Giuseppe Di Matteo spent the last two years of his young life being taken by his captors to different hiding places around Palermo. His final eight months were in a bunker beneath a field near the Sicilian town named after the same Saint as he was, San Giuseppe Jato.

Giuseppe had committed no crime, yet his father, Santino, had broken the mafia’s rules. After playing a role in killing Italy’s two leading anti-mafia judges, Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, both murdered in 1992, Santino testified against his co-conspirators.

To try to silence him, his accomplices in those crimes took his son. According to the confession of one of the boy’s killers, Vincenzo Chiodo, in 1998: “I told the child to get into a corner, hands above his head, facing the wall… I put the cord around his throat. I pulled it with a strong jolt.” Others entered the room, and one, called Giuseppe Monticciolo, told the boy: “I’m sorry, but your father ha fatto il cornuto” (cheated on us). The boy “didn’t seem to understand anything,” Chiodo continued, “he was very soft, tender, as though made of butter.” Nevertheless: “We poured the acid into a barrel and took the baby… I grabbed him by the feet and… we put him in the acid… I went back down there, and all that was left of the child was a piece of leg and part of his back… I left because of the stench of acid… Then we all went to sleep.”

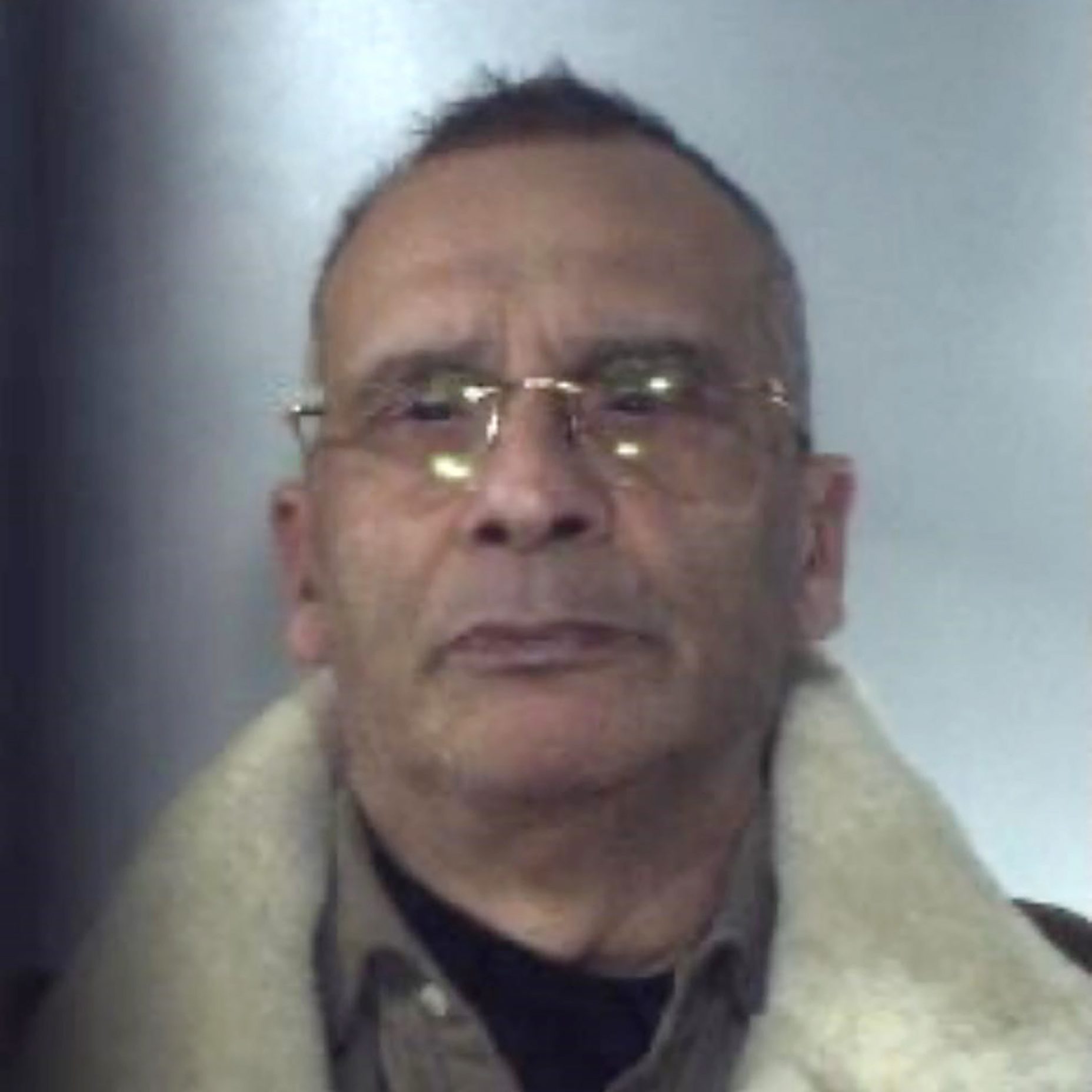

The last member of the death squad that murdered young Giuseppe Di Matteo was arrested this January. His name was Matteo Messina Denaro, and this brutal atrocity was just one in a long list of charges against Messina Denaro. He assassinated Judge Falcone in May 1992, using a half-tonne bomb that also killed his wife and three police officers. He murdered Falcone’s colleague and friend, Borsellino, along with five police officers in Catania the following July. Then, in July 1993, he was behind the bomb at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence that killed five, and another near the Gallery of Modern Art in Milan, also killing five. He was also behind two explosions in Rome, opposite San Giovanni in Laterano and near the Campidoglio.

