The phrase “heat of battle” might have been made for Trafalgar. In humid conditions, stripped to the waist like his colleagues, an 18-year-old sailor named George King worked and watched as Nelson thwarted a French and Spanish attempt to gain control of the Channel and pave the way for an

invasion of Britain.

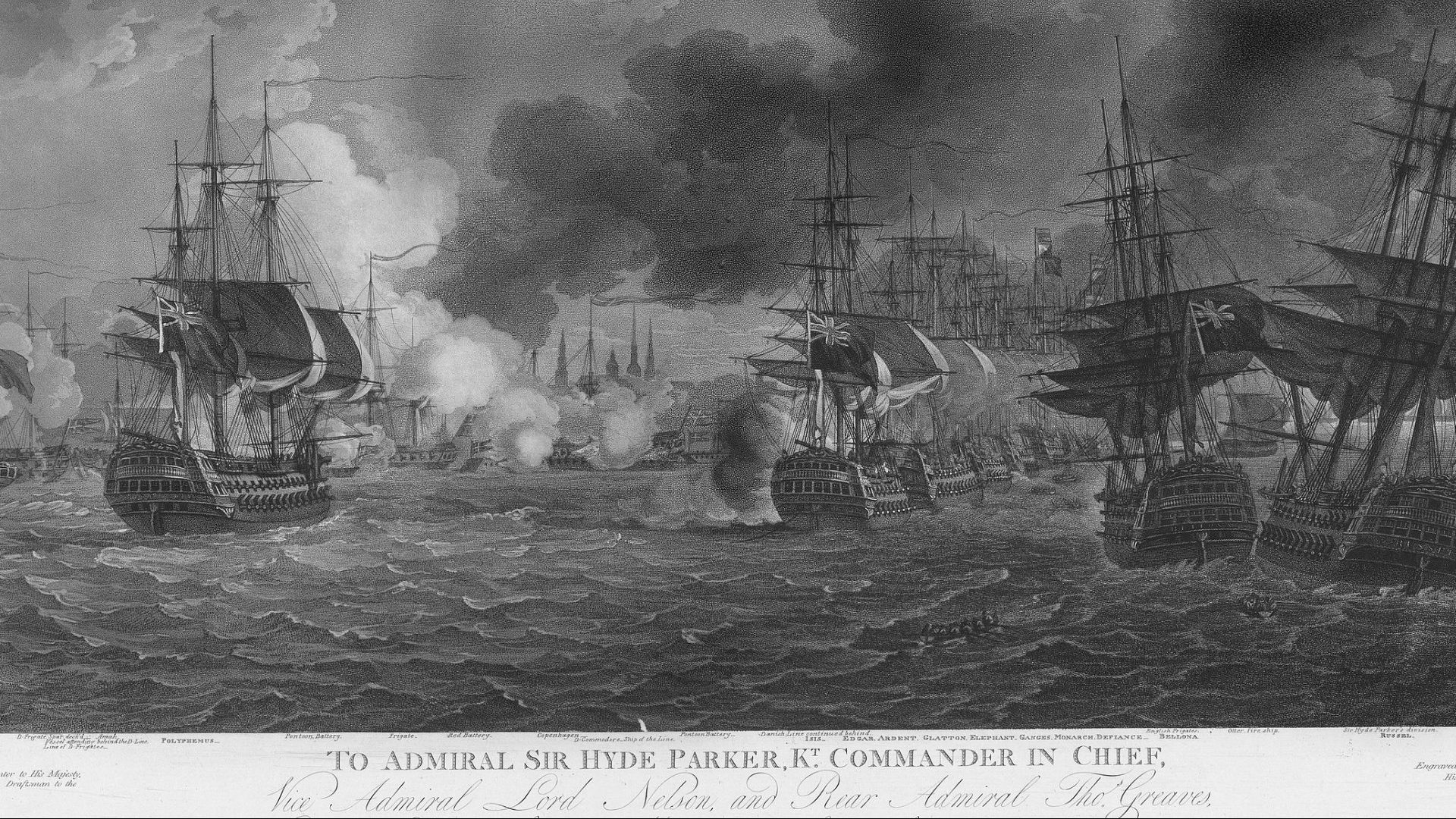

By the end of the day – October 21, 1805 – Nelson’s fleet had sunk or captured 22 of the enemies’ 33 ships. The Royal Navy took over 7,000 prisoners, and another 4,300 were dead. Nelson perished on the Victory, but secured his place in history. And George King committed it all to memory.

