How to capture the mayhem on the streets of Tehran? How can photographers reflect the iniquity of the Iranian regime without being seized by the Revolutionary Guards, imprisoned and tortured? The answer: by stealth.

Fariba Farshad, co-founder of Photo London, which is featuring the works of several Iranian photographers among an impressive international roster next month, is Iranian-born and the challenges facing the artists resonate profoundly with her. She says: “This situation today is more visceral and immediate than before, and although some of the most powerful comments coming out of Iran are photographic (think of the famous image of a girl standing on the roof of a car, facing an endless crowd of protesters, with her hands raised) many of Iran’s finest photographers are not making straightforward photojournalism.”

Speaking shortly after the regime had been damned by the United Nations for murder, torture and rape, she admits: “The true artistic responses to the current situation will take time to evolve and to find their way into the gallery and art fair system. Iranian artists working inside Iran will simply need to proceed with greater stealth.”

The admirably artful tactic is demonstrated by work that ranges from the factual to the surreal, from the self-referential to the abstract. Roya Khadjavi projects and Nemazee fine arts, who is representing an eclectic group at the show, elaborates: “The photographers get their message across by using metaphors and through symbolism, not by directly attacking the subject matter. They take photographs that say one thing but could mean another.”

It is a strategy that Tahmineh Monzavi, 35, has embraced with panache. As a young photographer, she resisted her teacher’s exhortation to stop taking “dark and unpleasant” photographs and to concentrate on nature or flowers. Instead, she set her lens on controversial subjects such as transgender people, homeless people, drug users and sex workers, subjects that did not endear her to the authorities. She was arrested and put in solitary confinement for a month.

So traumatic was the experience that she admits: “I lost my courage as a documentary photographer” and stopped work for two years.

Now, however, she has found a way to tell stories by using her photographs as metaphors.

In a Zoom call from Tehran she explained: “You cannot say anything directly, but there are many different ways to send messages that are like a poem, using the places, the faces. For me this is a way of explaining our lives.”