“We have arrested the last strategist of the massacres of 1992-93,” proclaimed the chief prosecutor of Palermo, Maurizio De Lucia, as he announced Messina Denaro’s arrest. It was a moment of great resonance for those of us who had reported on his outrages. Back in the 90s, I shared an office at La Stampa with the journalist Francesco La Licata, a friend, biographer and journalistic confidant of Judge Falcone. La Licata’s coverage of Messina Denaro’s arrest avoided personal reflection. He was “cold and detached,” he wrote, and a “cruel man”, who wielded “a power held together by consensus rather than by fear… That’s how you can remain a fugitive for 30 years.”

Messina Denaro was finally arrested as he arrived for an appointment at the Maddalena clinic in Palermo – which he had attended since 2020 – to continue a cycle of chemotherapy treatment. “I had expected for a long time that this would happen,” said Borsellino’s brother, Salvatore, “but it is absurd that it took 30 years.”

Messina Denaro was born into a mafia family, son of Francesco “Don Ciccio” Messina Denaro of the Belice clan, at Castelvetrano. He learned to use a gun at 14, and soon became a notorious killer, boasting that he’d “filled a cemetery” all by himself. By the age of 20, his capacity for extreme violence had brought him to the attention of Totò Riina, the mafia boss.

Under Riina’s mentorship, Messina Denaro rose to become part of a quartet of falchi, “hawks”. These were the so-called stragisti – literally, the “massacrists”: the other three were Riina’s brother-in-law, Leoluca Bagarella, Giuseppe Graviano, a boss and notorious killer, and Giovanni Brusca, released from jail in June 2021 to public outrage (the latter two were also party to the young Giuseppe’s strangling).

There is a chilling account of a meeting by the Trevi fountain in Rome in February 1992, between these four, on a mission ordered by Riina: “The moment has come. First: Judge Falcone.” They had rented a Fiat, into which they loaded explosives and a pistol. The idea was to hit Falcone at what they thought was his favourite restaurant in the capital, Il Matriciano. They got it wrong: Falcone preferred La Carbonara, on Campo dei Fiori. The mission had been bungled, and Riina issued another instruction: “You need to come back down to Palermo. We’ve got big things on our hands.” Falcone, his wife and bodyguards were murdered soon after.

When a mafioso called Vincenzo Milazzo expressed doubts about the stragista campaign, Messina Denaro murdered him and strangled his pregnant girlfriend, Antonella Bonomo, a 23-year-old schoolteacher. A few days later, Falcone’s closest colleague and friend, Borsellino, was blown up by a car bomb near his mother’s house in Catania.

