A monumental fuchsia lipstick towers over the cosmetics counter of a department store. Wild leopards and circus elephants tear each other to pieces on top of a factory whose austerity is brightened by Moorish tiles. A luscious candy-striped Victoria sponge rises in tiers over a table laden with cakes.

This is the world according to the artist Pablo Bronstein. A world of extravagant imagery, strangely beautiful and often tempting, but in truth a bitter condemnation of a society which has lost its bearings.

Bronstein has created 22 watercolours and produced a 30-minute film for an exhibition at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, entitled Hell in its Heyday in which he satirises the trappings of conspicuous consumption, and caricatures the remorseless power of industry to fuel that insatiable desire for material gratification.

The introduction to his book is helpful for those wanting to understand what the Argentina-born artist is trying to achieve.

He tells the story of his grandfather, born into poverty in Argentina at the start of the 20th century. It traces his progress and that of the country as it achieved great wealth in the 1940s and 1950s, only to decline into an economic chaos from which it has yet to recover.

Grandfather Bernardo died in the second decade of the 21st century but as Bronstein writes: “The technology that was so prized by my youthful grandfather, the things that were the object of his cult as an electrical engineer, the things that generated wealth and pleasure, are now seen as responsible for much of the ruination and misery of the contemporary world.

“By the end of the 20th century, technology everywhere was viewed as inescapably intertwined with cost in terms of human and ecological destruction.”

And that is what he exposes in this mesmerising show, which is perhaps more relevant today than it would have been had it been shown last year as envisaged. As the museum’s director Bruce Boucher suggests, life is even more dystopian now. “This show is about a hell we can recognise,” he says. “A hell we have been pitchforked into.”

The paintings could hardly be better staged than in the Soane’s. Bronstein admits to a random approach to finding inspiration for his passion for architectural forms and traditions just as Sir John (1753-1837), who was one of the foremost architects of the Regency era, was also an inveterate collector of paintings, sculpture, architectural drawings and furniture.

A glimpse into a gallery room adjacent to the Bronstein exhibition gives a hint of Soane’s influence where designs for grand projects, such as a sepulchral chapel, Court of Chancery and a new House of Lords, are hanging.

Similarly, architect Joseph Gandy (1771–1843) worked with Soane on his projects and produced dramatic paintings such as his grandiloquent design for a Royal Residence (1821) or his atmospheric Architectural Idea of the Hall of Pandemonium from Milton’s Paradise Lost which is very much a forerunner to Bronstein.

Like his famous predecessors, Bronstein uses architectural styles to frame his visions and takes inspiration from pretty much anything that catches his eye, such as posters, holiday adverts, advertorials in Harper’s magazine and works by other artists. He is, he admits, almost impossible to pin down, diving in for inspiration like a magpie, happily admitting to snaffling ideas from random books which lie around him.

He also takes pains in the book which complements the exhibition to provide information and interpretations which are not obvious from the images. For example, there is nothing in the painting Botanical Gardens to suggest that the infant being pushed in a minuscule pram is Bronstein himself, no indication that the blank facade of a shopping mall in Casino Hotel is displaying fashions and home furnishings and frankly you would have to be extremely erudite to realise that the design of the equipment in a car plant is “French revivalist with some elements of Jacobean mannerisms”.

Such whimsical asides have the effect of making the viewer complicit in Bronstein’s picaresque journey to the infernal regions of our 21st-century world.

As the artist writes: “This humble collection of posters… will attempt, unabashed, to sell you a story we already know the ending of.” In other words, to hell in a hand cart, but no doubt one decorated with flounces and furbelows. In pink.

