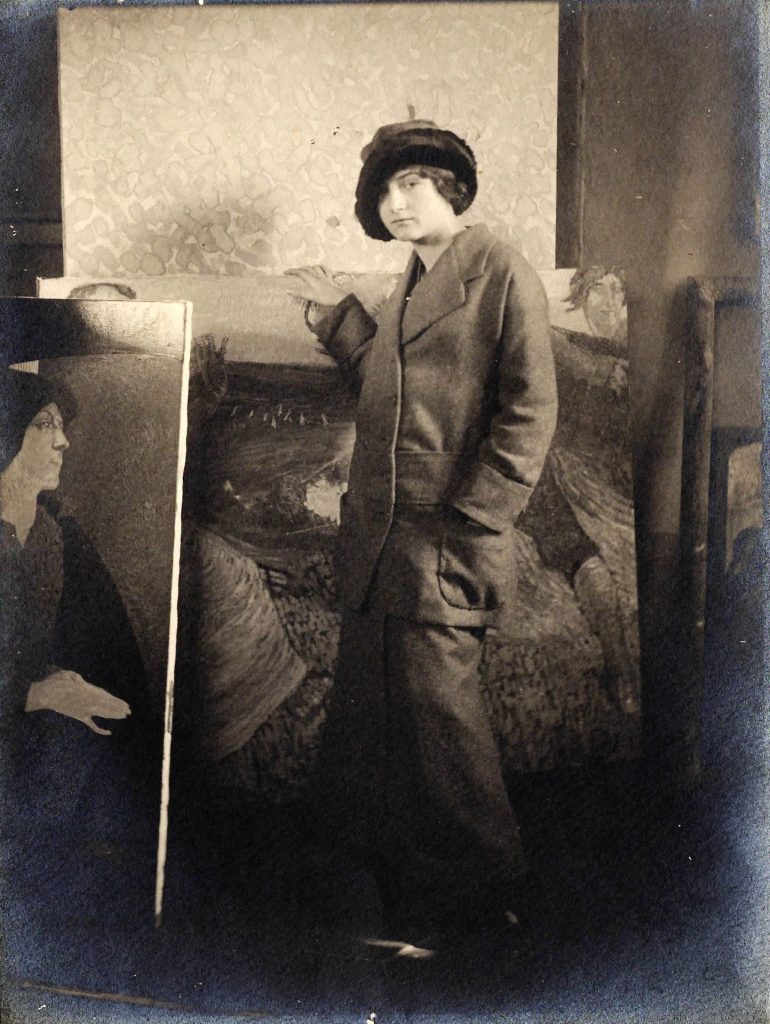

The Italian painter Pasquarosa (1896-1973) was in her teens when she decided that her first name would suffice: meticulously lettered, and often prominent, it appears as a bold decorative element in many of the earliest paintings featured in the Estorick Collection’s revelatory new exhibition Pasquarosa: From Muse to Painter.

Her signature suggests youthful precocity, but Pasquarosa Marcelli’s real motive is just as likely to have been delight at her increasingly accomplished hand. She was illiterate when she arrived in Rome in 1912 to work as an artists’ model, but by 1913, the starting point for this exhibition, she had not only taken up painting, but had begun to read and write.

It’s a tale worthy of a Hollywood biopic, the enthusiastic endorsement of notorious grump, Metaphysical painter and proto-Surrealist Giorgio de Chirico, merely one step on a path strewn with superlatives. To him she was “dear Pasquarosa, a woman of great qualities and a highly intelligent painter”, an accolade echoed again and again by esteemed members of Rome’s intellectual elite.

Writing in the catalogue to Pasquarosa’s breakthrough 1929 exhibition at the Arlington Gallery on Old Bond Street in London, the critic Emilio Cecchi praised her still lifes for “the genial conception and range of tones, the versatility that avoids all monotony, the sensitive qualities of the brushwork.” The exhibition marked the culmination of her journey from uneducated country girl to an inventive and subtly sophisticated painter, and her newfound status as the first Italian woman to have a solo exhibition in London paved the way for still more prestigious engagements, notably her regular appearances at the Venice Biennale from 1930.

Among the many favourable reviews of Pasquarosa’s London exhibition, a piece in the American Magazine of Art outlined her career trajectory in fairytale terms: “Pasquarosa, hailing from Anticoli, the home of the best models in Rome, and herself a beautiful creature, came from helping the art of others to practice it herself, and here is most successful in her flowers which show a real appreciation of colour”.

The author was not wrong to pick up on the remarkable good fortune that seems to have characterised Pasquarosa’s life: once in Rome she soon met the painter Nino Bertoletti (1889-1971), who she would marry in 1915, and the couple shared a studio at the Villa Strohl-fern, an artists’ colony of sorts in the grounds of the Villa Borghese. Bertoletti did what he could to help Pasquarosa with her education, and introduced her into Rome’s artistic circles, where she made true friendships as well as useful connections.

According to curator Pier Paolo Pancotto, Pasquarosa’s personal library is witness to the many friends she had among Rome’s literati. Corrado Alvaro’s Man is Strong, 1938, is inscribed “To Pasquarosa Bertoletti, and her severe irony, which this book may deserve”, while several books by the writer and translator Paola Masino include affectionate dedications from the author. Nino captured some of these friendships on film, too, and the exhibition includes footage from December 1930, of Pasquarosa and Paola Masino in Paris, buying a Christmas tree with the playwright Luigi Pirandello, and Masino’s husband, the poet and playwright Massimo Bontempelli.