Riina was arrested in January 1993 and Bernardo Provenzano became the new head of the mob. His approach was different from that of his predecessor. According to La Licata, under Provenzano, the mafia became “more reserved, more oriented towards lucrative business”. It also sought a rapprochement with the political establishment.

A supergrass called Vincenzo Sinacori described a meeting in 1993 at a resort near Cefalù: present were the usual company of Messina Denaro, Graviano and Bagarella. At one point, Sinacori was asked to leave as a guest of honour arrived. It was a Christian Democrat senator from Palermo, Vincenzo Inzerillo, who was arrested two years later and whose conviction for mafia association was finally upheld by the highest court in Italy, the Cassazione, in 2011. Following that meeting in 1993, under increased pressure after the bombing campaign, Messina Denaro was forced into hiding.

His hideout on the run, and thereby fiefdom, was Campobello di Mazara, between his birthplace and the sea, with its small square, clock tower and economy based around bottling local wine and olive oil – the best samples of which Messina Denaro would generously distribute to other patients at the Maddalena clinic (€13m worth of olive groves were among his seized assets). His final apartment was in the humble Via San Vito, known locally by its old name Via Cb31, according to the town’s singularly numerical address system.

The town’s mayor, Ciro Caravà, was convicted of mafia association in 2011 – there’s little doubt that the entire local clan was at Messina Denaro’s disposal in securing what prosecutors call “pervasive control of the territory”. Last September, a capo of the local clan, Francesco Luppino, described as one of Messina Denaro’s “most faithful”, was arrested.

Messina Denaro began using the alias Arturo Bonafede, not an invented identity or that of a dead person, but that of the living nephew of a known mafioso from Campobello di Mazara. So there were two Arturo Bonafedes at large, and this proved to be one of Messina Denaro’s uncharacteristic mistakes. The authorities kept an eye on the real Bonafede, and they knew, from telephone intercepts with friends and relatives, that Messina Denaro was in need of serial medical attention. They monitored local clinics and eventually noticed an appointment made under Bonafede’s name, even though the real Bonafede had no such appointment. They tried their luck, and got their man. A tape of the moment was played during the aftermath of the arrest: “Excuse me, are you Matteo Messina Denaro?” “Yes, I am Matteo Messina Denaro.”

According to the commander of the Carabinieri, General Teo Luzi, Messina Denaro was captured using the “Dalla Chiesa” method, a reference to his predecessor in Sicily, General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa, who was assassinated by machine-gun fire along with his wife, Emanuela Setti Carraro, in 1982. A partisan resistance veteran, Dalla Chiesa had achieved marked results against terrorist wings of the far right and left, notably the Red Brigades, during Italy’s infamous 1970s “years of lead”. The government then gave Dalla Chiesa the toughest task, appointing him prefect of Palermo in April 1982. The general immediately urged a new and reinforced strategy to confront the mafia.

A drama series about the general and his life is soon to be aired on Italian television, approved by Dalla Chiesa’s son, Nando – a former parliamentary deputy who runs the Observatory on Organised Crime at Milan University. He is also the honorary president of Libera, a network of mostly young people who advise, support and urge resistance to the mafia, cultivate land confiscated from Cosa Nostra, and redistribute retrieved assets.

What was “the Dalla Chiesa method” that the mafia so feared?

“First and foremost,” says Nando Dalla Chiesa, “it is the coordination and centralisation of all we know. It was something my father had learned from, and applied to, his years fighting terrorism. It was a struggle against bureaucracy and compartmentalisation. Everyone and every department had their own territory, their own interests. The ‘Dalla Chiesa method’ was about pooling every piece of information into the same place, and the right place.”

Second, it’s about “control of territory. Being physically assertive, even aggressive in going after mafia presence on the ground, and in terms of intelligence: you need to know what is going on, who owns what – shops, properties, contracts.”

The third element was summed up by the Carabinieri’s head of organised crime, General Angelo Santo, who said: “Know how to wait. Don’t pounce too soon. Follow the target, who they meet, where they go – maximise the results.”