It is his extraordinary story that is at the heart of an exhibition at the Foundling Museum. It’s a story that reads like a Boy’s Own adventure of hardship and danger, and quite a few scrapes, played out on the high seas and alien continents.

It began in the summer of 1787, when an unmarried mother named Mary Miller wrote in desperation to the governors of the Foundling Hospital in Bloomsbury, London. She explained that she was “a very Great Object (Of Charity) having had the misfortune of having a Child with a young man who has Quitted her and Child leaving them in the most Extreme misery…” and she claimed that she had no way of “maintaining herself nor Child.”

Mary’s appeal was heard and her name went into a ballot to see if her plea would be accepted. She was in luck. Her son was one of nine chosen, given the number 18,053 and straight away sent off to live with a wet nurse in Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire.

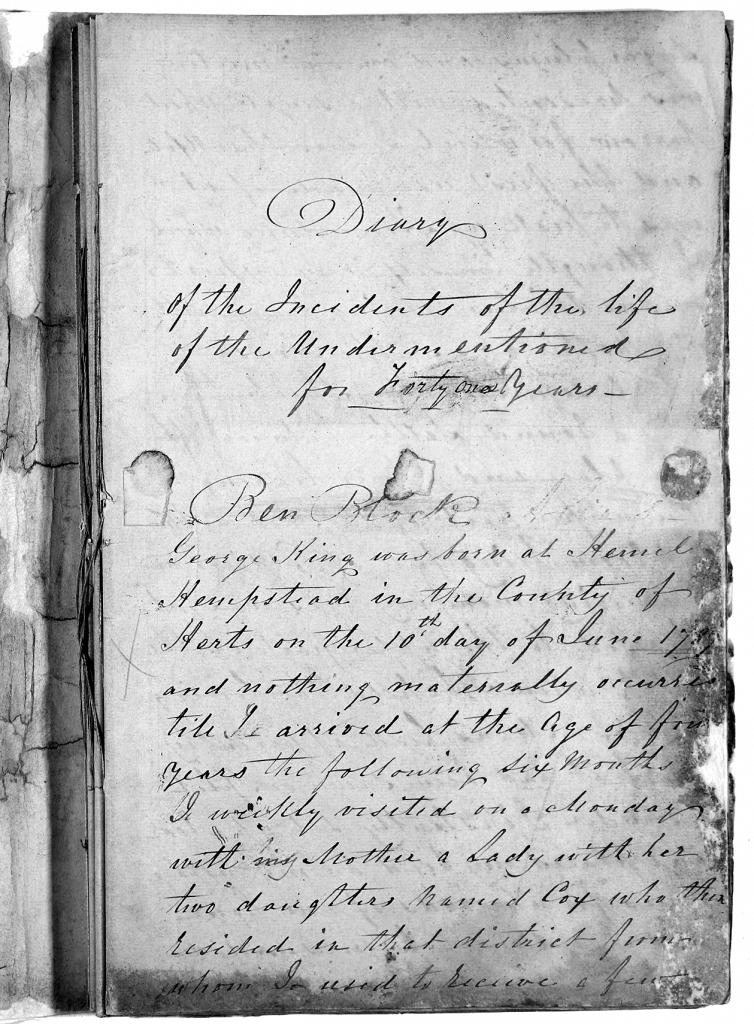

We know George King’s story because it was written by George King himself. Under the heading “Diary of the Incidents of the life of the Undermentioned for Forty one years”, the document sat gathering dust in a museum cabinet until spotted by exhibition curator Helen Berry. She saw its worth as a unique account of a child who overcame the hapless life he had been expected to lead and an opportunity to tell the story of the hospital from the point of view of its children.

George never knew his mother’s name but he would have come close to his wet nurse, Ann Yeulet, who lived in the Hertfordshire town, and who cared for the boy, at the rate of 10 shillings a month, until the time came for him to return to the hospital.

He writes of his early years that, “nothing materially occurred till I arrived at the (hospital) at age of four years… six months”. There he was subjected to a stern regime whose aim was to provide an education basic enough for the boys to pursue simple, honourable lives as labourers or serving in the armed forces.

They slept and ate communally and were smartly dressed in uniforms of Yorkshire serge picked out in red and buff, white hats with a red trim and white neckerchiefs, which had been designed by the artist William Hogarth, a governor of the hospital.

“All went on gaily,” he writes. He made good friends and took such a “liking to learning” that a sympathetic teacher recognised his diligence and he was “put to writing”, even earning on one occasion a shilling for his endeavours.

