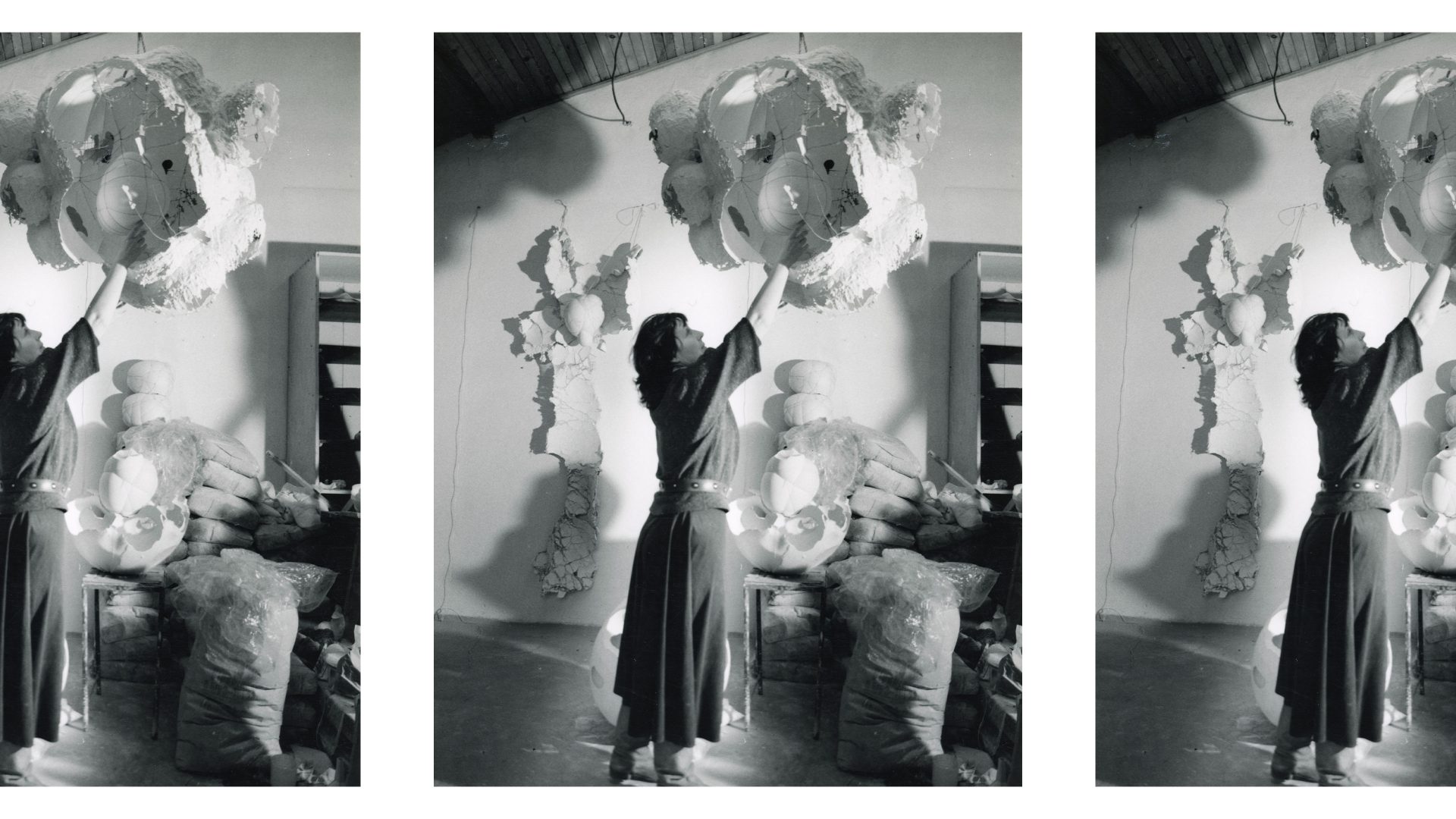

Playing with an inflatable ball with her daughter one day, the Slovakian sculptor Maria Bartuszová (1936-1996) had a eureka moment. What if she filled party balloons with poured plaster? Sometimes gravity did its work as the plaster set, as in the early sculpture Untitled (Drop), 1963-4, whose pendulous form is held for ever in the moment just before it is dispersed by

critical mass. Sometimes she used her hands to shape the still pliable form,

often working the filled balloons under water, where the plaster’s natural

buoyancy allowed her to manipulate and turn the sculpture with ease.