And it worked. Messina Denaro was wearing a €30,000 (£26,500) watch when he was arrested. The contents of his lair, when raided, included designer garments, receipts from good restaurants and sexual enhancement medication. The list of his known girlfriends is long, and he had a daughter, though he never saw her. He seems to have had no problem travelling wherever he wanted: there are traces of him in Marseille, Caracas and even the suggestion that a house was at his disposal in the UK, though there is no evidence that he used it.

He is now held at Costarelle jail in Aquila under an Italian law called 41-bis, a prison regime that heavily restricts communication. It is the nation’s most secure; Riina was there, likewise Provenzano – Messina Denaro’s new neighbours are bosses from the Corleone clan and the Camorra, and commissars of the Red Brigades – though he’ll never have the pleasure of meeting them.

Might he collaborate? La Licata writes: “What will Messina Denaro do now? Difficult to hypothesise: certainly he has a lot to offer and little to ask… And behind the bars of 41-bis, the other bosses fear that the custodian of the mafia’s secrets could spill the beans.”

The arrest was heralded as a landmark “victory for the state” by Italy’s political leaders. The prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, sped to Palermo to offer her congratulations. Her political capital is well served by the arrest, and there is some logic – awkward in liberal and left circles – in a leader accused of neo-fascism claiming an anti-mafia mantle.

Until Falcone, the most effective anti-mafia official ever mobilised against Cosa Nostra was Cesare Mori, “The Iron Prefect”, appointed by Benito Mussolini in 1924. But if anything breathed new life into a mafia battered by fascism, it was the allied liberation of Sicily in 1943.

According to other, more reflective, voices, this may be the end of a chapter, but certainly not the book. The mafia pervades and survives. True: the atrocities of 1992-93 were signs of Cosa Nostra’s weakness, not its strength. It was at the time being overtaken by the ruthless business savvy of the Neapolitan Camorra, and both have since been left behind in terms of turnover and share in the global drug trafficking market by the ’Ndrangheta, the crime syndicate based in Calabria.

Messina Denaro’s arrest must be seen in context of the trial of 345 ’Ndrangheta gangsters in Lamezia Terma, which proceeds under the prosecutorial guidance of Nicola Gratteri, Italy’s current equivalent of Falcone and Borsellino. The ’Ndrangheta’s No 2 boss, Rocco Morabito, was extradited from Brazil last July after 30 years on the run.

All three major Italian syndicates have “super-bosses” still at large, probably in Italian society: Giovanni Motisi, the mafioso from Palermo, Renato Cinquegranella of the Camorra, and Pasquale Bonavota of the ’Ndrangheta, to name but one from each.

This past Christmas and New Year’s Eve in Catania, it was impossible not to pay homage to the Palazzo della Giustizia where Borsellino worked, catching the low morning sun; and the flowers on Via D’Amelio, where his mother lived but his life ended. Even the square where the bus depot is located in Piazza Borsellino. But the city is a delight to be in: crowds of families enjoying public holidays and the traditional New Year’s Day concert in the lovely Teatro Bellini, the bustling food market in Piazza Carlo Alberto under a deep blue sky. Cosa Nostra feels less tangibly ubiquitous in Sicily now than it did back in the 1980s and 90s.

This is partly because of the shift from stragismo to submersione and partly because of courageous and remarkable resistance to the mafia: not only the Libera organisation but also the Addiopizzo – goodbye extortion – movement by shopkeepers and businesses that refused to pay the pizzo demanded by local clans.

Messina Denaro’s arrest was applauded by citizens of Palermo as it happened, the masked special forces hailed as heroes, the judges as crusaders. The president of the Sicilian business federation Sicindustria, Gregory Buongiorno – who comes from Messina Denaro’s fiefdom of Trapani – rightly and movingly praised “the applause and embraces of people on the street, shoulder to shoulder with the Carabinieri”.

