It’s easy to mock an artist who claims she was told how to prepare the world for a new age of civilisation by a high priest from ancient Babylon.

Hard not to be sceptical about a movement inspired by the Mystic Meg cliché of a spirit communicating with two young sisters by knocking.

Yet contact with some perplexing “other world” through the medium of séances, trances and dreams has inspired artists since the Victorian era and it is their work which is highlighted in Not Without My Ghosts: The Artist as Medium at Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool. It’s an appropriate setting. Mystics and fortune tellers have traditionally thrived in British seaside resorts with Blackpool boasting at least 15, including one going by the name Angelic Guidance and another, Leonora Petulengro, “Palmist to the Stars.”

The works, by more than 30 artists, range from complex abstracts, full of dramatic symbolism, to childlike drawings which really do look as if a mischievous spirit has taken hold of a comatose hand and scrawled randomly on a sheet of paper. The singularity of the works is emphasised by a bold decision to paint the walls of the gallery a transcendental pink.

The exhibition includes the visionary heads that came to William Blake in the night, such as the Spirit of Voltaire and the Ghost of a Flea, and moves through the Victorian era to the 20th century with examples such as Fire Head (1966-68) by the experimental Sigmar Polke which was created under the instruction of “higher beings”.

It comes up to date with the likes of installation artist Pia Lindman and Ann Lislegaard who underwent hypnosis before putting pencil to paper.

But it is the Victorian women – and it is invariably women – who capture the imagination, not least because they and their works were born out of an intriguing mix of evangelical religion and mysticism and early stirrings of feminism, though the last of these may be with the interpretation of hindsight.

In the mid-19th century, society was gripped with working-class protests, the teachings of Karl Marx and the stirrings of women’s suffrage. Above all, perhaps, it was disturbed by the theories of Charles Darwin which overturned an entire structure of beliefs about the world and left many looking for a meaning to all the confusion.

Counterintuitively, by assuming the often-covert role of the medium, women found it easier to adopt a public persona and take a political stance without transgressing the social boundaries of the day.

The writer and enthusiastic spiritualist Sir Arthur Conan Doyle declared that the movement could trace its beginning to the small the town of Hydesville in New York State in 1848 where sisters Maggie Fox, 14, and Kate, 11, claimed to have been in communication with a ghost called Mister Splitfoot.

They claimed that every night around bedtime a series of knocks on the walls and furniture could be heard – noises which proved the existence of an otherworldly intelligence.

They invited witnesses to listen as they ordered the spirit to count to five, which it did with five knocks. Then 15. Then the age of their neighbour: 33. They became a sensation only for Maggie, years later, to confess that the sisters used to tie an apple on a string and move the it up and down so that the piece of fruit bumped on the floor in reaction to a question.

Despite the confession, they had caught the imagination of a public hungry to find meaning – or consolation – for their lives.

The society for National Spiritualist Association was formed in 1893 and continues today as the National Spiritualist Association of Churches.

The other international influence on the movement was Madame Helena Blavatsky, a medium who settled in the USA in 1873 having left her native Russia and co-founded the Theosophical Society. She instantly appealed to those weary of established religions and uneasy at an increasingly industrialised society, by communicating with spirits and particularly impressed her disciples with her ability to move objects through the air – even through walls.

She was also an influence on one of the leading artists in the British movement: Georgiana Houghton (1814-1884) whose Chronicles of the Photographs of Spiritual Beings and Phenomena Invisible to the Material Eye was later reviewed by Blavasky in her periodical The Theosophist and which she judged, “A neat and curious volume… the book is full of valuable testimony.” Houghton came to spiritualism late, aged 47, and unmarried, after several of her close relatives died. She was encouraged to attend séances where she learnt the basic skills of automatic writing helped by her “invisible friends.”

