West Berlin is baked into the DNA of Einstürzende Neubauten. Pioneers of the nascent industrial scene, they are a band that could only have been forged in that uniquely creative island city, with all its dereliction, poverty and cold war paranoia.

Forced to fashion unconventional instruments out of electronics and “found” objects such as sheet metal, drills, jackhammers and various detritus due to lack of money, necessity proved the mother of invention. That lack of expensive instruments encouraged experimentation as they embarked on a string of landmark albums in the best tradition of Dadaism and musique concrète.

“It was not really much of an artistical decision,” says founder Blixa Bargeld. “It was simply pragmatic. We did with what we could find.

“I used to think a band like Neubauten could come from anywhere,” he adds. “I didn’t think Berlin played any role. Only with my horizon being broadened, when we started playing in London, or Paris, or New York, I realised how very, very special West Berlin was at the time.

“The trash, the ruins that were still there, the marks of the second world war, all this, I realised much later as being a rather special thing of West Berlin and could not easily have happened in another city. What we did was not possible everywhere.”

Declaring war on musical conventions with their 1981 debut album, Kollaps, they set about a full-frontal attack on the senses, channelling a DIY post-punk ethos to break sonic boundaries. They were even more unrelenting and anarchic live.

Neubauten’s confrontational, destructive stage shows proved incendiary, sparking panic and alarm on a 1984 American tour thanks to a propensity to light fires. At the ICA in London that year, they set about drilling a hole through the stage.

While their sound has developed and grown more melodic and structured, the subtitle of their latest album is perhaps fitting for a band that has always done things its way. Rampen (apm: alien pop music) sees them return to their roots, at least in part, with studio recreations of the live improvisations performed during their 2022 Alles in Allem tour.

Bargeld, who jokingly calls himself a “glam rock god from a parallel universe”, accepts their sound isn’t for everyone, but adds: “I do not really write about things. I play with language, yes, but… I validate myself rather in the fact these very, very few aliens that like what we are doing, some of them can get enough power out of these things I sing or write. That validates what I’m doing.

“I know this is not for the masses and probably nonsense for a lot of people. But that’s just not my problem. I didn’t want to be the part of the mainstream. I wanted to be a different stream that goes in a different direction and comes from a different source.”

That source can be traced back to April 1, 1980 when, as a self-confessed amateur, Bargeld was asked to play at West Berlin’s Diskothek Moon.