Pancotto acknowledges Pasquarosa’s charm and good fortune, but is clear that her rapid success was as much to do with natural ability and hard work as well-placed friends and winning ways. He writes: “gifted with uncommon intelligence, sensitivity and talent, she transformed her life by means of continuous study and dedication to her work.”

In the exhibition, he emphasises Pasquarosa’s independence of vision by contrasting her work with several painted portraits of her by her husband, as well as drawings on display in vitrines.

Where Pasquarosa leaned into modernism, her husband embraced the classicising tendencies of the conservative Novecento movement, lending weight and volume to his figures with brilliantly drawn, sweeping lines and hatching that in paint translates into carefully worked gradations of tone.

Pasquarosa’s flattened, and otherwise distorted perspective couldn’t be more in contrast, and though she objected to being labelled an “Expressionist”, insisting instead that she simply painted the world as she saw it, her pictures imply a deeply personal, emotionally driven response quite at odds with the aloof formality of her husband’s work.

Living at a time when the avant-garde was almost universally preoccupied with ideas of an untutored, “primitive” authenticity, epitomised by the creativity of children, and by non-western “tribal” art, it’s surprising perhaps that Pasquarosa was not characterised as an ingénue, in the mould of Cornish marine painter Alfred Wallis.

But while critics did use words like “naive” to describe her work, the painter and politician Renato Guttuso rather patronisingly praising her “works of such modest ambition but rare skill”, her skill and sophistication seem to have ensured she was treated as an equal rather than a curiosity.

As in 1929, the current exhibition is dominated by floral still lifes, a deceptively homely and unassuming genre that reveals Pasquarosa’s familiarity with the broad currents of the European avant-garde, and specifically the experiments in colour and space of Matisse and Picasso.

A small nude from that year opens the exhibition and while its crude simplicity suggests spontaneity, the detailed pencil underdrawings tell a different story. Similarly, the highly textured paint surface, vivid colours and floral elements, and lack of perspective might indicate her lack of training, except that they remained key aspects of her style well into the 1960s.

With its decorative surface, and gently orientalising subject matter, Still Life with Oranges, Vase and Japanese Box, 1914-15, clearly refers to the still lifes of Matisse. It’s not simply a formal resemblance either, and like Matisse, Pasquarosa creates a tension between the flatness of the canvas, emphasised by the lack of spatial recession in the background, and the more evident volume of the objects set against it.

Often, she disrupts our sense of space through the subtlest of means – the suggestion of a table edge holds two vases of violets in an impossible balance; a rumpled cloth beneath a bowl of zinnias agitates an otherwise static scene. It’s a trick that she continues to develop throughout her career, and in her 1938 painting Primulas, an inconsistent horizon line causes an apparently coherent backdrop to collapse into an anomaly. The presence of animals adds to the uneasiness – a cat sitting on a table, a bird perched on the lip of a jug, “proving” the nature of a surface that other elements cast into doubt.

The exhibition also highlights a striking connection to Winifred Nicholson, a fellow colourist best known for flower paintings and other domestic subjects. Like Nicholson, Pasquarosa paints pots of cyclamen and primulas wrapped in paper, but where Nicholson’s wrappers are diaphanous carriers of light, Pasquarosa’s are more substantial. For her, the wrappers present a further opportunity to render material and colour, and in Cyclamen, c1932-36, the pink paper is so thickly painted that it might be the weightiest material in the picture.

Such diverse influences present a deeply unfamiliar picture of Rome in the years around the first world war. Usually characterised as something of an artistic backwater, the clamour of Futurism increasing as it found currency in the service of fascism, Pasquarosa’s Rome is by contrast a place of cultural and intellectual confidence.

Far from the cultural isolation that befell Italy in the 1930s and 1940s, experienced so acutely by Pasquarosa’s near contemporary, the abstract artist Bice Lazzari, an appetite for dialogue and discovery marked Rome prior to the first world war. It was a mood typified by the four Roman Secessionist exhibitions, organised by a group of avant-garde artists at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni between 1913 and 1916.

Like other more famous Secessionist movements in Vienna, Berlin and Munich, the Roman Secession was internationally minded and anti-establishment, its exhibitions featuring contemporary Italian artists alongside those from across Europe including Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Gustav Klimt and Henri Matisse. Pasquarosa would have seen them all, and in 1915 she took part in the third edition, showing her work alongside well-known international artists and her Italian contemporaries.

Almost a century after her Arlington Gallery debut, Pasquarosa is as little known in London now as she was then, and it is gratifying to see her returning not just on her own behalf, but as a route into an otherwise obscure aspect of Italian modernism.

Exactly how that exhibition came to be is somewhat mysterious: Emilio Cecchi’s catalogue text introduces a further mystery. He writes that Pasquarosa was “the most appreciated” of “the small army of Italian women painters”. On the basis of this latest show, I won’t be alone in hoping the Estorick Collection gets to work on uncovering the rest of the army very soon.

Pasquarosa: From Muse to Painter at the Estorick Collection, Canonbury Square, London, until 28 April