“Gravistimulational casting”, as she called it, became Bartuszová’s go-to method during the 1960s and 70s, and she used balloons, condoms, and even

weather balloons to create often highly complex plaster forms that recall the

dynamic growth of the natural world, from the formation of raindrops to bursting buds and unfurling leaves.

Bartuszová had only two solo exhibitions in her lifetime and though plaster was always her principal material, these focused on her works in bronze and aluminium. She was little known internationally until 2007, when she was included in the German modern art exhibition Documenta. In 2010, she was included in a survey of central and eastern European art at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, and this year in the main exhibition at the Venice Biennale.

Showing alongside Cecilia Vicuña’s Turbine Hall installation at Tate Modern, and exhibitions dedicated to Magdalena Abakanowicz and Barbara Hepworth opening later in November, Maria Bartuszová at Tate Modern is one of a group of Tate exhibitions exploring the impact and legacy of female sculptors in the 20th century. It charts Bartuszová’s career from the 1960s and 70s, following her changing techniques and vocabulary into the 80s, and exploring the entire breadth of her career from small, handheld works to large public commissions.

Born in Prague, in what was then Czechoslovakia, Bartuszová went to art school in the early 1950s before taking a job at a ceramic works. She went on to study ceramics at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, where she completed her diploma in 1961. She married fellow sculptor Juraj Bartusz the same year, and gave birth to her first child, Anna.

As part of the eastern bloc of countries under the yoke of the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia was subject to a totalitarian regime from 1948, and access to the West was strictly limited. After the death of Stalin in 1953, curbs on personal freedoms and freedom of expression were lifted somewhat, with

increased opportunities for artists to show their work publicly and to see exhibitions of western artists.

The influence of artists including Henry Moore are evident in the abstract, yet recognisably natural forms of Bartuszová’s work, and in her increasing

interest in the dialogue between open and closed forms, empty internal space and surface, there are parallels with the work of Hepworth. Indeed, though Czechoslovakia endured Soviet occupation from 1968 onwards, between 1966 and 1971 exhibitions of Moore, Pablo Picasso, Yves Klein, Marcel Duchamp, Bridget Riley and the Gutai group all took place in Czechoslovakia.

In 1963, Bartuszová and her family moved to Košice, now in Slovakia and

then a rapidly developing industrial centre with plenty of cheap housing.

The construction boom provided lots of opportunities for work, since by law all new buildings had to include a newly commissioned work of art.

Having joined the artists’ union in 1964, Bartuszová was licensed to work as a professional artist, and through various public projects, including the sculpture for the crematorium in Košice, and on the front of the Lipa department store, Bartuszová provided a steady stream of income for the household.

With their characteristically organic forms, public projects such as the crematorium sculpture are a continuation of the ideas Bartuszová was working on in her private work on a smaller scale. But though she managed rather skilfully to sidestep the ideological demands of the regime, Bartuszová was undoubtedly under scrutiny from the authorities.

As Marie Klimešová of Charles University, Prague points out in the exhibition catalogue, for the five decades up until the so-called Velvet

Revolution in 1989, “Czechoslovakian artists lived in a country where every

artistic work was to some extent a political statement.”

Certainly, Bartuszová herself felt the strain of these conditions, and noted in

1968: “Influences (on creative work): feelings of anxiety in totalitarianism, and the cold war tensions. The ban on abstract art in totalitarianism increased its importance.”

According to the curator, Juliet Bingham, although Bartuszová managed to remain largely untroubled by the regime, pursuing her own ideas in public sculptures across three decades, her refusal to engage in propaganda or ideologically motivated art confined her to less prestigious commissions. That her work refers often and quite frankly to the messier aspects of female experience may also have kept her away from more prominent commissions.