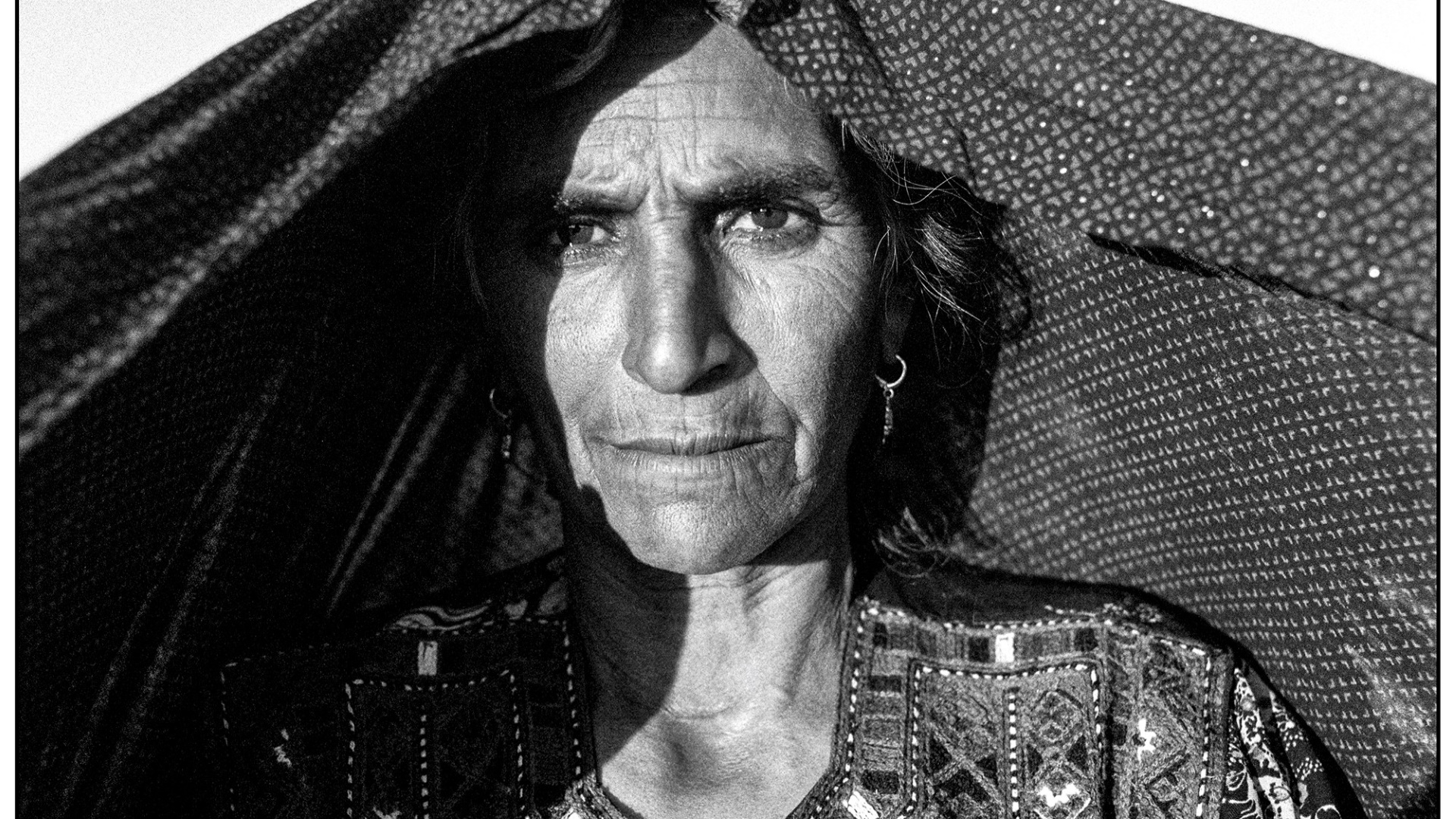

In 2018 she resolved to go to the Baluchistan region in the remote south-east of the country, where she lived among the Zangi women, whose slave ancestors had been brought into Iran as servants from east Africa 200 years ago.

Monzavi says: “Through my images, I have tried to capture how these women have remained isolated from the development of the modern state system, often victimised by the country’s Shiite majority for their Sunni beliefs, and how they have maintained their cultural practices.

“Their ancient nomadic way of life has been threatened by the building of a dam in Afghanistan that has cut off the water to Lake Hamoun on which they rely, not just for themselves but for their sheep and camels, which are dying from lack of water.”

The result is a distinctive essay in black and white, depicting the difficult world of the women; a quartet walking across the barren landscape balancing firewood on their heads, the lined, long-suffering faces of elderly people, a group brandishing knives while standing with branches in front of their faces because they do not want to be recognised.

These images are not overtly political, but they speak of the dispossessed and the despairing.

The defiant, too.

“I cannot say anything about the recent troubles,” says Monzavi, who refuses to join the growing diaspora of Iranian artists who have fled to the west. “In the streets, I saw many girls injured. It was heartbreaking that I couldn’t do anything, but even if I was to express my feelings abroad I would be punished when I got home.

“My family, my parents, my husband are here, my roots are here. I was in France for four months and I felt so isolated that I could not do anything.

I love to take my photos in Iran.”

The tug of home against the hope of finding freedom in a foreign country is exemplified by Babek Kazemi, who explores the history of his home province of Khuzestan, focusing on the impact of oil production on the region.

Each of the 50 photos in the set entitled Past Continuous Tense shows the same cloud, dark and threatening, hovering over the countryside. The symbolism of an oppressive state is obvious but the scenes below are more complex – a man on a chair looking quizzically at an empty chair with another man on his back on the ground, wheat blowing in the wind, a lonely woman standing in a field, a boy flying a kite.

The scenes are filled with melancholy and humour. They speak of a love and concern for his country. Nonetheless, Kazemi, 40, moved to London a year ago because, as Elisenda Faustino-Deu, owner of the gallery LS10 that shows his work, says: “The situation had become a nightmare.”

