Serene, stunning, scenic, spectacular: the superlative adjectives just keep on coming when you are cycling in some of Europe’s most beautiful places. Often too hot, occasionally too wet, but with a little preparation you too could master these memorable rides.

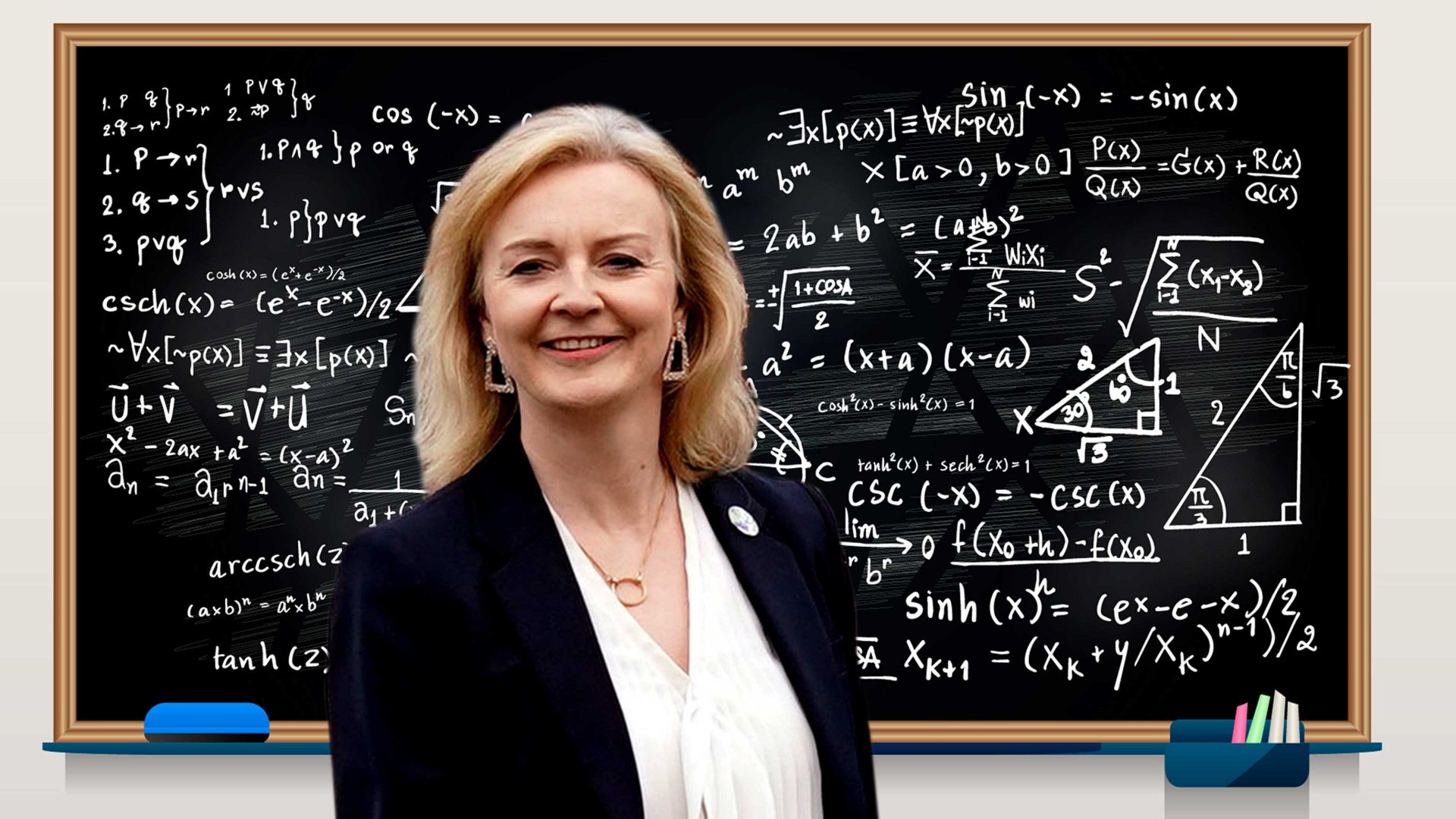

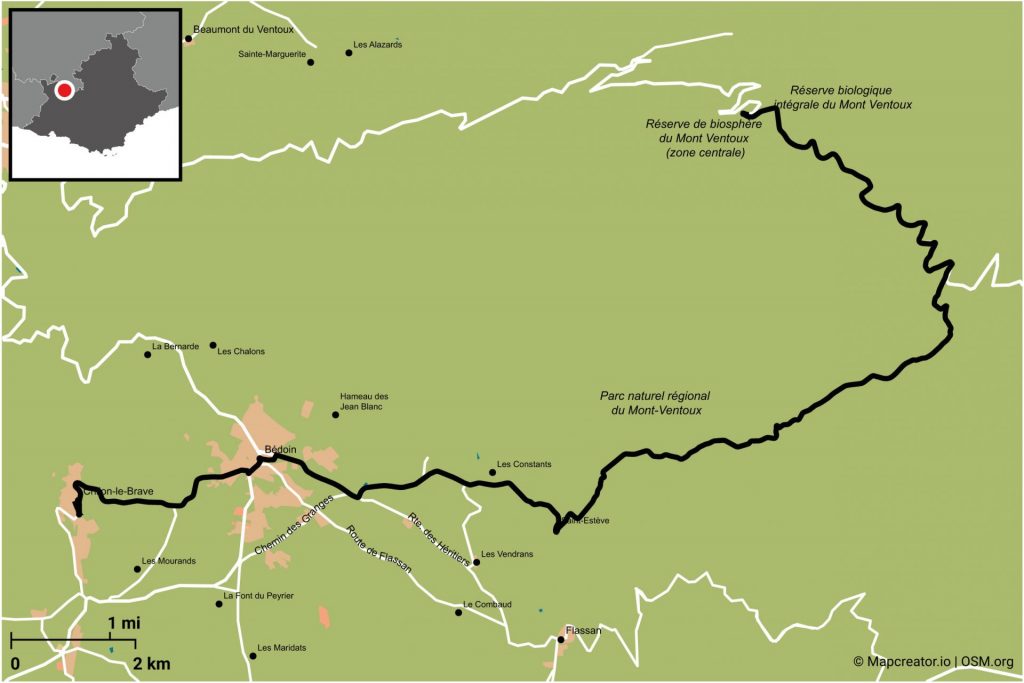

Mont Ventoux, Provence

Grown men have been reduced to tears on Mt Ventoux, one of the toughest cols in the Tour de France. My first assault in late summer 2009 ended in failure; naturally, I blamed windy weather and an unwieldy hybrid bike. Last year, on a cloudless mid-September morning, I stiffened the sinews a second time, equipped with a super-light S-Works Aethos road bike and determined to reach the pinnacle of my cycling ambitions.

An early start is key, because a 21.7km climb lies ahead and the morning sun can become relentless. Our party of three left Crillon le Brave hotel by 7.15am, racing to the town of Bédoin, before starting a slow ascent to the base of the mountain at Saint-Estève. I knew from memory that the next 30 minutes would be brutal, with gradients up to 12.6%. Squirming in the saddle, veering into the centre of the road, sucking on energy gel, I tried every ruse to banish the pain in my rear-end: flashbacks of school rugby glory, a roll-call of US presidents, in historical order. Anything to avoid the humiliation of dismounting from my bike to take a breather.

Momentum is the only way to vanquish Mt Ventoux. Every bend conquered, every kilometre passed represents a minor triumph. When the winding road eases – and it does on occasions in the forest – it is time to down another slug of water and savour the moment. Steady climbing – not mindless acceleration during the easier passages – is the most sensible course. As the two-hour mark approached, I spotted Chalet Renard, the traditional refreshment stop ahead of the final climb to the summit.

This time the winds were not gusting (they can blow up to 150km/h near the top of Mt Ventoux). But as our plucky trio ground out the metres, the temperature dropped noticeably. Suddenly, on the final stretch, I was ambushed by a couple of low-rent photographers, snapping shots and shoving a bill into my right hand. I waved them away, growling, “Thanks, but no thanks!”

With 1km to go, we passed the spot where the British Tour de France cyclist Tommy Simpson collapsed and died from exhaustion. By this time my two younger colleagues were far ahead. Still, the white-red pin of the weather station at the summit was tantalisingly close. Another 10% gradient, and then, hallelujah, the final 150m wobble upwards before heading with indescribable relief into a car park. After exactly three hours, this middle-aged man in Lycra (Mamil) had made it to the top! And I had the money shot taken to prove it.

