Tacked untidily to a sheet of plywood on a hospital wall, a series of sketches demonstrate how workers should deal with a nuclear contamination; wash hands, shower, boil water, disinfect, scrub the walls and the stairwells down.

The notice probably wasn’t given a second glance until April 27, 1986, when the residents of Pripyat, a small town near the Ukrainian border with Belarus, were startled from their daily routines by orders shouted from loudspeakers mounted on military vehicles.

“Attention, attention: trust me comrades, the Communist Council of Deputies informs you that following an accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the city of Pripyat, the amount of radiation in the air has risen above normal.”

Emergency measures had been taken, promised these stentorian voices. People needed to evacuate.

It was a lie. No measures had been taken. The blustering broadcast was an attempt to disguise the fact that Reactor 4 of the Chernobyl nuclear plant had exploded, spreading contamination 200 times greater than the atomic bomb at Hiroshima. Around 65 million people would be afflicted with radiation poisoning.

Few suffered more calamitously than the 50,000 inhabitants of Pripyat, whose evacuation was delayed for 36 hours after the accident.

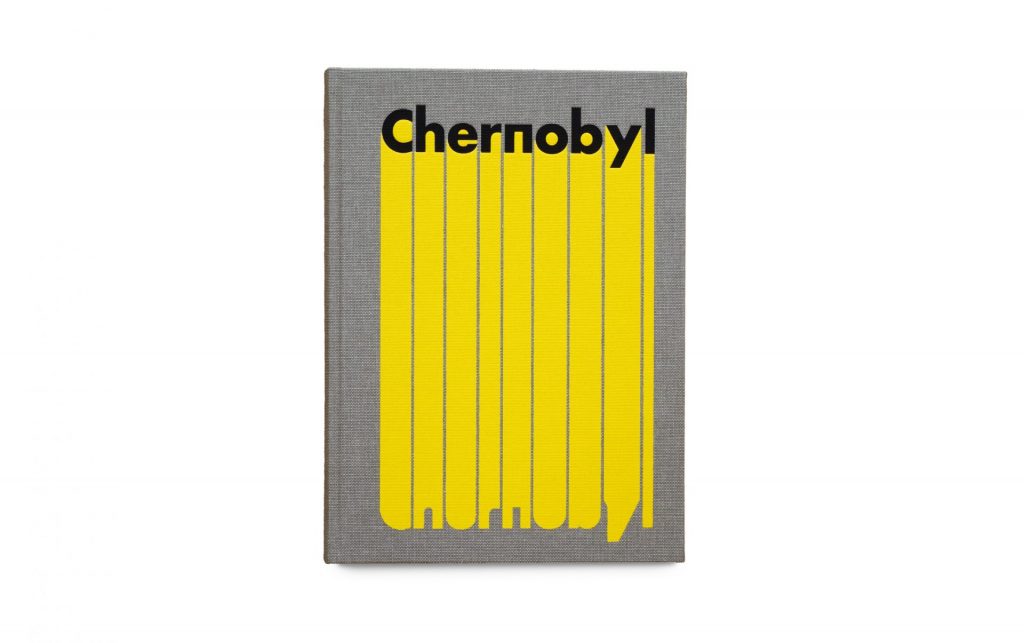

The effect of the blast and its terrible legacy is powerfully documented in Chernobyl, a collection of images by the Italian photographer Pierpaolo Mittica.

His pictures, taken between 2002 and 2019, document what has become a monstrous scrapyard, with rusting cranes, farm machinery abandoned in forests, sunken ships half in, half out of the River Pripyat. There are gloomy panoramas of derelict blocks of flats overshadowed by the huge curve of the protective cover built to prevent further radiation leaks. Empty houses and lonely streets, made all the more desolate by a dusting of snow and a statue of Vladimir Lenin, after whom the deadly reactor was named, are now distinctly mildewed.

If one had to imagine the end of the world, this is it. But to Mittica’s surprise, he found that within the 30km exclusion zone placed around the plant, people had continued to live and work – including the 2,000 or so still employed to keep the reactors safe – and, even more unexpectedly, he discovered that some used it as an adventure playground and others as a place of pilgrimage.

Bizarrely, Chernobyl had become a tourist attraction for 60,000 curious sightseers every year. Mittica joined a tour, photographing them as they took selfies on the roofs of empty buildings, standing precariously with the reactor in the background, one posing with a cow’s skull over his head. They bought T-shirts and mementoes from a small mobile tourist office, incongruously flanked by two life-sized figures in masks and protective gear.

Now with war raging, what Mittica disapprovingly labels “dark tourism” has come to an end, not least because the entire region is heavily mined, leaving the place ossified in time – a “new Pompeii” as Yuriy Tatarchuk, the manager of the Chernobyl tourist information centre, proudly dubbed it.

That’s not such an exaggerated claim. Just as visitors to Pompeii are witness to scenes of dance and domesticity from two centuries ago, Chernobyl will one day be seen in much the same way.