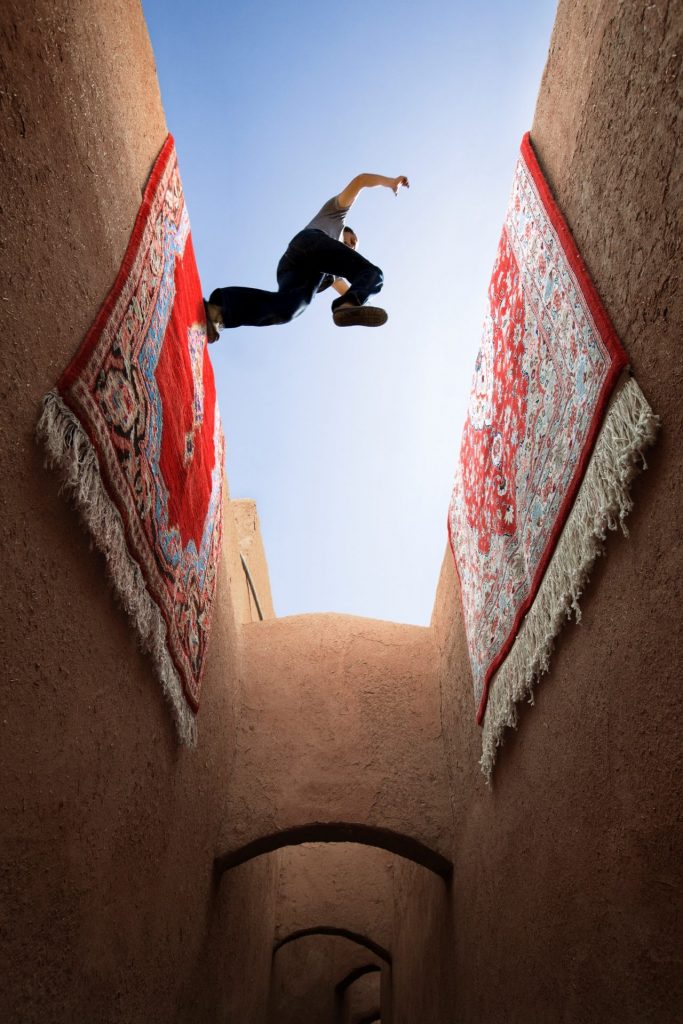

The contribution from Jalal Sepehr, another LS10 regular who is still living in Iran, could hardly be in greater contrast. His images in the series Water & Persian Rugs and Knots are a burst of joyous colour in which a traditional Persian rug is used in quirky situations. The rugs float and dance with men falling off them, jumping over them, racing past in a speedboat or emerging spluttering from the sea to walk to the shore on a long, bright (wet) runner.

On the face of it, it’s all fun and games, but every family in Iran has a rug and here it serves as a symbol of home, history and heart.

Inevitably, many photographers have moved away. Ali Tahayori fled to Australia to escape the homophobic climate of 1980s Iran. His contribution is a startling recreation of the library where he had his first sexual encounter with an older man. It is a disconcerting set with what is coyly referred to as bodily fluids spattered against the bleak scene of the seduction. Imagery that would horrify the Ayatollahs.

Dariush Nehdaran, 39, who has also moved away – to San Francisco – is another subversive, writing on his website: “Following the rules is an anathema. I’d like to delve into reality, discover and expose it, to create an individual and alternate interpretation.”

In The Life of Shadows, set in his home town of Isfahan, he does just that, playing with long, black shadows of walkers stretching across busy locations and lonely streets. They are taken from the side, from above and from implausible angles. Perspectives are skewed, reality turned on its head. It is delightfully discombobulating.

Reality was always faced head-on by Kaveh Kazemi (b. 1952) who has worked for publications such as Time, Newsweek and the New York Times covering many international conflicts, including the 1979 revolution against the Shah and the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-88. As a collection of his prints demonstrates, he helped to bring those tumultuous days into dramatic, often poignant, focus, not least with his Crying Soldier (1980), showing a member of the Revolutionary Guards weeping alongside his dead brother.

He is one of two photographers represented by the O Gallery in Tehran; the other is Mohammadreza Mirzaei – and there could hardly be a greater contrast.

Mirzaei, 37, has taken inspiration from his adopted home in the US, where he moved in 2012 for his latest work, an apparently random selection of images – an array of false nails, a sylvan waterfall, a reclining woman in a swimsuit, her face blotted out, and what looks like a sheet of cardboard thrown on a pavement.

“It demonstrates my encounters with different aspects of America, its landscape and its cities,” says Mirzaei, who is a PhD candidate in the history of art and architecture department at UC Santa Barbara, California. “But at the same time, it is related to the story of photography in which America and its photographers have played a significant role and informed my own practice in Iran. While my pictures might sometimes look like those examples from American street photography, they intend to problematise the documentary qualities of such pictures.

“This series does have a rationale behind them. How I line up the images, and how I work on the project is basically related to my experience as a foreigner.

“I think you cannot deny you belong to somewhere else and when you come to another country at my sort of age. You feel a void of memory, friends, and relationships. The meanings are different for me. At times, the new meanings are even meaningless to me.”

Even a gnomic claim like that has not spared him from criticism that his work lacked the hard edge of reality and was devoid of any political message.

But, he says: “I don’t think my work is not political. Artworks can be political in different ways. We are talking about art that is about freedom.”

Photo London is at Somerset House on the Strand, London, from May 11-14.