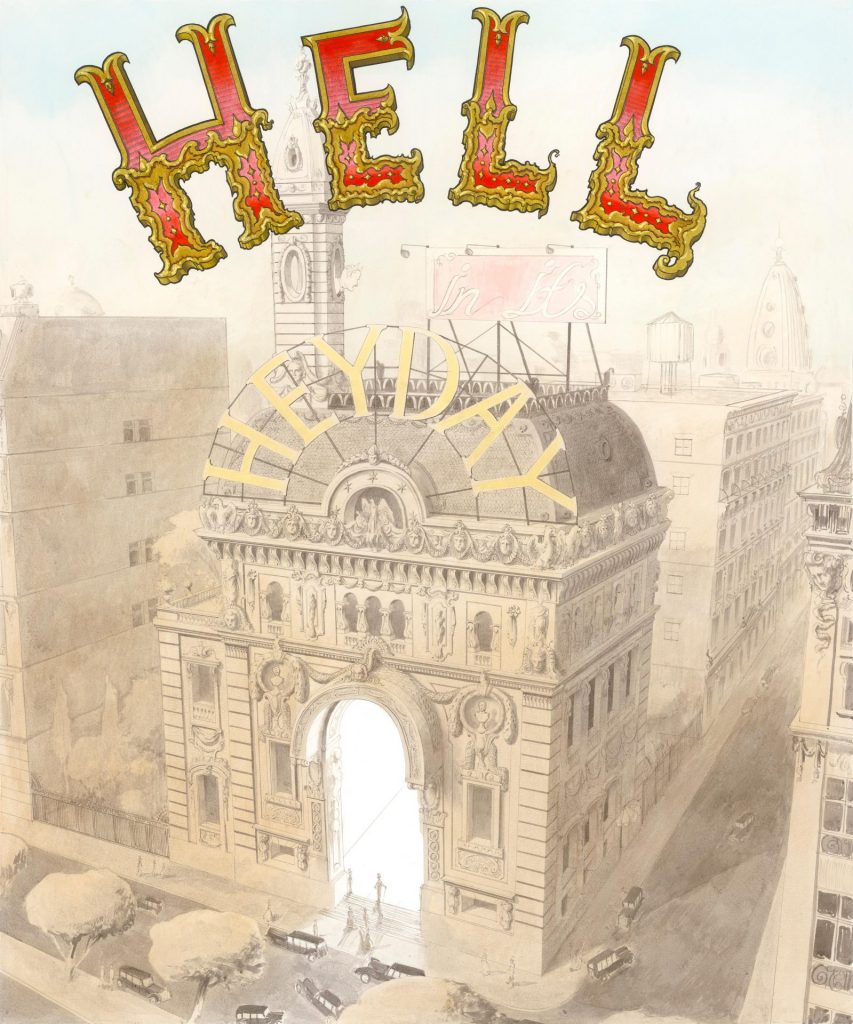

The title piece, Private Members Club, is dominated by a huge billboard proclaiming “Hell in its Heyday” which looms over a pompous establishment which Bronstein, with his eagerness for us to understand every detail, portrays as a converted beaux-arts mansion. The surrounding streets are lined with “swanky apartments” that have replaced stockbroker apartments –another example of his commentary supplementing the image for there is nothing to suggest that visually.

Men in top hats are driven to the club in limos. But are they hearses? Look closely. In a tower just above the Y of heyday, the ghostly figure of Lucifer is leering down.