But then he added: “We thought he might be dead, or abroad – but instead, one of the most ferocious mafiosi in our territory of Sicily went, undisturbed, to a clinic in Palermo like any other citizen.” And that is the point: an invisible mafia is still the mafia. The journalist Lirio Abbate says: “The Sicilian mafia no longer has the far-reaching grip of syndicates like ’Ndrangheta and Camorra, but it is a metastasis, it keeps regenerating.” Italy’s national anti-mafia prosecutor, Giovanni Melillo, speaks of “co-penetration of the social and economic fabric of Italy”.

“There is less mafia now,” says Dalla Chiesa, “but society is more mafiosa… The clans are fewer and smaller, but their responsibilities are wider. For every real mafioso, there will be children, cousins, nieces and nephews who may not identify as part of the clan but who are financially dependent on it, or its activities, and have some economic relation to it. It becomes hard to know where the line is between mafia and non-mafia. That is the degree to which it is stitched into our society.”

“A solution is not so much change the political culture,” he says, “but create one, since there is no political culture to speak of in Italy.” The worst forms of political corruption are gone. “A figure like Andreotti is hard to imagine nowadays,” he says, referring to Giulio Andreotti, the Christian Democrat leader and seven-times prime minister, widely seen as Cosa Nostra’s ally on high. He was serially implicated in mafia trials, but was eventually acquitted of mafia association. “The way the Christian Democrat Party operated with regard to the mafia is hard to imagine now. That is a victory,” affirms Dalla Chiesa, “our victory”.

The received wisdom is that the decapitation of a clan or cartel destroys or terminally damages it. What actually happens, as demonstrated by the removals of Riina, Provenzano, as well as Pablo Escobar in Colombia and Joaquín El Chapo Guzmán in Mexico, is that the cartel takes the blow, then adapts or even morphs into something else; temporarily weakened, but no less corrosive or pernicious in the medium and long term.

“The bosses get caught, but the mafia continues,” says Federico Varese, head of sociology and professor of criminology at Nuffield College, Oxford, who studies the rhetoric surrounding the mafia. “If we don’t address the reasons the mafia exists, rather than just its existence, we will be back in a few years with another boss.

“Society and government need to recognise”, says Varese, “that the mafia organises local territory. The reason why Messina Denaro could not be found is that he and those loyal to him exercise an extent of control over the Trapani region. They were not prepared to expose or mobilise against him. We have to face the fact that there is a significant part of society that supports the mafia, and then we have to ask why? Because of the failure of politics and politicians to govern – because government is corrupt and inept, and in that vacuum, the mafia governs social-economic relations. This is more important than an obsession with mafia traditions and mafia investigations”.

Varesi makes his point in part through study of the Pagliarelli clan of Palermo.

There’s the case of a chain of shops selling electrical appliances. “It was being preyed on by thieves. The owner calls the deputy boss of the Pagliarelli, and asks him to come down to the shop for five minutes. ‘Sure’, replies the boss, on a wiretapped call. The shop owner shows the boss CCTV footage of the robbers, who are then traced by the mafia and severely tortured. The stolen goods are then returned.”

Another instance concerns a cake shop and bakery – a pasticceria – “which wanted to expand into a pizzeria. A nearby pizzaiolo objected, fearing competition. The baker went to the Pagliarelli clan for help. It happened that the mafia didn’t like the pizzeria that objected, so they arranged for the baker to get his extension licence.”

A smart bar in Palermo had trouble paying the rent. “They called in the mafia, which settled the dispute – in front of an attorney!” But, warns Varese: “Mafia ‘justice’ and charity is a double-edged sword. If you accept it, you are bound to be asked for further, compromising favours.”

Varese continues: “It’s not that the mafia is fair, just that it governs relationships on the ground. It distributes petrol to garage pumps, and food to supermarkets… We have to be careful of mafia Orientalism,” he says, “the exotic don, the uniquely Italian criminal. What we have here is not unique to Sicily, or even Italy. But there is a difference,” he says. “Most of these other corruptions are recent, or rootless. The mafia is not a gang of thieves or corrupt officials, it has been there for centuries, fulfilling the same role. It is rooted in society. It will remain so until it is uprooted from below.”

Ed Vulliamy is a journalist and author