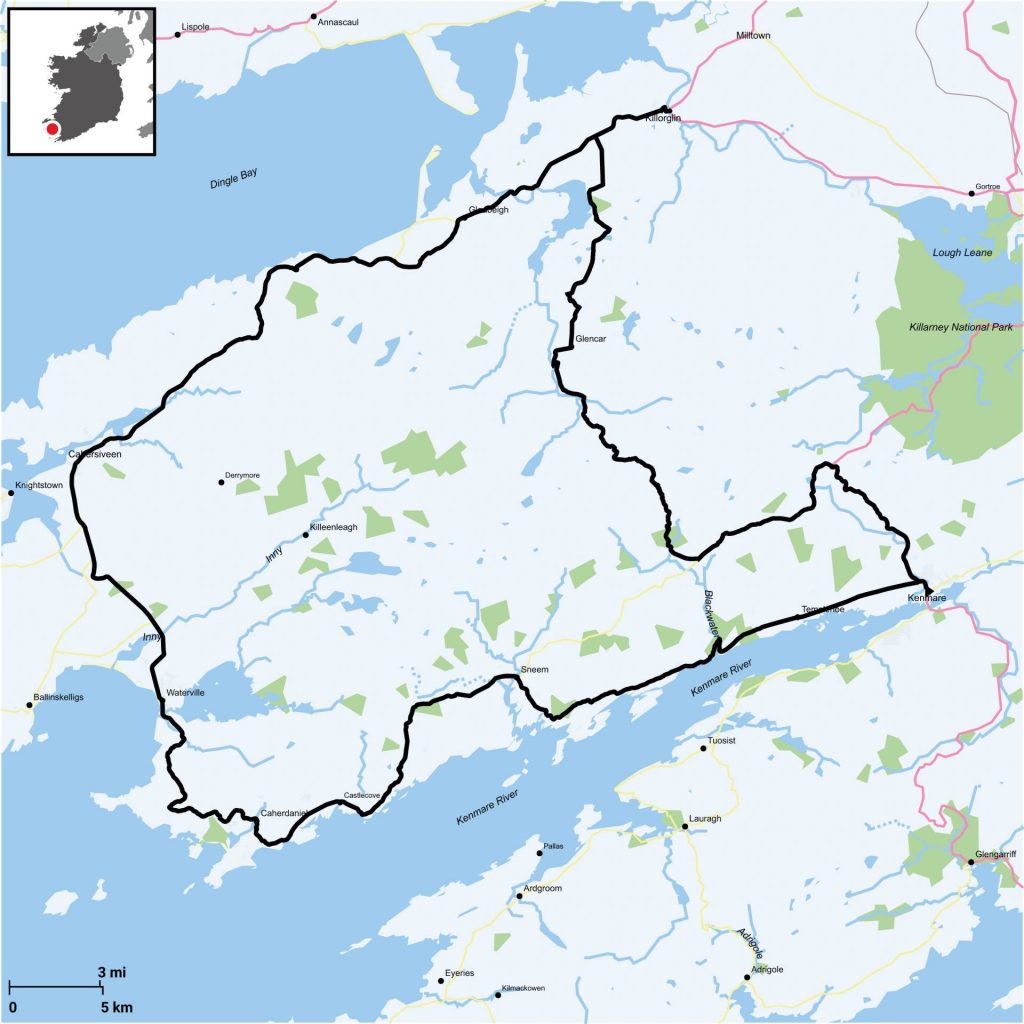

The Ring of Kerry, Ireland

Come to Ireland, my New York friends said. There are few more serene places to bike in the world. Having spent three uplifting trips with the same group in Provence, Tuscany and Umbria, my wife and I asked ourselves: what could possibly go wrong?

The answer is everything. For starters, the weather. Every day at 8.45am our party of 12 assembled after breakfast at the Park Hotel in Kenmare. At 8.46am, the drizzle would start. By 8.48am the drizzle would turn into a shower. By 9am, the heavens would open. By 10am we were all in the pub, shivering over steaming tea.