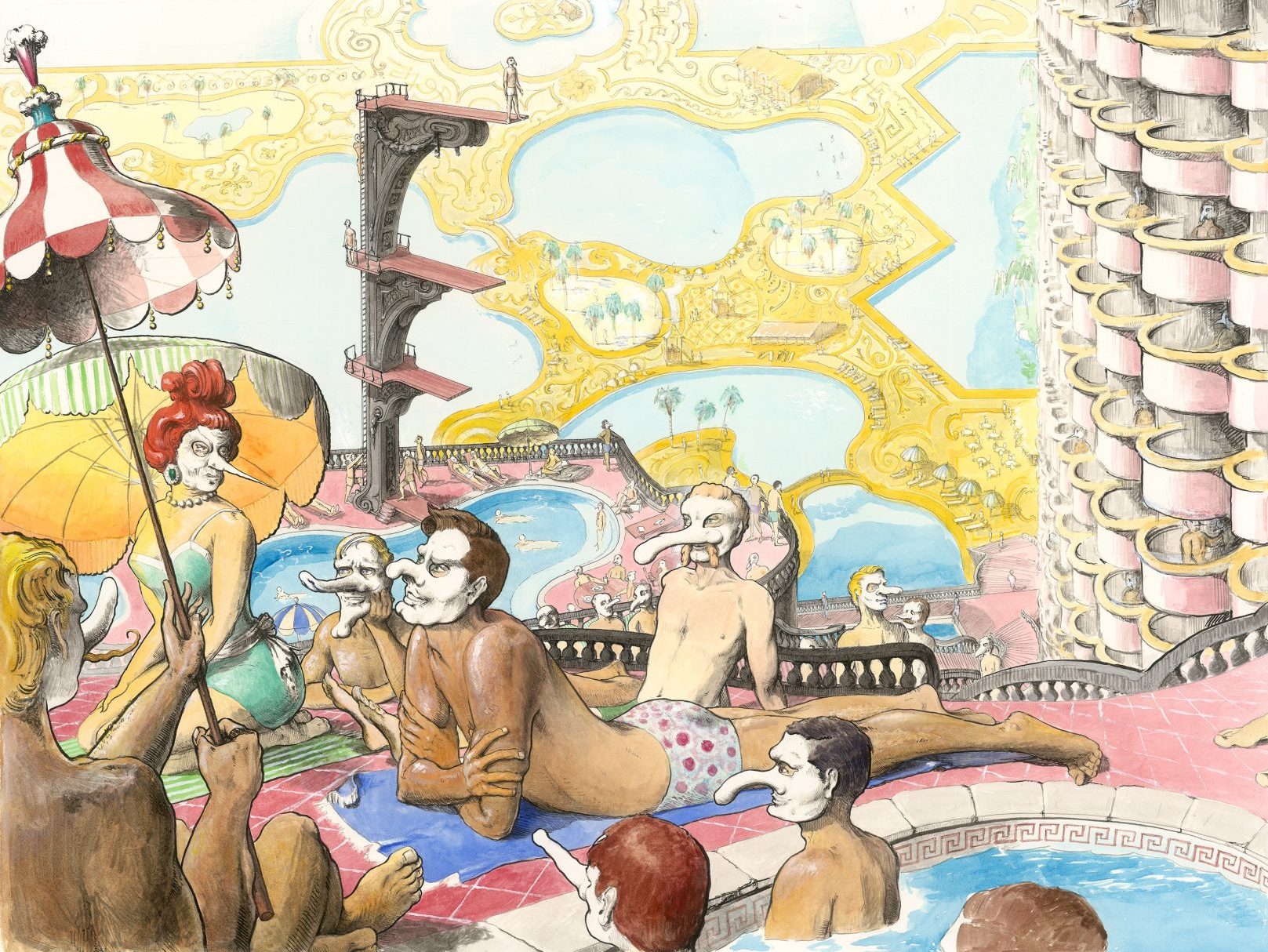

City Centre comprises two paintings. In the first, Flyover and Roundabout, a stark brutalist motorway sweeps past an exotic cupola on one side and a statue of Atlas holding a globe of the Earth on the other. He is supported by what looks like a cake tier of columns in doric, baroque and rococo. There’s a mannerist grotto in there too.

In the companion painting, Atlas has been reduced to insignificance in comparison with the vast Casino Hotel. An art-deco representation of Venus reclines in a shell, milk spurting from her breasts. Just in case the clean lines of the hotel look a tad dull, the building is topped with rococo air-conditioning vents.

“It’s a sickly, over-rich, plum pudding of a thing,” Bronstein says, which is exactly how one would sum up Pâtisseries and Confections in which every treat is listed with the precision of the tea-time menu at The Ritz. The “damask-covered table”, strewn with jam biscuits and meringues, violet blancmange, a Black Forest gateau with a marzipan duck head for decoration, and sugar casters which make a salacious appearance in the film.

Set against a backdrop of skyscrapers which, thanks to the foreshortened perspective, are no bigger than the cakes, helicopters hover, like flies ready to descend and feast on the goodies before they grow stale. Let them eat cake, but be prepared to choke on it.

