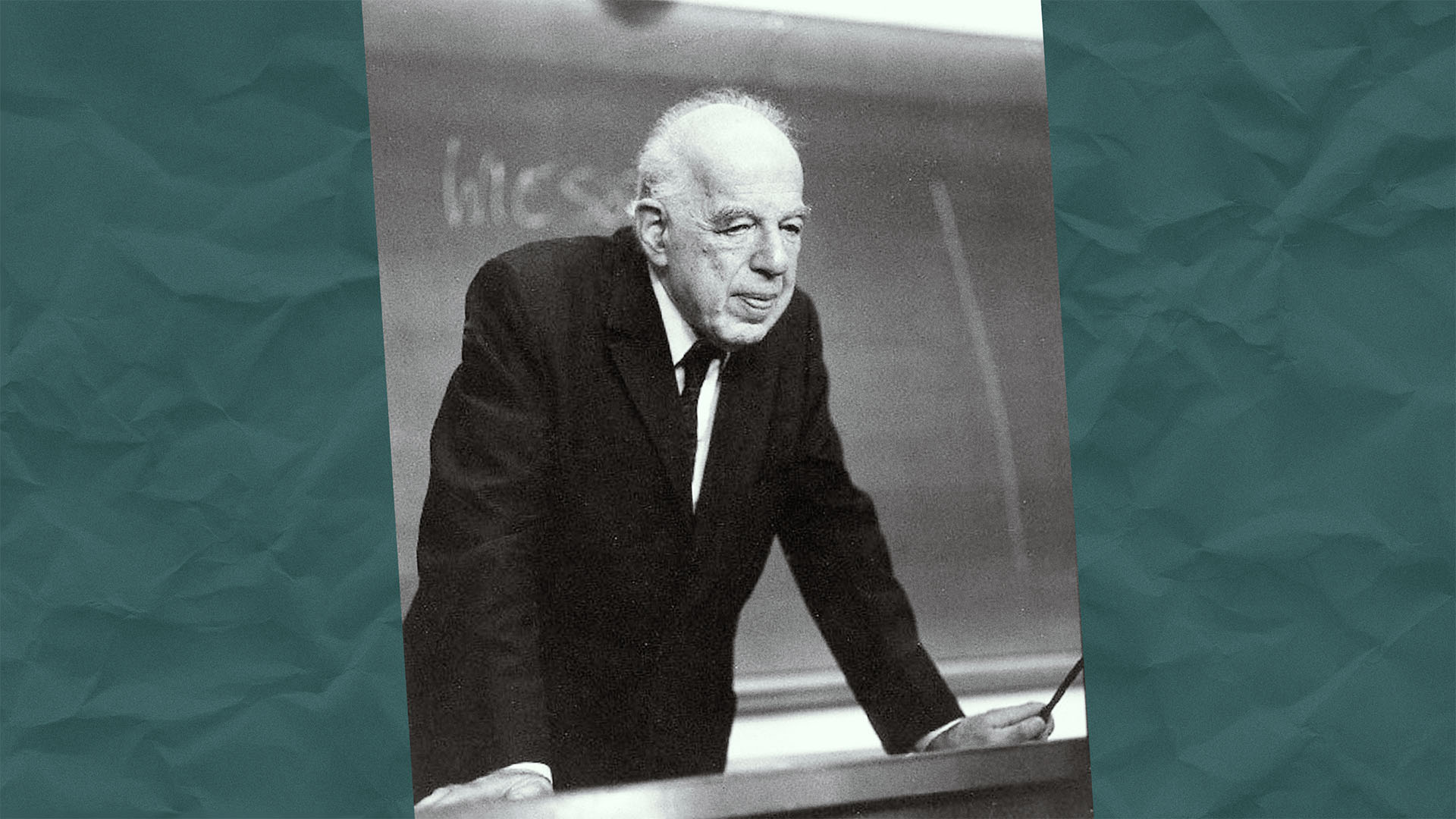

The great Viennese art historian and philosopher of art Ernst Gombrich, whose birthday was on March 30, came to England in 1936. Like so many emigré intellectuals of his generation, he was fleeing Hitler.

His family was originally Jewish but had converted to Protestantism in the early 20th century. That wouldn’t have bothered the Nazis – from their perspective they were still Jewish. Gombrich left Vienna two years before the Anschluss, with all that would have entailed. Austria’s loss was Britain’s gain, and he lived here until his death at the age of 92.

Gombrich was an exceptional communicator and a genuine polymath. After completing his PhD at the University of Vienna, finding it difficult to get an academic post, he wrote A Little History of the World in a very short space of time. His publisher asked him to produce the manuscript quickly, and, remarkably, Gombrich managed a chapter a day.

Perhaps this was the energy of youth (he was only 26), or, more likely, he was driven by financial necessity. He researched by day, wrote swiftly by night, and then read the chapters back to his wife-to-be, Ilse, on their Sunday outings in the woods near Vienna.

A Little History of the World was published the year Gombrich left Austria. It was an immediate but short-lived success. Although he wrote it for children, Gombrich didn’t hide the bleaker side of his subject: “The history of the world is not, sadly, a pretty poem,” he wrote. Presciently he continued, “it is nearly always the unpleasant things that are repeated over and over again.”

Despite that, his humanism shone through. Soon banned by the Nazis for being too pacifist, A Little History of the World only appeared in English in 2005. It quickly became a bestseller. I was honoured to be invited to write A Little History of Philosophy in the Yale University Press series that Gombrich unwittingly instigated, but he was a very hard act to follow.

Gombrich had an even bigger success with his other popular book, The Story of Art, first published in 1950. Still in print 75 years later, that primer in the history of western painting, architecture and sculpture has sold more than 6m copies and been translated into numerous languages. Part of what made Gombrich such a compelling writer for a general audience was his curiosity about everything and his contagious passion for the art he loved.

He never stopped thinking about pictures. This, and his friendship with another great Viennese emigré, the philosopher Karl Popper, led to his original and stimulating Art and Illusion, published in 1960, his most philosophical book.

Gombrich wanted to understand the “riddle of style”: “Why is it,” he asked, “that different ages and different nations have represented the visible world in such different ways?”

His answer, in some ways, mirrors Popper’s account of science as a series of conjectures and refutations. In representational art, rather than simply drawing or painting what they see, according to Gombrich, artists approach the world through the existing schemata that are their cultural inheritance, the formulas that pre-exist for representing reality. The artists then try to match these against the visual world, modifying the schemata accordingly. This making and matching is a kind of testing against reality.

But he didn’t just investigate art from the perspective of makers. One of Gombrich’s key insights was the part played by viewers’ expectations and knowledge, a phenomenon he described as “the beholder’s share”. These significantly determine what they can see in a picture.

This is most apparent in trompe l’oeil paintings set up to trick viewers into believing they are looking at, for example, a fly on a painting, or broken glass covering a drawing, when these are all painted illusions. Viewers used to seeing such things take them for reality and not depictions, tricked by the artist who has anticipated that projection.

Gombrich’s explanations of illusion and the beholder’s share fit well with a contemporary model of perception known as predictive processing, an approach based on empirical research on active brains. The neuroscientist Anil Seth, for example, has emphasised the degree to which we construct reality and don’t simply perceive what’s in front of us.

Seeing isn’t a matter of passively absorbing information that we then process. Rather, the brain acts as a prediction machine that hallucinates reality, constantly revising its best guesses in the light of new information coming in from the senses. Gombrich would have agreed.