On most days heavy mist descended, leaving the magnificent Irish coast around Dingle and Kenmare Bay largely invisible. Victoria and I had experienced cloud bursts on an earlier, highly enjoyable road trip to Connemara and Donegal; but the area around the Ring of Kerry, including the aptly named Waterville, was regularly enveloped in a weather disaster of biblical proportions.

Back in 2011, there were none of the fancy digital gadgets that these days automatically guide the riders along routes north, south, east and west.

We had to make do with printed instructions stuffed into plastic waterproof folios attached to the bike handlebars. The moment we took the paper out to check our location, the rain reduced the instructions to a sea of ink.

On one ascent to Ballaghbeama Pass, Victoria and I could barely see

anything beyond 20m, so fierce was the hail. On the (fortunately mild) descent, we both experienced something close to aquaplaning, our bikes sailing through the air before landing in giant puddles and shuddering to a halt. It was half funny, half ludicrous.

That same day, one member of the group appointed themselves health and safety inspector and ordered us to stop pedalling forthwith and retire to the minibus back to Kenmare. I was tempted to repurpose the “cheese-eating surrender monkey” jibe levelled against the French in Gulf War II, but common sense prevailed.

Still, there is nothing to beat Irish hospitality. Every night our hosts would take sodden shirts, socks and bibs, stick them in the dryer and lay them out in the morning, neatly folded, for collection. And let’s not forget the Irish whiskey, the best antidote to rain and cold devised by man.

Mallorca

If you like long, slow climbs followed by long descents at speed, Mallorca is the place. The road surfaces are smooth (gracias, Brussels) and the mountain scenery majestic.

I have ridden in spring and early autumn in Mallorca, and on both occasions the experience was entirely positive. But water bottles are essential: anytime between April and October, temperatures can rise to 30C. Best preparation is to do a few days of hill-climbing beforehand. Turning up on the island with no pre-training is likely to result in sore back and calf muscles over the first two days.

Sir Bradley Wiggins trained in Mallorca ahead of his 2012 Tour de France victory. One of his favourite testing grounds was the Sa Calobra climb, Mallorca’s most famous, spectacular and, arguably, toughest ascent. It’s around 9.5km, with an elevation of almost 600m, followed by endless hairpins snaking down to the sea.

Those descents make for a heart-pounding ride, best managed by judicious use of brakes rather than extravagant tilts to left and right. Remember: you are riding a road bike, not a TT motorcycle! Once back at sea-level, there are some spectacular rides along flat coastal road, such as the route via Banyalbufar. An added advantage: the cars are biker-friendly and give everyone a decent berth.

The ride from Port de Pollença to the famed Cap de Formentor lighthouse is one of Mallorca’s highlights. The distance is around 35km but it includes 1,000m of climbing, through thick pine tree forest interspersed with breathtaking views of the sea below. Take a couple of moments at Mirador

de la Creueta for snapshots, and then brace for the final ascent along switchbacks to the top for a wonderful panoramic view of the peninsula.

With its plunging ravines and steep roadside drops, Mallorca is not for the faint-hearted. But the quality of the roads, the signage and the friendliness of locals make it a go-to destination for the serious cyclist and hardy amateurs like me.

Final tip: Mallorca has plenty of mountain tunnels. Do not forget to take off your sunglasses or risk serious disorientation.

Sicily

Ten months after breaking my collar bone on a gentle ride in the Surrey hills (my front wheel skidded on wet leaves), I was ready to climb back into the saddle.

The location was Verdura, Sicily, the spot chosen by Google to host its inaugural summer conference in 2014 known as “The Camp”, a three-day gathering of movers, shakers, sports celebrities, scientists and innovators. Several of these alpha males and females were keen cyclists, with tanned faces and toned calves that left me feeling slightly intimidated as I stood in line for my water bottle.

The early afternoon sun was blazing down as we navigated our way out of the five-star Forte Hotel to the main highway. Several members of the women’s Italian national team were riding in the group – what we call in economics “a leading indicator”. With no pre-training, no knowledge of the terrain and no proper protection against the sun, I began to sense that I was on the road to perdition.

After 40 minutes, the perspiration was dripping down from my forehead, congealing the sun cream I had casually smeared around my eyes. Lesson number one for riding in heat: wear a bandana and take the time to apply sunscreen properly to prevent eye irritation.