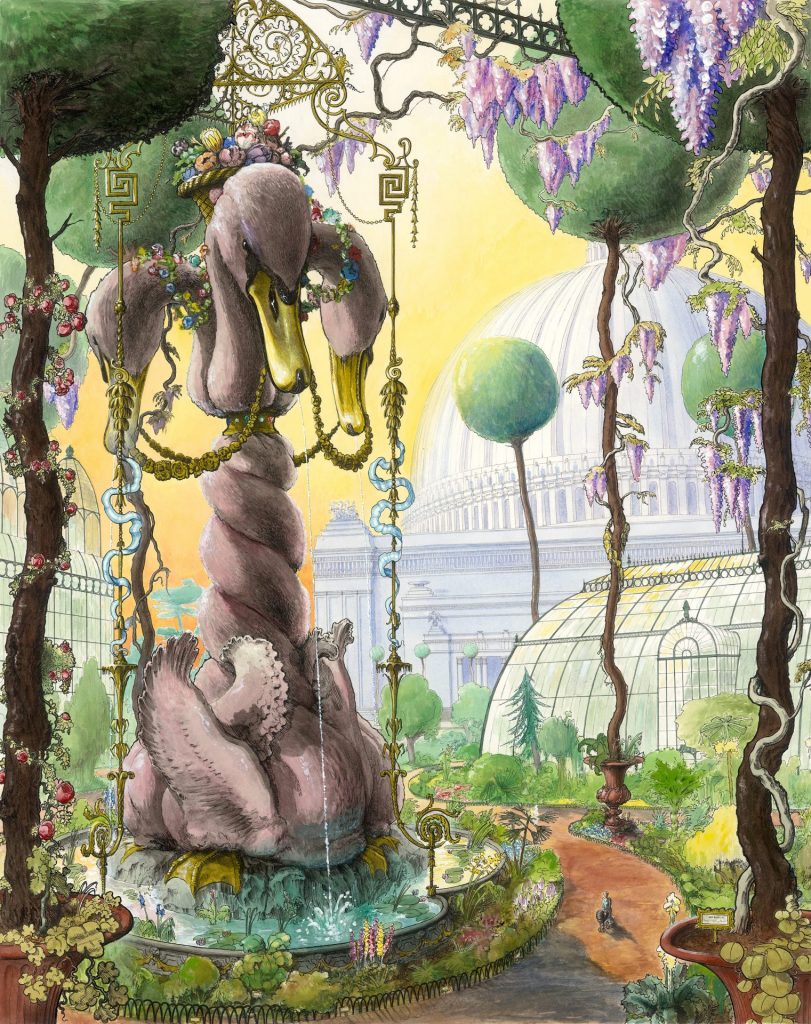

It’s all such a tease. In Botanical Gardens three pink swans with golden beaks emerge from the flowers and shrubs, their necks intertwined. But overshadowing the garden is a domed building, based on the design by Albert Speer, Adolf Hitler’s henchman and architect of the Third Reich.

The department store with its outrageous Piranesi-influenced pillar of lipstick is reminiscent of the perfume-scented chandelier-lit magasins of 19th-century Paris such as La Samarataine. Customers search for bargains as they stroll on undulating stairways holding on to rococo balustrades.

If cakes and casinos symbolise our greed, the means of creating such rampant consumption are also parodied. Rows of oil rigs stretch into the distance above the pumps and the tankers but instead of functional pieces of equipment, the oil barons flaunt their wealth with rigs implausibly decorated in baroque and neo-classical styles.

The grim reality of mining is parodied in Coal Mines in which heavily laden wagons are improbably fetched out in rococo patterns with red roses and ruched swags of gold, blue and purple.

A car plant – the one with the Jacobean mannerist influences – is equipped with terrifying titanium drills which help churn out a production line of cars which goes on for ever.

Just as there are nods to the architecture of generations past, there are references to artists too.

In the unnerving Flight, with its planes falling from the sky to a certain doom, sharp eyes will detect two characters from the brush of Toulouse Lautrec, the characters Goulou and Clownesses who ensnare the planes with their stringy, snaky tongues, while a clown, taken from Georges Seurat’s The Circus, nonchalantly performs on a trapeze amid the carnage.