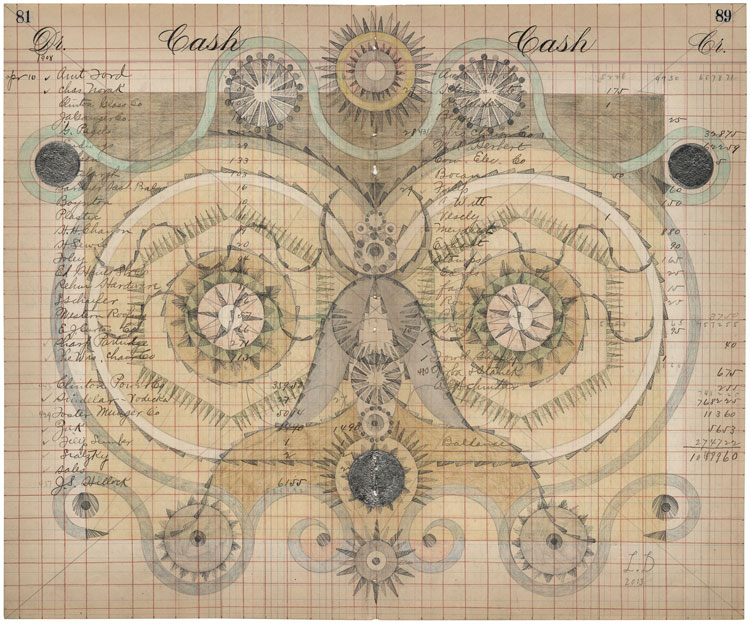

Unlike most spiritualist artists, she did not hide her work away in the clandestine confines of her parlour but, rather, in 1871, staged an exhibition in Old Bond Street, London. A devout Christian, many of the 155 works had titles such as The Eye of the Lord and Glory be to God but the Grundy gallery in Blackpool is showing the floaty, rather beautiful Flower of Zilla Warren (1861) which, Houghton said, captured the essence of her beloved dead sister, and the visceral Spiritual Crown of Mrs AA Watts (1867), a vision of the English Pre-Raphaelite painter, writer and spiritualist.

She admitted that the death of her sister Zilla “so crushed me, that I felt as if I should never again use pencil or brush,” but, with the aid of the spirit world, she recovered – so much so that The News of the World compared her compositions to the “imagination of a canvas of (J.M.W.) Turner’s, over which troops of fairies have been meandering, dropping jewels as they went.”

Anna Mary Howitt (1824-1884) was almost a contemporary of Houghton but from a very different background. Her parents were prominent members of the spiritualist community in London and Howitt became friends with the Pre-Raphaelites William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti and met literary figures such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Elizabeth Gaskell.

She exhibited at the Royal Academy but an ambitious painting, Boadicea Brooding Over Her Wrongs (1856) was ridiculed by the critics who preferred their female artists to paint flowers and birds and images of motherhood. She resolved to struggle on “manfully – or rather womanfully – through… the fogs of bad criticism” but it seems likely she suffered something of a breakdown and gave up exhibiting. Instead she turned to spirit drawings which she explained were created when she was “mentally passive…conscious that her hand was used by some unseen process.”

Her untitled figure of a Madonna like figure surrounded by flames, feathers and flowers is somewhere between the kitsch (by today’s standards) and the powerful while another untitled drawing portrays a sketchy female figure surrounded by swirls, random words and phrases which are mostly unintelligible. Often with the spirit artists there is a common theme of loss. Madge Gill (1882-1961) was born in east London to a single mother and placed in an orphanage aged nine. At 14 she was shipped to Canada and forced to work as an indentured servant but returned to London and became a nurse. She married, but two of her four children died and she suffered the loss of one eye following a severe illness.

It was Gill who took her inspiration from a high priest named Myrninerest who purportedly lived in ancient Babylon. With no artistic training but with his guidance, she produced thousands of ink drawings on paper, card and textiles covered in stars and foliage and often female figures.

Her pain is obvious in her painting, Abstracted Flowers, which is dark and forbidding, almost tortured in its intensity.

Just as the mid-19th century was a time of dissonance and confusion, a similar claim can be made for many moments in history – not least the 21st century.

