In the summer of 2016, I interviewed Louis Stettner at his home in Paris. The photographer, who died just a few months later, aged 93, was perhaps the last of the American 20th-century cultural figures to have made the French capital their home. A comprehensive new book, Louis Stettner, and an accompanying retrospective exhibition at Fundación MAPFRE in Barcelona, now surveys his transatlantic shutterbug story.

Stettner’s philosophical approach to photography was rather like that of the Bard. “Shakespeare gets people interested in his material, but embedded in the material is the poetry,” he said. “They’re forced to get the poetry, you see, because the structure is something that they feel at ease with and want. The same with photography. It’s a doorway to getting poetry.”

He stood in that doorway for three-quarters of a century. Stettner began taking pictures during the Depression, was a combat photographer in the second world war, befriended masters such as Paul Strand and Brassaï and shot for Life and Time magazines. He found his muse on the New York subways and Parisian boulevards during the 1950s, producing works that captured metropolitans – et les métropolitains – at work, rest and play.

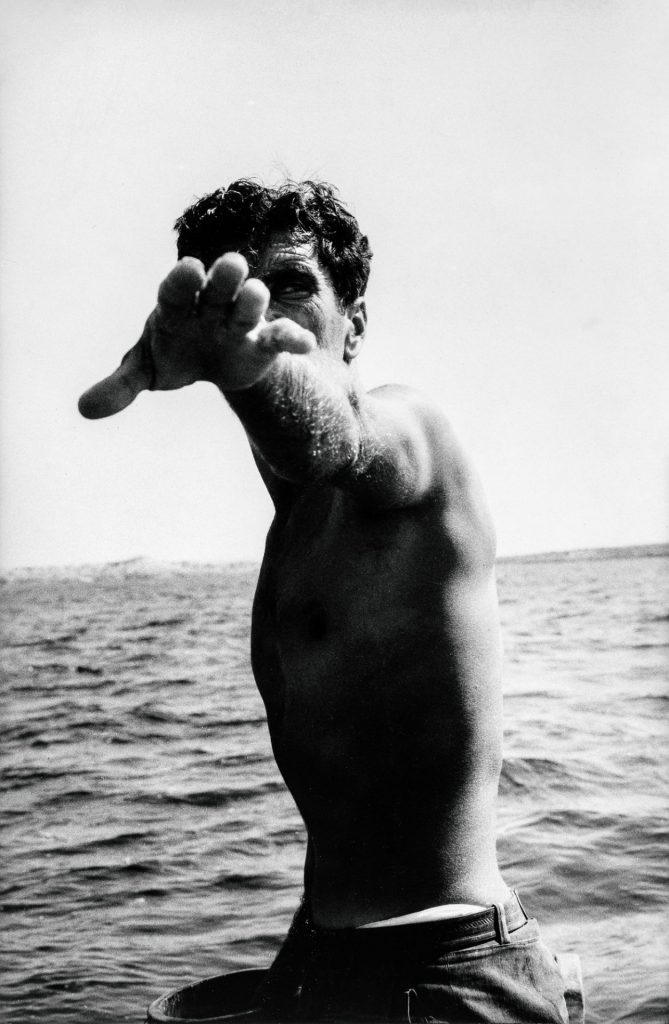

Pepe & Tony, Spanish Fishermen, Ibiza, Spain, 1956

Sitting in the kitchen of his home in Saint-Ouen, on the industrial fringes of Paris, Stettner was engaging company, a humanist with a fisherman’s beard and a robust laugh. His ability to find grace in urban settings was celebrated in a major retrospective at the Centre Pompidou shortly before his death, recognition that surprised him. The irony, he noted, was that half a century earlier no one considered photography “capable of saying something profound”.

He was born in 1922, into a family of Austrian émigrés in Brooklyn, and became interested in photography as a teenager. “Someone wanted to sell an old wooden camera on a tripod. I gave a week’s salary and bought it,” he recalled. “I was naive.” One of his first shots was a picture of the tree in his backyard.

At 18, he volunteered to be an army photographer and was sent to the Philippines. “If you went out to the frontlines everyone spent a good deal of time being invisible. So, I took pictures of whatever I could,” he said. “Afterwards, I was sent to take pictures of Hiroshima.”

He visited Paris for the first time in the mid-1940s and subsequently split his time between Europe and America, working as a photojournalist and teacher. “You could go off with a suitcase and a camera and hire yourself out as a freelance. There were lots of magazines. Everyone needed a photographer.”

Meanwhile, he worked on his own projects. “People were very respectful. If I went out, I wore a tie and no one ever said ‘don’t take my picture’.”