“There’s a sort of intimacy to her work, which at the time maybe was sort of a reason why she was less recognised, that intimacy and expression of female experience, drawing on her own experiences as a mother and partner and caregiver and the body, I think that would have been less accepted then,” says Bingham.

It’s an overwhelmingly feminine visual language of ripeness and fertility, rooted in Bartuszová’s own experience of motherhood, which is transferred

holistically to the works. Shaped and visibly marked by her hands, they embody a nurturing touch amplified in projects such as her designs for children’s climbing frames.

She also created a series of “haptic” sculptures that came apart and could be

put back together rather like a puzzle. The art historian Gabriel Ladek photographed these “folders”, as the artist called them, being used in workshops that he organised for blind and partially sighted children in 1976 and 1983.

The tactile nature of her work extended beyond the nurturing touch to the sensual, and Bartuszová explored the erotic potential of swollen, bulbous forms, often conjoined and coupled: “Rounded organic shapes appear warm and, when touching, can create the feeling of a gentle caress – maybe even an erotic embrace.”

For the most part, Bartuszová worked in isolation, without the support or intellectual stimulus of a circle or artistic community. The single short period in 1969 when she associated with The Concretists’ Club yielded dramatic results that stand out from the rest of her work for their geometric and faintly industrial appearance.

The stringently abstract approach of the concretists, who eschewed any

reference to the observed world, was not sustainable for Bartuszová, but it

did hone her interest in meshing and interlocking forms, not just in the

“folders” of the 1970s, but also in large-scale sculptures such as Metamorphosis, Two-Part Sculpture installed outside the Košice Crematorium in 1982.

In the 1970s, her sculptures became more directly personal, while at the

same time retaining the sense of the universal and truth in nature that runs

like a thread through her career. Marks left in the plaster by her fingers make her presence and her absence equally, simultaneously felt.

Pressure, tension and confinement become new themes in these years, expressed often in composite forms made of contrasting materials. In

Untitled 1972-4, plaster is sandwiched between blocks of wood; in another

Untitled sculpture from 1973, an elastic band around plaster transforms

abstract inanimate forms into something decidedly corporeal, culminating in the much more explicit Rebound Torsos of 1984, which quite openly recall the sadistic photographs by the German artist Hans Bellmer, in which his bound lover Unica Zürn is made to represent a trussed joint of meat.

Despite evoking the objectified female body, Bartuszová’s bound forms lack the overtly sexual nature of Bellmer’s photographs, and instead seem to tackle something more spiritual. Just as she saw rounded forms as evocative of human warmth, she said of her bound forms: “The ropes, strings, and hoops that sometimes bind the rounded shapes could be symbolic of human

relationships or the constraints that limit the possibilities of living things –

the diseases and stresses that undermine what is alive and already restricted by its lifespan.”

As Bartuszová faced ill health, and the failure of her marriage in 1984, her work took a melancholy turn, the ripe forms of the 1960s replaced by broken, fragile and empty forms that, writes Bingham, “resemble abandoned cocoons, perforated ovals and empty shells, alongside fragile spatial environments.”

These she achieved through “pneumatic casting”, where she first inflated the balloon, and then poured a thin layer of plaster over it that once hardened, and the balloon removed, would leave a hollow shell. These were the basis for the Endless Eggs of the 1980s, compositions made up of hollow forms nested inside each other. The personal significance of these forms she captured in her own words: “In the quiet of depression / in the depression of the quiet / I am waiting hidden in the shell / of an egg to be born again.”

Despite the autobiographical element of her work, she seems always to have been looking out as much as in, not only in the steady stream of public commissions that she maintained throughout her career, but in her understanding of sculpture as a means to extend a sympathetic hand in a deeply isolated society.

Now, more than a quarter of a century after her death aged just 60, Bartuszová’s work offers a deeply compassionate view of art as an agent of solidarity and shared expression in the face of an oppressive and unyielding regime.

Maria Bartuszová, Tate Modern until April 16, 2023. Florence Hallett is a

freelance art writer and critic