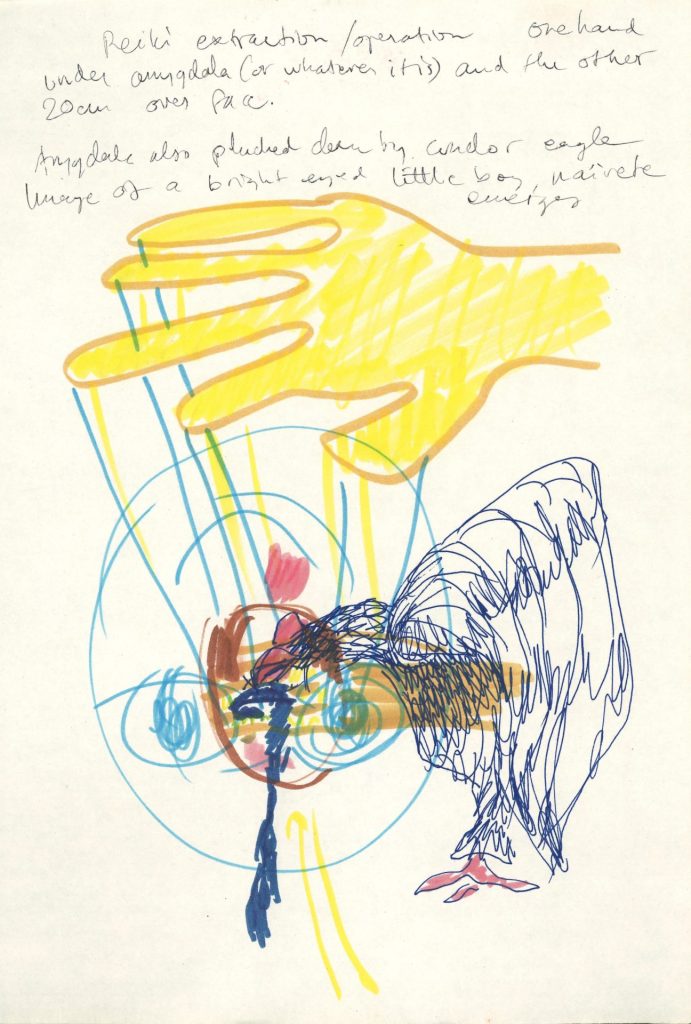

Contemporary Finnish artist Pia Lindman dreamt that she could see the bones of living people and attended a session of a therapy known as kalevala, or bone-alignment, in which she was able to detect energy in the subjects’ bodies which manifested themselves to her as colours, animals and other living beings.

She tells how she “sat down in class and wrapped my fingers around a pair of feet of someone expecting to be treated, I reconnected with the feeling I had had in the dream.”

In Naiveté, a yellow hand seems to guide a condor which is plucking clean the inner-most part of the brain known as amygdala.

In a scribbled note on the drawing she refers to the “image of a bright-eyed little boy, Naiveté emerges”. Baffling stuff.

Her Rocket does indeed look like a projectile and is meant to represent the aura of a specific person while MJPF 29 has a cat whirling into a violent red and blue vortex.

Norwegian Ann Lislegaard made the drawings Liberty Bells during hypnotic sessions between 1993 and 1995 though they are more one-dimensional diagrams than drawings, with little sense that the hypnosis opened her eyes to any great truths. No new age of civilisation apparent here.

What are we make of it all?

Are the works and their creators mere curiosities? Much of the art per se would not pass muster when it comes to staging an exhibition but the context changes that. The sincerity of the artists has to be accepted and gives the work a validity. For example, Lindman’s plummeting cat is a real puzzle but that is what she saw during her therapy sessions and we have to take her vision on face value.

It is, to coin a fashionable phrase, her truth, and one which does not involve playing tricks with apples.

So, not curiosities but worthy of our curiosity.

Not Without My Ghosts: The Artist as Medium, Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool, until December 11. Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea, until March 13. Millennium Gallery, Museums Sheffield, until June 26, 2022