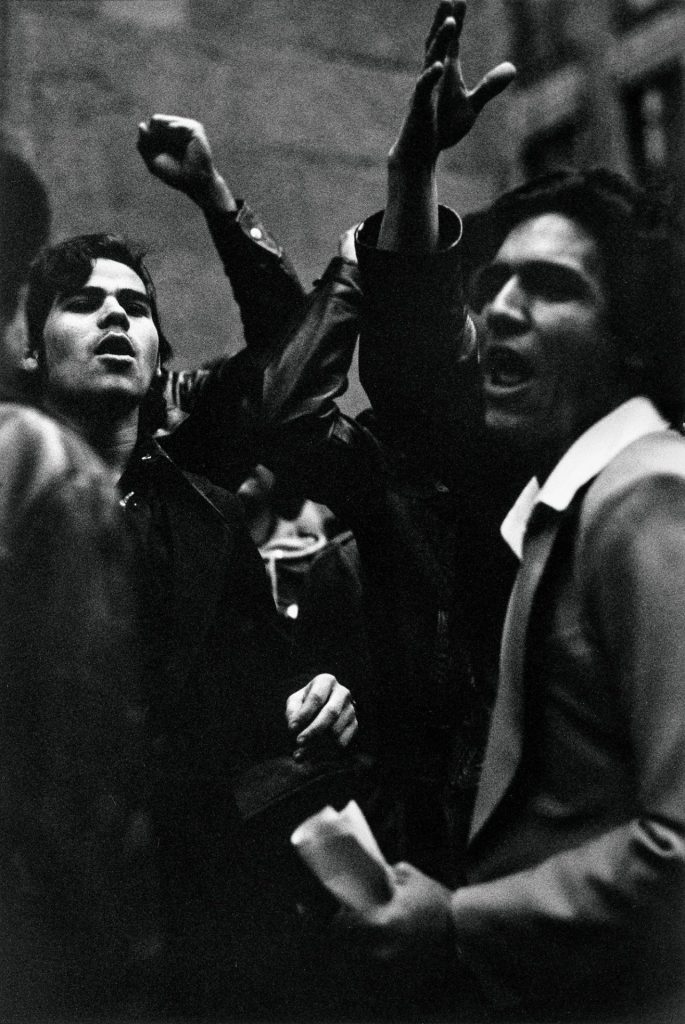

In New York, he joined the Photo League, a left-leaning cooperative of photographers that fell to McCarthyism in 1951. At the time Stettner was employed on the Marshall Plan to take pictures for the government. “One day somebody called me, FBI or CIA,” he recalled. But Stettner refused to cooperate. “I was fired. It was a very bad period.”

With the passage of time, many of his best-known shots of New York became elegiac. His 1979 photograph of a gull flying in front of the World Trade Center is particularly poignant. His most famous American series, taken in 1958, captured the hazy bustle of the original Penn Station – a cathedral of ornate girders and fine masonry – just five years before it fell to the wrecking ball.