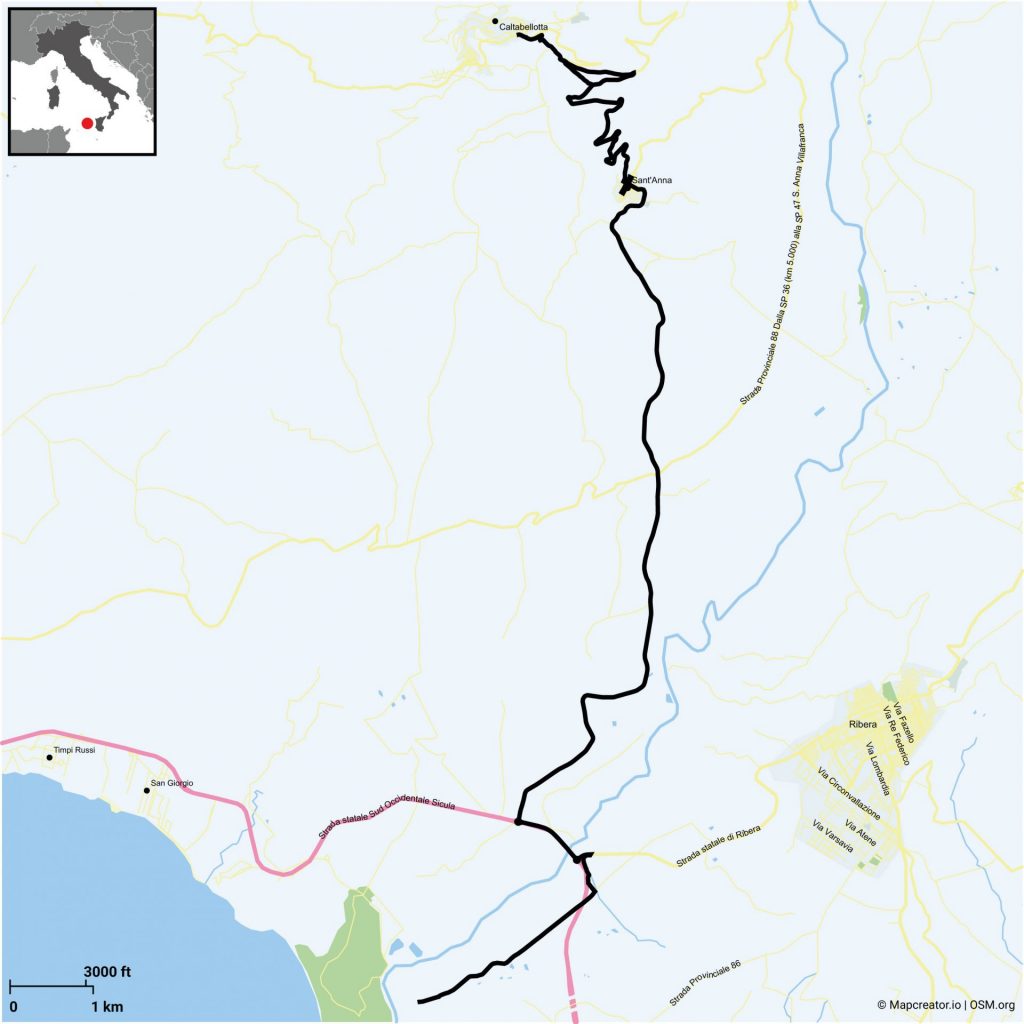

By 90 minutes, I had slipped to the back of the group, pedalling valiantly against the 4% gradient. As the long ascent to the town of Caltabellotta

grew steeper, my head began to bang, a familiar warning that sun-stroke is not far away.

Once again, I poured a pint of water over my helmet to cool down, only to be hounded by a stray dog whom I assumed, in my delirious state, must have had rabies. How long to go, I asked. Just another couple of kilometres, came the (inaccurate) reply.

When I finally arrived at Caltabellotta, which literally hangs off the top of the mountain, I was ready to explode. I hated coming in last, but my hubris had come at a high price. Then everything changed. The descent was indeed

thrilling, with nine switchbacks on a road called the Strada Provinciale from Caltabellotta to Sant’Anna, and then along the highway back to Verdura.

Over the next five years at the Camp, we completed several other memorable rides, often stopping off at the famous ceramic museum at Burgio, with a tremendous view of the valley below.

