Just two days ahead of the 80th anniversary of Auschwitz, tech entrepreneur Elon Musk had a message for Germans: “I think there’s frankly too much focus on past guilt (in Germany), and we need to move beyond that. Children should not feel guilty for the sins of their parents – their great grandparents even.“

The audience he addressed via video transmission, the AfD convention, must have found Musk’s words music to their ears. Germany’s far right – whether in its primitive or more sophisticated form – has long declared war on what they call Schuldkult, the cult of guilt. Demands to “finally draw a line”, a Schlussstrich, have been voiced for decades.

AfD’s then-chairman Alexander Gauland went for a more original approach a few years ago when he called Hitler and the Nazis a “bird shit in our more than 1000-year-old history”.

His colleague from Thuringia, Björn Höcke, demanded a “180-degree turnaround in remembrance policy”, complaining that “we Germans are the only people who have planted a monument of shame in our hearts.” He was referring to the Holocaust memorial near Brandenburg Gate.

If anything, German politics and society has only worked harder to “never forget“, including the private sector which – not always voluntarily – invited historians to look into companies’ archives and publish reports about their involvement in Nazi injustices.

But the challenges are growing. And antisemitism is, too. Anti-Jewish crimes are at an all-time high. When talking to members of the Jewish community, you sometimes hear the phrase “Germans love their dead Jews. Mendelssohn. Heine. They even care for the 6 million who were killed in the Shoah. But what about the living Jews?”

Dr Eva Umlauf is one of those living. When she was a child, the Slovakian poet Ján Karsai once wrote these lines about her:

“The number on your forearm is blue like your eyes,

Like the silent sky above Nováky.

Your belly was swollen like a balloon,

When they found you in faraway Auschwitz.

No one could believe that you would live,

That you would return,

To bear witness to your broken home.”

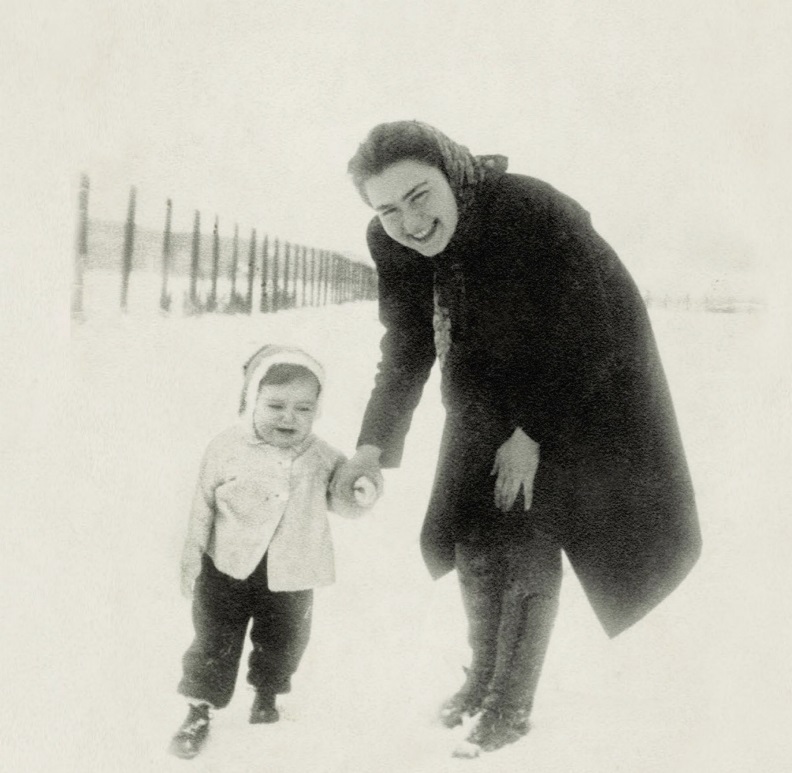

Mrs Umlauf, born in 1942 in the “Labour Camp for Jews” Nováky, was deported to Auschwitz in November 1944 with her parents. She only survived, because the train had technical difficulties, arrived late – it became the first train whose “passengers” weren’t immediately murdered, because in those few days’ delay the SS had started dismantling the gas chambers, to destroy evidence of their crimes.

She will be one of the around 50 survivors to officially commemorate the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz by the Red Army. King Charles, the Bundespräsident and international statesmen will be at the Auschwitz memorial, too. But the focus is on the ever fewer survivors.

“We want to show how strong we are,” the 82-year-old told me before leaving Munich. “But we aren’t strong; we are old. The children from back then. Still, I see it as my duty to go there for as long as I can. To the place where so many lie dead.”

Two years ago, we visited the memorial site together. “Auschwitz is a cold place,” the former paediatrician told me at the time. “Cold – both outside and inside yourself. Make sure you wear something warm.”

Between 1940 and 1945, 1.1 million people were murdered in Auschwitz alone.

And today? “Eighty years on, we have antisemitism in Germany once again. Actually, it is worse than antisemitism. It is Judenhass, the hatred of Jews,” says Eva Umlauf. Since 7 October, it has become worse. “More open. More visible. The Jew-haters are no longer afraid.”

But she is afraid. In New York, when visiting her son and granddaughters, she made detours to steer clear of Columbia University campus on her morning walks. In Munich, where she lives, she is afraid to wear her Star of David openly. Afraid to read the Jüdische Allgemeine on the underground: “What do I know who might sit there, facing me?”

For a few years now, the weekly paper has only been sent to subscribers in plain envelopes, “so that no one – not the neighbours, not the postmen – knows we are Jewish. That’s how far things have come again.”

When the 12-year-old son of friends wore his kippah openly, she asked him whether he didn’t wasn’t afraid. “Did your mum not tell you this is dangerous?” The boy, taking Thora lessons for his Barmizwa, replied cheerfully: “God will protect me.” Umlauf sighs: “Such a little lad – what could I say? That I don’t know where God was in Auschwitz?”

As written in the poem, Eva Umlauf continues to bear witness, particularly in schools. “Not to instill any feelings of guilt – these young people can’t be blamed for what happened. But they need to know what happened. So it never happens again.”

Society must find a way to keep this knowledge alive without the survivors. Will it succeed? Eva Umlauf has her doubts: “They are working on holograms of survivors, video testimonials. But it won’t be the same.“ Still, she remains a Zweckoptimist, a “pragmatic optimist.”

Her memoirs, The Number on Your Forearm is Blue Like Your Eyes, published in 2021, recount the horrors that Nazism inflicted on her family. The book was released in an English edition in 2024. Elon Musk should read it.