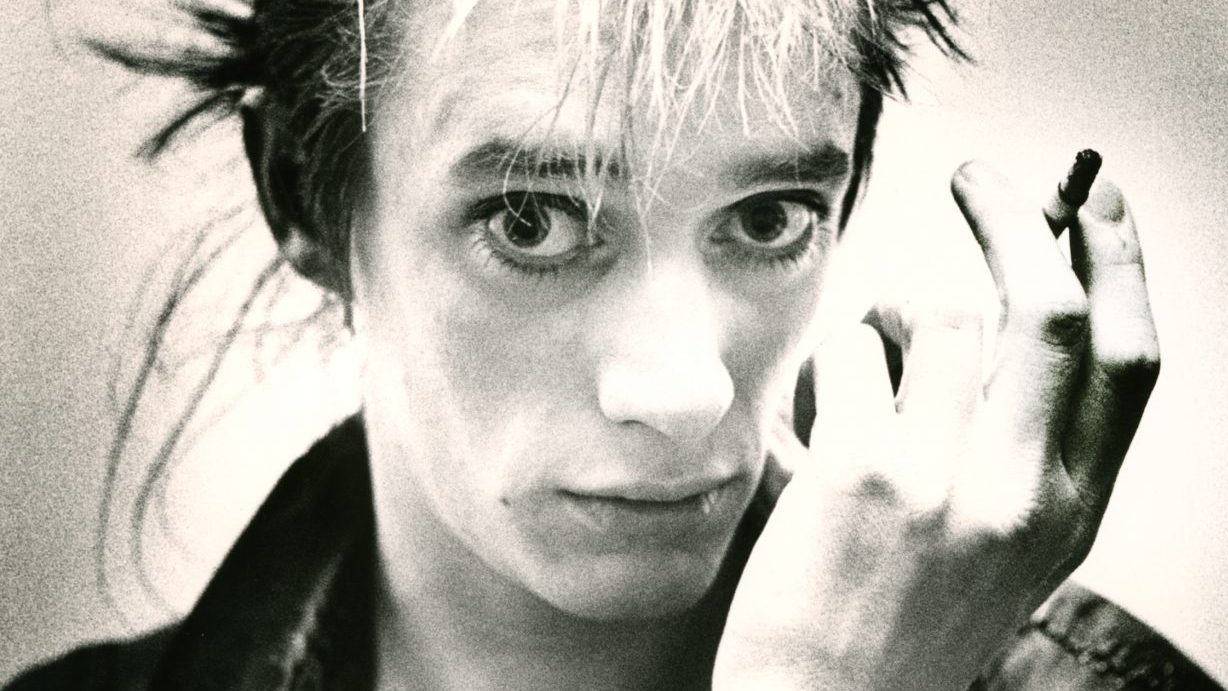

He cut a striking figure in those years. Nick Cave, who later recruited Bargeld as guitarist in The Bad Seeds, first saw Einstürzende Neubauten in concert on Dutch television in 1982 and was instantly starstruck.

Cave wrote later: “He was the most beautiful man in the world. He stood there in a black leotard and black rubber pants, black rubber boots. Around his neck hung a thoroughly fucked guitar. His skin clung to his bones, his skull was an utter disaster, scabbed and hacked, and his eyes bulged out of their orbits like a blind man’s. And yet, the eyes stared at us as if to herald some divine visitation.”

For that first Einstürzende Neubauten gig at Diskothek Moon, Bargeld invited a few friends, including longtime percussionist NU Unruh (born Andrew Chudy) and took their name (“Collapsing New Buildings” in English) from the often-cheap postmodern tower blocks constructed in Germany after 1945. FM Einheit (born Frank-Martin Strauß) joined Bargeld and Unruh to record their debut album, which featured cover art mimicking Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma.

Instead of Floyd’s expensive instruments, fanned out in front of Einstürzende Neubauten were an array of metal pipes around a large drill, a television, and a couple of beat-up guitars. It’s one of several playful nods to classic albums on the band’s record covers. “We may be Germans, but we do have actually some humour,” smiles Bargeld. “There is a lot of humour in Neubauten.”

Alexander Hacke and Mark Chung soon completed the “classic” line-up, but West Berlin remains the other key character in Neubauten’s story.

“It was a very desolate place, a very poor place,” says Bargeld. “It would not have really existed unless there had been a lot of money being pumped into the city. A lot of people came to live in Berlin because of those extraordinary conditions; because to live there was relatively cheap, and you didn’t have to go in the army. That made it very attractive to a lot of people.

“You’d go out at night to some dancing place and somebody with an already prefilled subrental contract would approach you and ask if you could make him a subtenant in your flat. Once he had that, he was exempt from military service. That really was common.”

Bargeld and Unruh were among thousands of Berliners who squatted in barely habitable buildings, deliberately allowed to rot until they could be demolished. Attempts by the authorities to crack down on the squatters’ movement prompted unrest as thousands took to the streets to protest against evictions and searches.

In a moment of subversion and solidarity, Neubauten recognised the squatters’ cause, naming their November 1981 tour of Germany the “Berliner Krankheit” (Berlin Disease) tour, appropriating the disparaging name given to the squatters by the senator for the interior.

Neubauten would soon scale back German tours in the face of anti-Berlin prejudice, and to this day, Bargeld counts himself first a Berliner and second a European, rather than a German.

“The first thing you notice is that basically the punk and alternative scene as it was in West Berlin was much more tolerant,” he says. “There was a diversity. As soon as you were going to Hamburg or somewhere else, everything was soaked in some kind of soccer mentality, a regional chauvinism in the true sense of the word.

“It’s still like that. In 2022, the worst shows we had [were] in West Germany. Still, for a lot of people, we are the men from Berlin. Back in the 1980s, for several years, apart from playing in Berlin and maybe Hamburg, we didn’t play anywhere in Germany. We kept ourselves out of all of that for a very long time.”

They were soon creating controversy further afield. Nothing was out of bounds in Neubauten’s quest for new sounds, with many venues and promoters shocked and outraged by their visceral onstage theatrics.

Says Bargeld: “The fire thing was quite extreme in the US. It took us one slip on a stage in Pasadena, and the manager was held at gunpoint, and three days later, they already positioned people with fire extinguishers on the side of the stage wherever we went.

