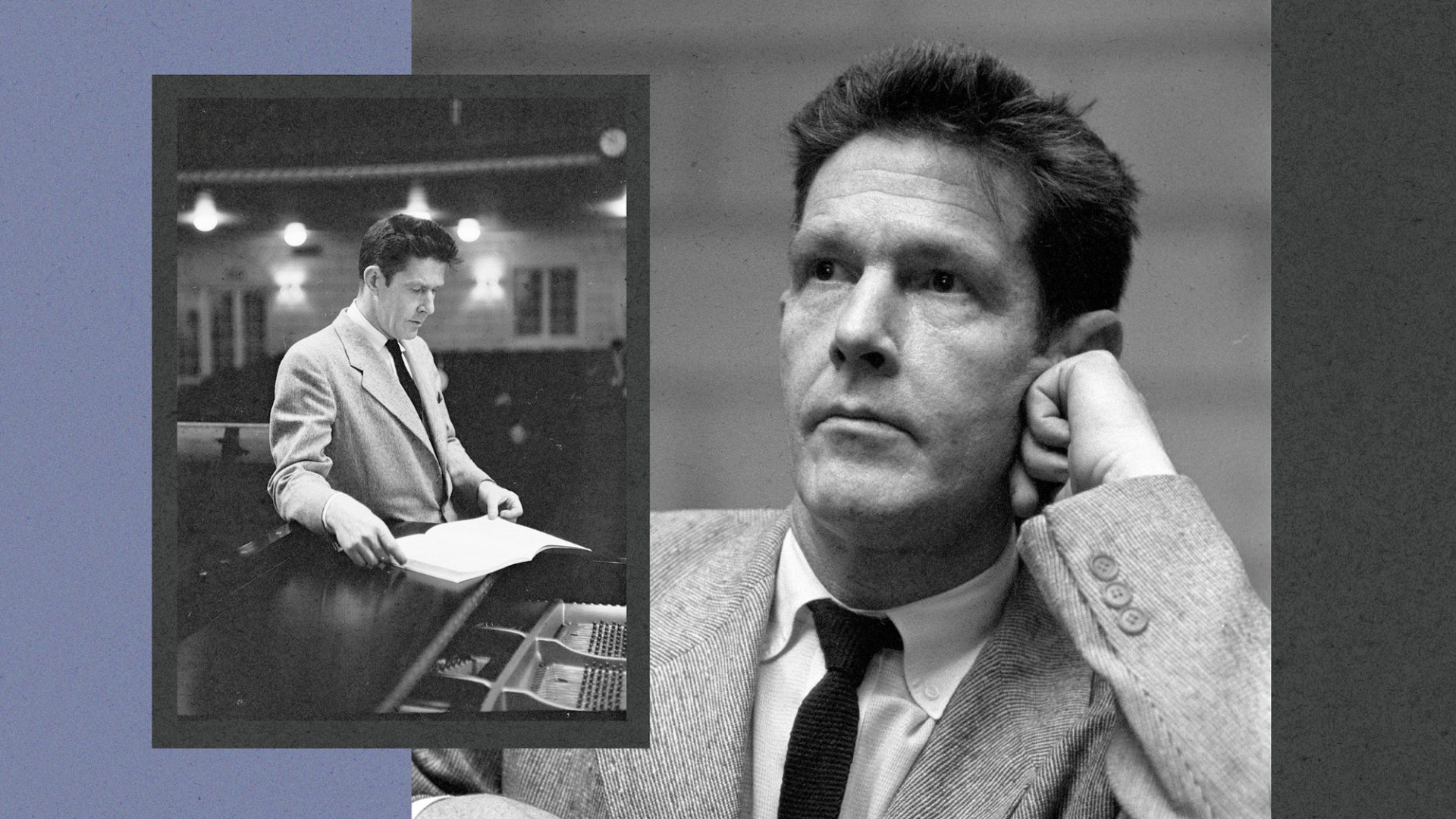

In 1952 the avant-garde composer John Cage premiered 4’33” – perhaps the most philosophical of compositions. Consisting of 4 minutes and 33 seconds of silence, or rather of the ambient sound that can be heard while the piece is being performed, it is by far his most famous work.

“Performed” is a controversial word here, but Cage was clear that this wasn’t purely a conceptual piece and gave instructions that it should be played (or rather not played) on any combination of instruments. The composition has three short movements of different lengths. Each performance of 4’33’’ is different because of the different ambient sounds caused by different acoustics, different musicians, a different audience, and different noises coming from outside the performance space.

There’s a choice of live performances of 4’33” available on Spotify, and they vary considerably. As of last week you can also download Is This What We Want?, a whole album of recorded ambient silence in the style of Cage. Its tracks are labelled “The” “British” “Government” “Must” “Not” “Legalise” “Music” “Theft” “To” “Benefit” “AI” “Companies”.

Unlike 4’33”, which was influenced by Cage’s interest in Zen, Is This What We Want? is a protest album. It was released by a collective called The 1000 Artists: over 1,000 musicians and groups, including Annie Lennox, Damon Albarn, and Kate Bush, objecting to proposed changes to copyright law which would give AI companies far greater freedom to use other people’s music in training their algorithms without paying them royalties or acknowledging the source.

Although there’s a proposal for musicians to be allowed to opt out of their work being exploited in this way, that doesn’t seem like a strong protection. The tracks of Is This What We Want? were recorded in empty studios and other performance spaces to underline the consequences for musicians of allowing AI companies this kind of freedom.

Somewhat ironically, there is no mention of John Cage as the inspiration. But he surely is. It’s worth noting that Cage’s publishers Peters Editions have previously argued that some kinds of silence can be copyrighted. Perhaps they will again.

Back in 2002 they lodged a claim for royalties against Mike Batt (he of the Wombles theme tune) after he’d included his own A One Minute Silence on an album that topped the classic charts in 2002, and cheekily credited it to Batt/Cage. Reports at the time suggested that Batt had settled out of court for this joke by paying the Cage estate a six-figure sum.

But the composer, who declared that his own piece was much better than Cage’s because he’d managed to say in one minute what took Cage over four, later revealed that he’d turned an optimistic copyright claim into a publicity stunt and had paid just £1,000 to the John Cage Trust as a gesture of respect to Cage. Peters Editions did, however, make the point that they believed the concept of a silent piece is “a valuable artistic concept in which there is a copyright”. Batt’s use of Cage’s name in the credits, however, was probably what tipped them over into calling their lawyers.

The 1000 Artists are certainly right that musicians’ livelihoods would be threatened by any loosening of copyright laws. From the AI companies’ perspective, they are simply resisting the direction of travel of history. For them, UK copyright law is an obstacle that is preventing creative use of AI in a post-ChatGPT world.

Perhaps whoever came up with the idea of bypassing current copyright restrictions thought it would unleash a new version of Cool Britannia, but it’s not obvious that a love of music is driving them. Making it all but impossible for composers and musicians to earn a living from their creativity doesn’t sound like progress. AI might be transforming how music is made, but we shouldn’t let it destroy the human world of music-making overnight.

Copyright is always a compromise. It’s a way of striking a balance between creators’ and users’ interests and providing legal redress against piracy and other unfair exploitation of intellectual and artistic contributions. Sometimes it serves the publishers of creative work better than it does the creators. It is constantly in flux and under challenge.

New technologies prompt new laws. AI is, by its nature, parasitic on content, but that doesn’t mean that we should make it easy for it