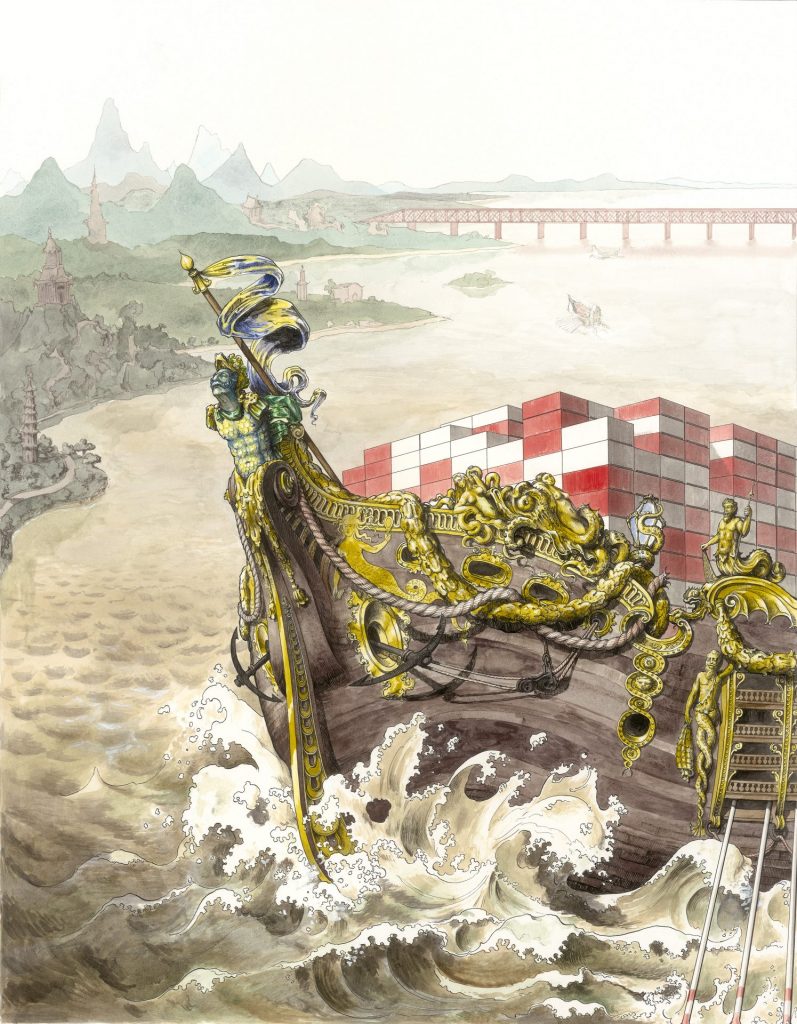

The waves cascading off the bow of giant Roman galley, oars decorated in heavy gilt but laden with modern containers, are executed with the precision of The Great Wave by the Japanese master Katsushika Hokusai while in the background a railway bridge is decorated with a Chippendale trellis.

Of course, the evil-looking lobster, sprawled across a port with a figure of Prometheus atop the light house, owes its provenance to Salvador Dali and his surreal lobster telephone.

That same unnerving juxtapositions are evident in the 30-minute film Boutique Fantasque which complements the alternative universe of the paintings. A smartly dressed woman wearing a hideous gap-toothed mask uses her well-worn sale pitch on a particularly imbecilic customer, known as “the guy who looks like a corpse.”

Using ballet music and the conceits of Commedia dell’Arte, the “sales team” perform in front of massed shelves of an Amazon-style warehouse and a glittering array of musical instruments. The saleswoman employs the tricks of salesmanship – flattery, deceit and innuendo – to sell her tat as the camera lingers on her fingers caressing the undoubtedly phallic sugar casters and mocks the “dead man” by trying to sell him chipped chinoiserie and rusty old kitchen gear.

She sweeps her hand seductively around the rim of a heavy cast iron cauldron. “Plenty of room for the children,” she murmurs. And with a horrible cackle: “Just joking.”

Joking but serious. Crazy but considered. A dystopian world which draws you in only to repel.

- Pablo Bronstein: Hell in its Heyday. Until January 2, 2022, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.