Another top tip: the descent from Lucca Sicula back to Calamonaci is around 20km, a breathtaking ride that (almost) erased the pain of my wobbly comeback in 2014.

Veneto

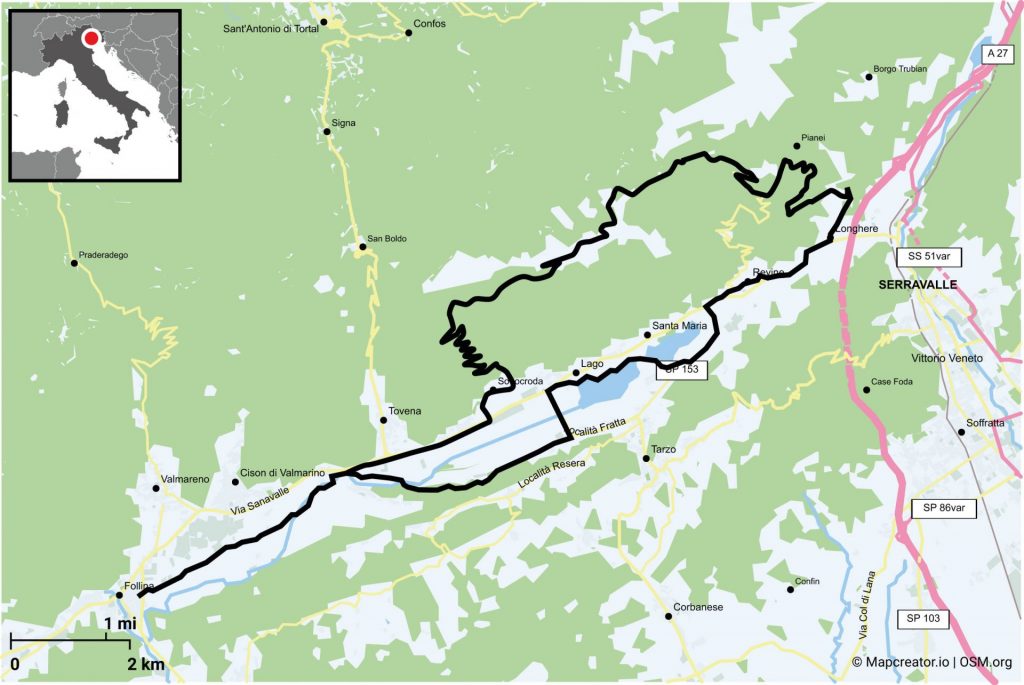

One hour’s drive north of Venice lies the region known as “prosecco country”, a well-kept secret among cycling aficionados. Our base was in

Follina, a beautiful market town with boutique hotels and culinary delights

such as taleggio cheese, bigoli pasta, polenta and porcini followed by 100 flavours of sorbet ice cream, all washed down with light, tasty wines.

The Veneto cuisine is the essential counterpoint to cycling in the region, a mixture of mildly testing and outright exhilarating. Veneto has little of the

ruggedness of the Pyrenees; and the lush topography is a world away from

the steepling parched hill-mountains of Mallorca. But the ascents in Veneto

will get the heart beating a little faster. The roads begin slowly, before the gradient starts to increase. Nothing more than 6% or 7% but definitely enough to whet the pre-lunch appetite.

What lifts the spirits are the descents, often turning into 20-minute joy rides taking in spectacular scenery below: Palladian mansions perched above the roadside; market towns like Asolo, known as the Pearl of the Province of Treviso or simply “the City of a Hundred Horizons”. The town’s mountain setting, looking over the deep green valley below, remains etched in the memory, alongside our delightful base at the Villa Abbazia Hotel in Follina.

A personal highlight was to be digitally recorded in order to establish my riding posture and thereby the perfect position for the handlebars, seat

and pedals of my new bike. Having been wired up, I was instructed by an expert to pedal at varying speeds. All data having been digested, the necessary adjustments were made. Perfetto!

On Sunday morning, ahead of a final night in Venice, we were asked to do a

Covid test. The country doctor, not best pleased at having his weekend disturbed, inserted the swab in my left and right nostril and applied it with

the rigour of a chimney sweep. Negative, he later sniffed.

Which most definitely did not apply to our trip: it tested positive in every sense!