“After a while, it just became a joke. Nobody in Germany gave a shit about us lighting up an iron bowl on stage, but Americans are really afraid of fire. It wasn’t pre-planned. We didn’t know the reactions would be that extreme at all. That preceded us and at some point we had to give that up.”

Writing in the Guardian in 2007, Hacke recalled their notorious 1984 Concerto for Voice and Machinery at the ICA, in which they planned to leave the stage after digging into the tunnel system underneath the venue. Setting up a cement mixer alongside petrol-driven chainsaws, pneumatic drills and jackhammers, they failed to tunnel out, but left the venue with a large hole in the centre of the stage. Hacke recalled that the euphoria was so intense, “it felt ritualistic, meditative, like we were samurai”.

Their journey since has been one of constant evolution. Bargeld moved away from shouting random words and inhuman screams to writing poetic lyrics. By the time of their notorious Palladium Discotheque show in 1986, the NME reported that they had left behind their “cacophony of industrial instrumentation in favour of massed guitars and synthesised percussion”. A more “conventional” lineup perhaps, but, noted NME, the sound was more focused, effective and more moving. Even so, the show climaxed with flaming pans of fire.

As the 1990s dawned, Tabula Rasa (1993), perhaps their most acclaimed album, revealed a softer side, featuring more electronic sounds.

Bargeld, these days sporting a sharp three-piece black suit with matching feather boa and yellow eyeshade, reflects on their musical evolution.

“The first gig [at Diskothek Moon] I remember really clearly was 100% improvised. Over the years, and with a growing catalogue of recordings, there were, of course, things we could play again that became songs, that became pieces.

“The moment of improvisation never really left us, even still to this day, we still have a space in the set for rampen, an improvisation, but it goes from the other 100% improvised shows to a more refined way of presenting ideas.

“I did start in 1980, or even a bit earlier, saying I can’t play, I am a musical enthusiast, an amateur in the true sense. But I can’t go 44 years later and still say I don’t know anything about music.

“Of course, I learned something with everything I did. To act like I’m still an amateur would be just a plain lie. I know nowadays what I’m doing!” he laughs.

Rampen features metal plates, buckets, amplified metal springs and a shopping cart alongside conventional instruments, as well as a choir.

Adds Bargeld: “It would be a lie to say we play all these instruments now because we can’t afford anything else. We use whatever we want and that includes complete string arrangements to whatever instruments I find suitable to follow a certain idea.”

He has always believed in the power of music to attain knowledge, and has discovered truths through his own lyrics, often after the event.

“It’s always been that way. I follow the conviction I’ll find something in the music I didn’t know before. Sing something I didn’t know. Something that turns out to be true. Or something that at least has meaning.”

He found one key stratum concerning identity, gender and biological determinism running through recent albums, one that reaches a conclusion on Rampen (apm: alien pop music).

The lyrics to penultimate track Trilobiten date back to the early 2000s, an idea germinating since Neubauten’s performance at the 1986 World Expo in Vancouver, when the curator Myra Davies gave him a trilobite fossil as a gift.

“She said, this is from a time before there was gender. The trilobite is older. That leads to Gesundbrunnen, the last song on the album, which is definitely a war song against biological determinism. My child just came out as trans. I had that song already written, but that fired even more.

“So, I had to read a lot. I had to get to terms with the whole idea and I took a rather radical position and that is to be against any form of biological determinism. To kick yourself out of evolution. So, there’s a stratum to do with language, and especially being deceived by language. So, that’s there. Identity, existence, there are some political hints. There’s a lot of cynicism.”

Everything Will Be Fine casts a weary eye over a troubled world, written while Bargeld was having to use a wheelchair after breaking his leg.

“I was in very, very bad shape. I had an extreme case of insomnia, that very much perforates the border between your subconsciousness and your consciousness, so I could make six tapes and every tape would be completely different.

“But the final lyrics I wrote on October 7 after the 8pm news, after the Hamas attack on Israel, and I had a very common discussion in our household. If the Nazis are kind of coming back into power and Agent Orange is back in the White House and the Ukraine war is going to extend, where are we going to go? The cynical answer is there in Everything Will Be Fine.”

Einstürzende Neubauten, who still feature Unruh and Hacke, play the O2 Shepherd’s Bush Empire on September 11 as part of an extensive European autumn tour