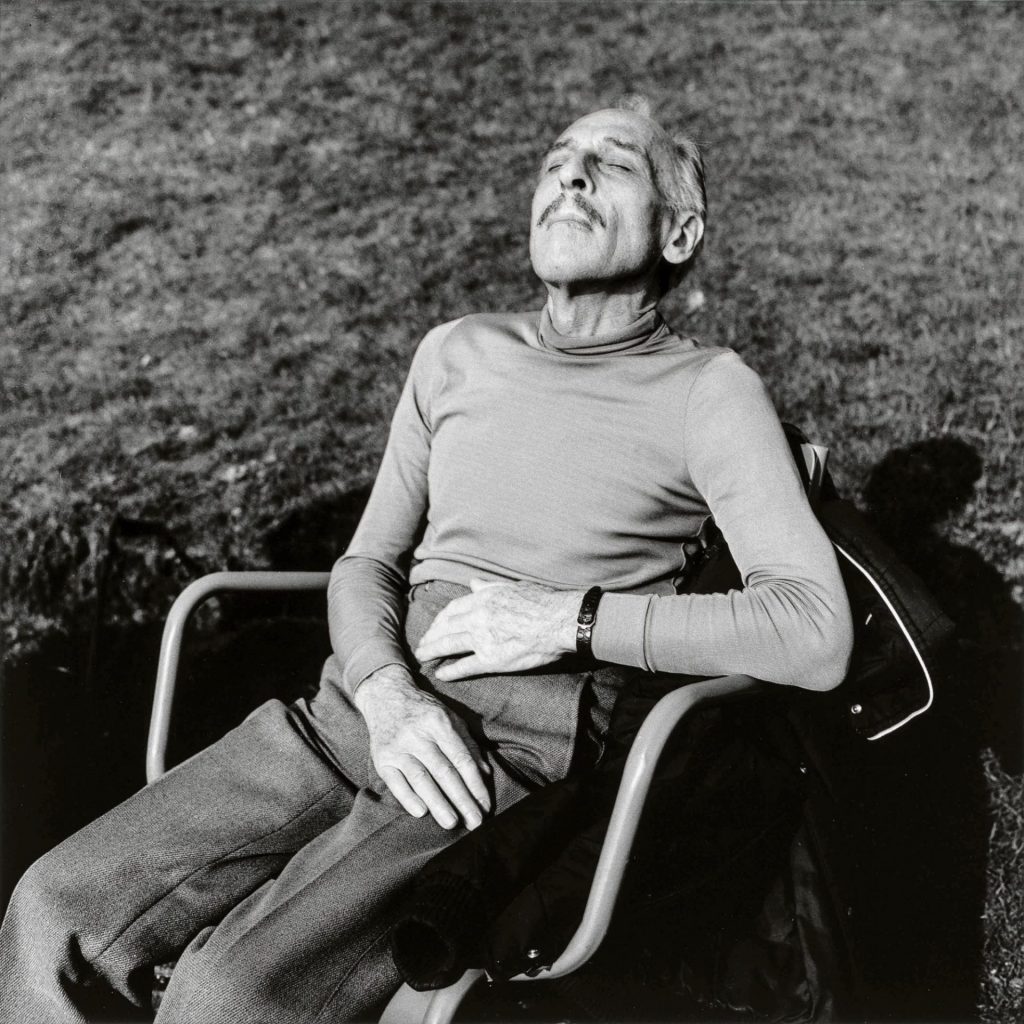

His pictures of passengers in repose – reading, playing cards, smoking and snoozing – speak of stillness in the city. “I think people then were much more capable of entertaining themselves,” he told me. “Or renewing themselves through periods of not doing anything, which is a lost art now.”

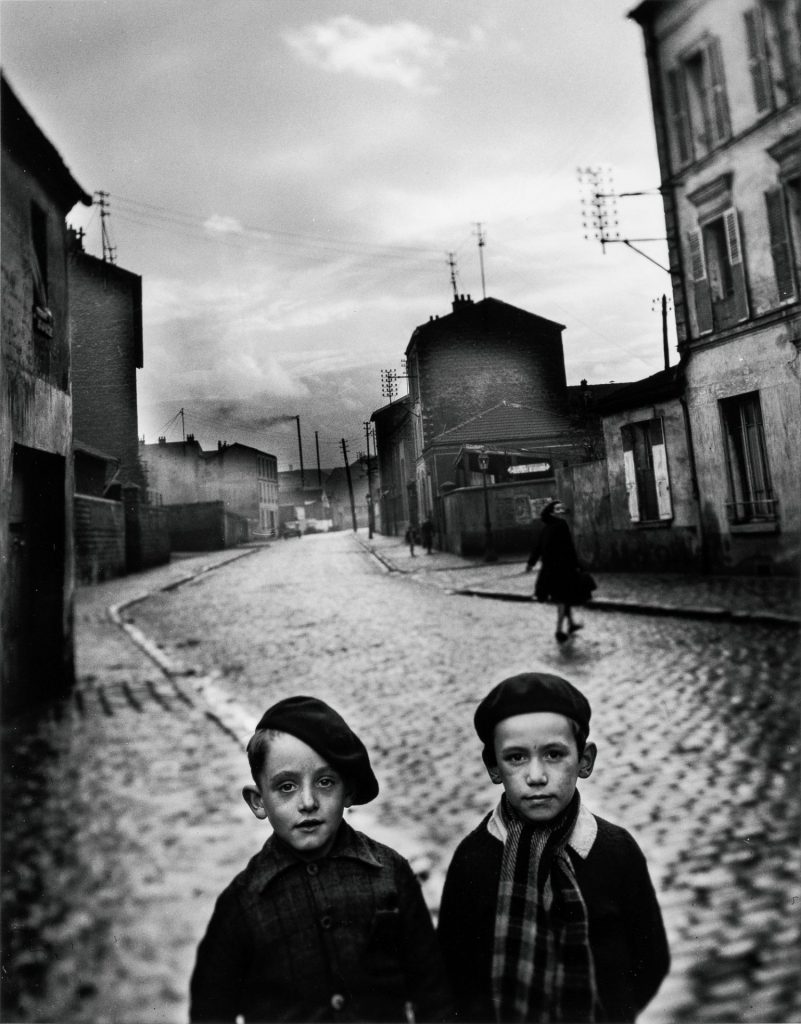

In postwar Paris, he photographed the melancholy cafe characters and watchful concierges, the newsstands and skewed lines of the bridges over the Seine. He found that his adoptive city had different virtues from his home town. “The attraction of Paris is beauty,” he explained. In New York, the streets were paved with kinks and uncertainties, while in Paris elegance reigned.

In 1956, he accompanied two Spanish fishermen – Pepe and Tony – trawling off the coast of Ibiza, shooting closely cropped near-abstract portraits of the pair working their nets. Other European subjects included Dutch farmers – in a time when they still wore clogs in the fields – Portuguese boys playing on the beaches and chic sunbathers lounging on the Côte d’Azur.

He carried on working until the end of his life, producing a late pastoral series in the ancient woodlands of the Alpes-Maritimes, monumental landscapes of gnarly cork oaks and olive trees taken with an 8×10 view camera. “With a big camera you can be more meditative,” he observed. “Because you are looking at things upside down. You have time to think.” Poetic indeed.

Louis Stettner is published by Thames & Hudson