aluminium foil, are accumulations of material that are themselves the evidence of the time invested in their construction.

They were shaped too by the daily domestic routine, and the sculptures, which often grew to be very large indeed, were suspended from the ceiling each evening when she cleared the table to make space for her family’s evening meal.

Her Altalena per Bea (Swing for Bea), 1968, is still more explicit in its framing of female, domestic experience. Set on a slope, the sharp points of its triangular “seat” are alarmingly lacking in maternal care, its impractical, indoor design in claustrophobic opposition to the wholesome freedom associated with a child’s swing.

Her own words about it are similarly ambiguous, and capture the mixture of contradictory, “unacceptable” feelings that mothers can sometimes experience: “I stopped. I sat down in this chair. Two years sitting down. I would get up only to take care of Bea. I wasn’t making any art, but I kept on for her sake. She was fantastic. I learned so much from her (and she, nothing from me).”

Her references points do extend beyond the home, however, and in an awkward, if informative display, a 15th century Madonna and Child by the Sienese painter Sano di Pietro in placed in conversation with the clay heads (Testine), 2002, of her later career. Similar “historical references” appear at other points in the exhibition and are intended to give a sense of Arte Povera’s indebtedness to the past, in contrast to avant-garde movements that so often position themselves in opposition to what has gone before.

Likewise, the inclusion of works by contemporary artists such as Theaster Gates and William Kentridge suggests that Arte Povera is not so much a past event, but a continuing strand of thought.

Slipping easily across time is the Greek-born artist Jannis Kounellis, for whom fire, iron, coal, rocks, coffee grounds, beans and even live animals make crudely elemental materials that seem to have come straight out of the earth, with which he creates symbolic and often highly theatrical productions. A feeling of magic, or alchemy often adds to the sense of a man working out of time, and in one extraordinary and celebrated work he brought 12 horses into a Rome gallery, briefly returning a corner of the city to nature.

Kazimir Malevich’s 1917 painting, Dissolution of the Plane, has been selected as Kounellis’s “historical reference”, a choice that quite persuasively makes the case for Arte Povera as an important moment in 20th century art, and Kounellis as its foremost practitioner.

Though Malevich’s rejection of representation seems remote from the “thingness” of Arte Povera, it is a direct antecedent of Kounellis’s own rejection of representation in favour of real objects – horses, piles of charcoal, flames – which in their instance on the real form a chain that extends back to those early cave paintings, when artists left impressions of their hands on walls.

Arte Povera is at the Bourse de Commerce, Pinault Collection, Paris until January 20, 2025