In what he calls “an open air museum of Soviet history”, Mittica photographed a ferris wheel, now surrounded by undergrowth and trees. It was supposed to be opened for the first time on May 1, 1986, for the bank holiday celebrations, but never turned. He found children’s play cabins decorated with cartoon figures of a rabbit, a fox and a pair of bears. No one will play in them again.

He entirely captures the sense of abandonment with a solitary figure in a deserted bus station, a clutch of lone individuals in an inhospitable staff canteen, the empty theatre, its roof held up by a makeshift wooden frame, the floor in a state of disintegration, the stage still sporting a framed poster of the Soviet hammer and sickle alongside a photograph of a stolid, official-looking fellow. Perhaps the theatre director.

In the huge, dusty interior of a hangar close to reactors number 5 and 6, the figure of a worker whose job it was to clean radioactive particles from the scrap metal is almost lost to view amid the heaps of rusting material.

It’s an image that emphasises the colossal scale of the ruined buildings, but the smaller, intimate images such as the faded health and safety notice have as much impact, maybe more.

It’s hard to imagine why anyone would want to live in such a benighted region, but one group of residents who were resettled in large cities like Kyiv decided that their bond with the land and their long-established way of life was too strong. About 1,200 of them defied the Russian ban on living there and ignored the threat of radiation. They went home.

Known as the samosely, or resettlers, they are old and set in their ways, living in what outsiders would consider fearsome poverty, in rooms with cracked walls and peeling paint, shabby wall hangings, piles of clothes and crumpled sheets. A table laid with the simplest of fare – bread and borscht, a stained tin mug alongside an opened jam jar and a mouldy loaf of bread – suggests that tea is about to be served. A washing-up rack piled high with unwashed crockery and, oddly, two cheese graters and a roll of toilet paper all show how lived-in this decrepit building has become.

Invariably a picture of the Virgin Mary hangs on the wall, alongside sepia pictures of these people as young couples.

We see only the gnarled hands of 83-year-old Hanna as she trims her mushrooms, but now, not only is her food and water contaminated, it is dangerous to pick mushrooms in the forest because of the mines.

These doughty folk have defied the rules, but one group may never again be able to visit what to them is a sacred place of pilgrimage.

Chernobyl is home to a major branch of the Jewish Hasidic movement, which was founded there in 1730, only to endure centuries of persecution, culminating in virtual extinction by the Nazis.

One group escaped to the US in the 1920s, but never forgot their heritage. Every year until Covid struck they would make a pilgrimage to the cemetery, where they would lie and pray at the one remaining synagogue. These are sombre figures in their dark coats and hats, almost merging into the shadows of the building as they pay their respects at the tomb of the movement’s 18th-century founder.

If they are driven by faith, a band of young men who called themselves Stalkers were driven by adventure. They ignored the perils of contamination to trek across the zone for 60km, mostly by night to avoid police patrols, camping in deserted houses, living off canned food and drinking the water – contaminated or not. They were fans of the videogame S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl, which was inspired both by the events at Chernobyl and by a film, Stalker, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1979.Mittica sees them as a kind of “post-romantic traveller, in love with places they consider almost sacred and imbued with a tragic history they have heard about all their lives”.

But his pictures reveal the dirt and discomfort the Stalkers, in their military-style fatigues and beanies, endured (or maybe enjoyed) in the name of adventure. In the photos they appear to relish the squalid rooms and grubby mattresses, clothes piled high or left on the floor, where they gather to eat cans of food heated on a camping stove. But it’s all worthwhile when they reach Pripyat, as the joyful pirouette of a Stalker on the roof of a building proves. Mission accomplished – though it is salutary to realise that those daring, “romantic” young men may today be fighting a war.

Mittica has not only recorded the physical evidence of that fateful day when the power plant exploded. In the village of Radinka, only 300 metres from the exclusion zone, he met families who have not been able to leave the area because they cannot find anywhere else to live or work.

The scenes seem so everyday. Schoolgirls hanging out in a corridor on their phones, a teaching assistant preparing a school meal, a teacher with a well-behaved class.

He spent time with two brothers, Igor and Vladkin, as they larked about and posed self-consciously in front of a forest scene tinted an improbable blue.

All very normal. But 9 million people in Belarus, Ukraine and western Russia still live in areas like Radinka, where they are afflicted with levels of radioactivity so high that they have caused a 100-fold increase in the incidence of thyroid cancer and a 50-fold increase in cancers such as leukaemia, bone and brain tumours.

As well as Igor and Vladkin, Mittica found children for whom life is far from normal. One of them was six-year-old Amnia, who was confined to bed suffering from osteosarcoma, a malignant bone tumour. Another was Anna, six months old, pictured just before she had surgery for hydrocephalus, which is caused by radioactive particles in the foetus. Ania, a 23-year-old mother, gazes hopelessly into the middle distance while holding her baby, Roma, also stricken with hydrocephalus.

They are all the second-generation victims of the blast, all likely to die before their time. These poignant photographs reveal the true legacy of the Vladimir Lenin Nuclear Power Plant.

Chernobyl by Pierpaolo Mittica is published by Gost Books