On September 25 1800, aged 13, he was sent as an apprentice to learn the art of confectionery, which he enjoyed so much that he resolved to pursue a career in the trade, only for him to fall out with his fellow workers. After a

particularly vicious fight – “a regular turn to which lasted 20 minutes” – he

fled the scene rather than face arrest, and set off to walk the 30 miles to Chatham, where he hoped to join the merchant navy.

Inevitably perhaps, he fell in with a press-gang who got him drunk and tore up his indentures. Without them he was unemployable. There was nothing for it, he was forced to sign for service on HMS Polyphemus and, in September 1804, sailed to join the fleet of Admiral Nelson, which was blockading the Spanish port of Cadiz.

What a frisson of fear and excitement the 18-year-old must have felt when, one year later on the eve of the Battle of Trafalgar on October 20, 1805, he overheard Nelson shout across to the skipper of the Polyphemus, “We shall have a warm day tomorrow.”

It was certainly that. The men stripped to their trousers because the day was so sultry and “blazed away for three hours” despite the smoke from the guns making it almost impossible to see what they were shooting at.

Life at sea was not often as dangerous as Trafalgar, but it was invariably harsh and, like any sailor, George took his pleasures when he could. He cheerfully admits going on a 14-day drinking spree: “I being so much overjoyed and Four Guineas in my pocket I took a run and did not feel

the ground under me I think a Greyhound would hardly head me.”

A melancholy invests his diary after Trafalgar. He complains of ailments such as dysentery, typhus fever and “nodes on the shin bones”, his best

friend from their time at the Foundling Hospital dies, and though he mentions casually that he has become married, the relationship does not appear to have been particularly enduring, for he is soon on his travels to the Caribbean, South America and the Mediterranean, and mentions only in passing that his wife died while he was away.

It was the “wooden world” of life at sea that drew him in 1832 to join a ship in Liverpool as a steward, sailing to Charleston, in the US state of New Carolina. George rated it a charming city and decided to stay despite being instructed by the skipper: “Don’t you go running off.”

“I left my cabin,” writes a devil-may-care George. “Put on my hat, and walked leisurely over the side.” He found an excellent guest house where he breakfasted on beefsteak, coffee and two glasses of New York whisky before buying a pair of shoes for one dollar and a quarter.

For no clear reason he set off to Augusta, 90 miles south, until he reached the small town of Walterboro, where he was given a warm welcome and offered a teaching job. He earned $50 for his work before deciding, just as serendipitously, to return to England on one of the many ships that crossed the Atlantic heavily laden with cotton grown by slaves.

Back home in April 1833, after “a tedious and wet passage”, George resolved that his seafaring days were over, only to discover that work for an old sailor was hard to come by. He tried labouring in the docks, haymaking and hop-picking, but it was too much of a struggle to survive, especially as his naval pension amounted to a paltry £16 a year and he was lonely – “lost for want of a friend” – so he applied for lodgings at Greenwich Hospital, the home for disabled and impoverished sailors.

Entry was at the whim of a ballot and, just as it had been 47 years before when his anxious mother was trying to get him a place at the Foundling

Hospital, he was chosen and given a number – 1,352.

Maybe he recognised the cold, matter-of-fact symmetry of being, once again, a number, for his diary soon comes to an end. “I was placed on the books (of the hospital) upwards of seven years since,” he writes. “And

thus ends the sequel of my story.”

What makes the words of the diary come alive are the painting and artefacts that have been gathered to trace George’s progress, such as his mother’s letter, the document that records his admission to the hospital, a Foundling uniform, the china plate, knife, fork and spoon the orphans used, and two essentials for the sailor King became: a bottle of calomel for dysentery and a half-pint copper jug for rum.

A stirring painting of Trafalgar by ED Stuart captures the tumult of the victory, while in a portrayal of life in Greenwich a pensioner wearing a

yellow coat as punishment for drunkenness stands in remorse before his fellows. A splendidly crude caricature of three sailors on shore leave with pipes, drink and a “bum boat woman” in a sedan chair capture the days when George himself was “completely stupid with the grog”.

Although he ends his own account in 1835, George was discharged from

Greenwich 13 years later when he was 63, and he seems to have found some

contentment by marrying a woman 18 years his junior and settling down in a house nearby. He was appointed clerk to Greenwich Hospital and Chapel and died aged 70 on July 31, 1857, his incredible journey ended at last.

Fighting Talk: One man’s journey from abandonment to Trafalgar at the

Foundling Museum, London, until February 27. Plus a book, Orphans of Empire: The Fate of London’s Foundlings by Helen Berry