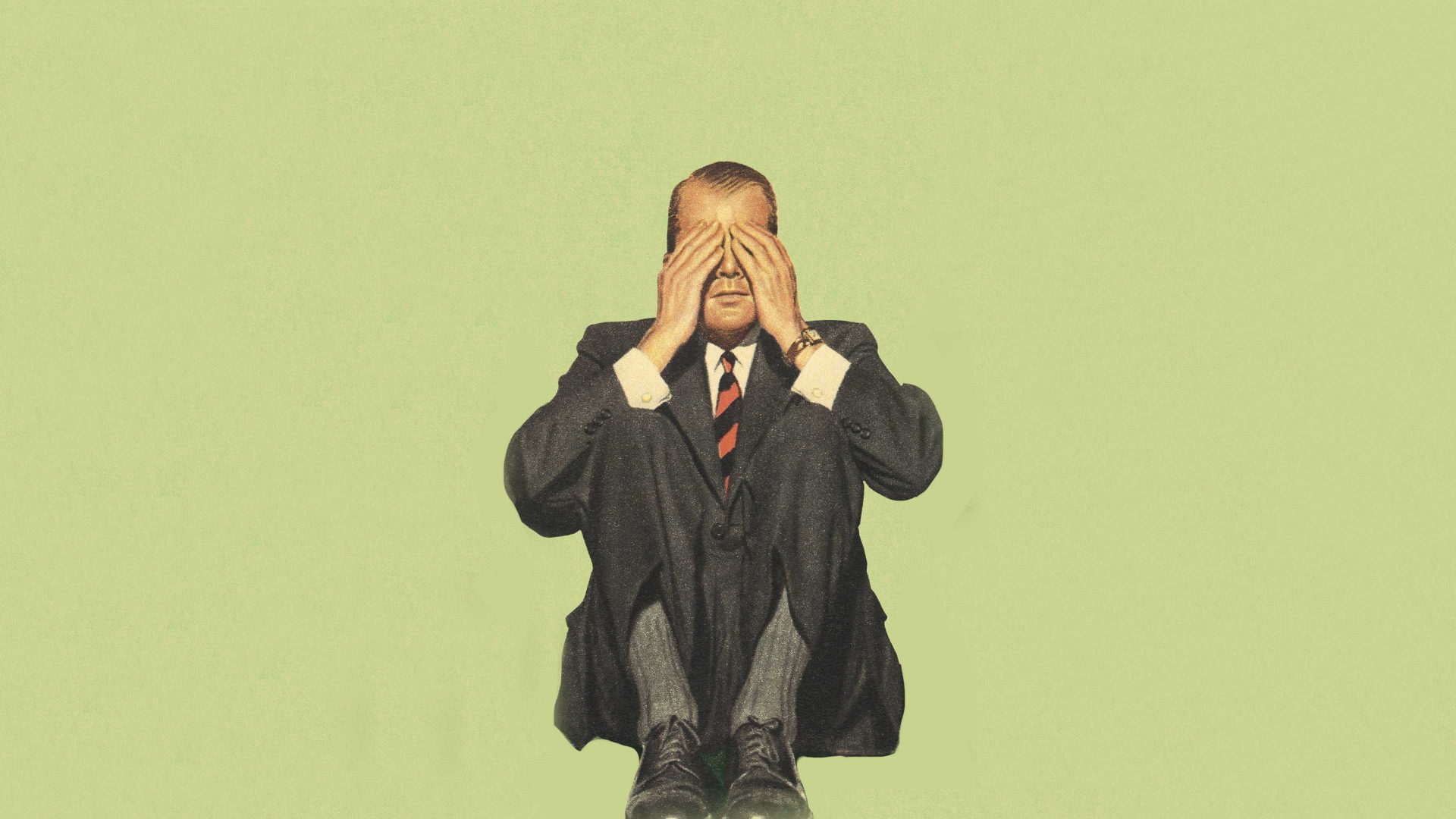

There is something attractive about shying away from reality when things get too grim. Sometimes it’s a matter of psychic survival.

In The Birth of Tragedy, Friedrich Nietzsche suggested that the truth about the nature of reality if confronted directly would make life unbearable. Don’t stare into the abyss, as that will destroy you. It’s only by maintaining some illusions that life remains liveable at all. If he is right, the question is, which ones?

The last few weeks have made shying away particularly alluring. Do we really want to know all the details, the truth about the horrors that have been happening in Israel and in Gaza, or in occupied Ukraine? Do we want to watch videos of terror?

If we could imagine what it is like to be a victim of bombing, starvation, rape, and torture, how could we go on living? At the same time, turning away to watch an endless stream of puppy videos or focusing on TikTok influencers instead of the news seems to be immoral.

In a famous thought experiment known as the Experience Machine, the philosopher Robert Nozick imagines a virtual reality device that would give you the illusion of fulfilling your desires, whatever they happen to be. Most people would plug in for a few hours, but he thinks that few people would sign up for a whole life of constructed and illusory imagery. Nozick believed that many of us want something more than psychological satisfaction: we want to be in touch with reality, and connected with it, not living in a pleasure-filled fantasy world where all our dreams are realised.

But do we? It seems more likely that many of us are paradoxical here. We want to know the truth, we want to know what’s going on. We don’t want to be like those prisoners in Plato’s metaphor of the cave, looking at flickering shadows on a wall and taking that for reality.

But at the same time, when the truth is terrible enough, we really don’t want to see it, or at least not in every detail. The cave can be comforting. We want to get beyond the world of manufactured appearances, but also find some avoidance necessary for self-preservation.

I’m torn here, too. Intellectually it is easy to say that we all have a duty to know as much as we possibly can about atrocities taking place in other parts of the world.

Humanity is more interconnected than ever before, and our governments are taking stances on complex disputes happening thousands of miles away. World events are often relevant to our local lives. What happens in Taiwan can have repercussions in Sidcup. So turning away completely, or retiring to a protective bubble, is not the answer, even for people who are particularly sensitive.

But how much detail do we really need to take on board? Not everyone is temperamentally suited to confronting intense suffering and violence. Each of us has to find a sweet spot between knowing enough and knowing too much.

I am pleased that some people are meticulously recording and analysing atrocities, but am also relieved that there is a division of labour here – that we don’t all have to do this at the same level.

I remember trying to read Martin Gilbert’s history The Holocaust. Elie Wiesel, a survivor of both Auschwitz and Buchenwald, described it as a book “that overwhelms us with its truth”, and declared, “this book must be read and reread”.

Although I was able to watch Claude Lanzmann’s documentary film Shoah twice, albeit through tears, I found Gilbert’s book impossible to read. That was my limit. The accumulation of eye-witness testimony of cruelty and suffering was too intense, too much for me.

I want that book to exist, and I want it to be read. I want Holocaust historians to record and analyse every aspect of those sickening events and try to explain how ordinary people came to perpetrate them. I even want to have read the book myself. But I just can’t.

Aristotle thought that every virtue lay between two vices. The virtue of generosity lay between greed and being a spendthrift, for example, and courage lay between cowardice and foolhardiness.

Perhaps there is a middle way for the virtue of being connected with what is happening in the world, too – one that lies between a perverse enjoyment in other people’s suffering and being completely destroyed by it. The difficulty, as with so much in life, is getting the balance right.