In 1938, 14-year-old Lisetta Carmi and her Jewish family fled Italy’s fascist regime for asylum in Switzerland. She recalled how they escaped on foot, she helping her mother with one hand and with the other carrying sheets of music.

After the war they returned to Italy where she trained as a professional pianist. By 1960 she was an international success. That obviously was to be her career.

Not so. That same year, moved by the plight of the Genoese dock workers who were striking against the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement, Carmi marched by their side in protest. Her teacher warned that she risked having her hands damaged if violence broke out. “I didn’t care about that,” she recalled. “If my hands were more important than the rest of humanity, I would have stopped playing.”

That bold, quixotic decision was typical of the woman, who died last year aged 98. Soon after she went to Puglia where she took a cheap camera and nine rolls of film and photographed Jewish catacombs – “beautiful and fascinating places.” Friends were so impressed that they compared her to the French master Cartier-Bresson.

“I had never taken a photograph before in my life,” she recalled, though years later she explained how she had come from a family of amateur photographers who had “silently infused” in her the desire to understand the world through images.

She stopped the piano and took up photography. The results are on show in Lisetta Carmi: Identities, at London’s Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art.

In a rare interview, she explained what motivated her: “My passion for my fellow human beings has brought me to witness extreme situations in a world that is unjust yet fascinating at the same time. A world that I didn’t always understand, so I photographed to understand life.”

That quest took her around the world observing the oppressed and the marginalised. She visited Israel, Palestine, the anarchist Provo movement of Amsterdam; she was moved by children in Venezuela foraging for food on rubbish tips. But perhaps most powerful of all are her images from Genoa.

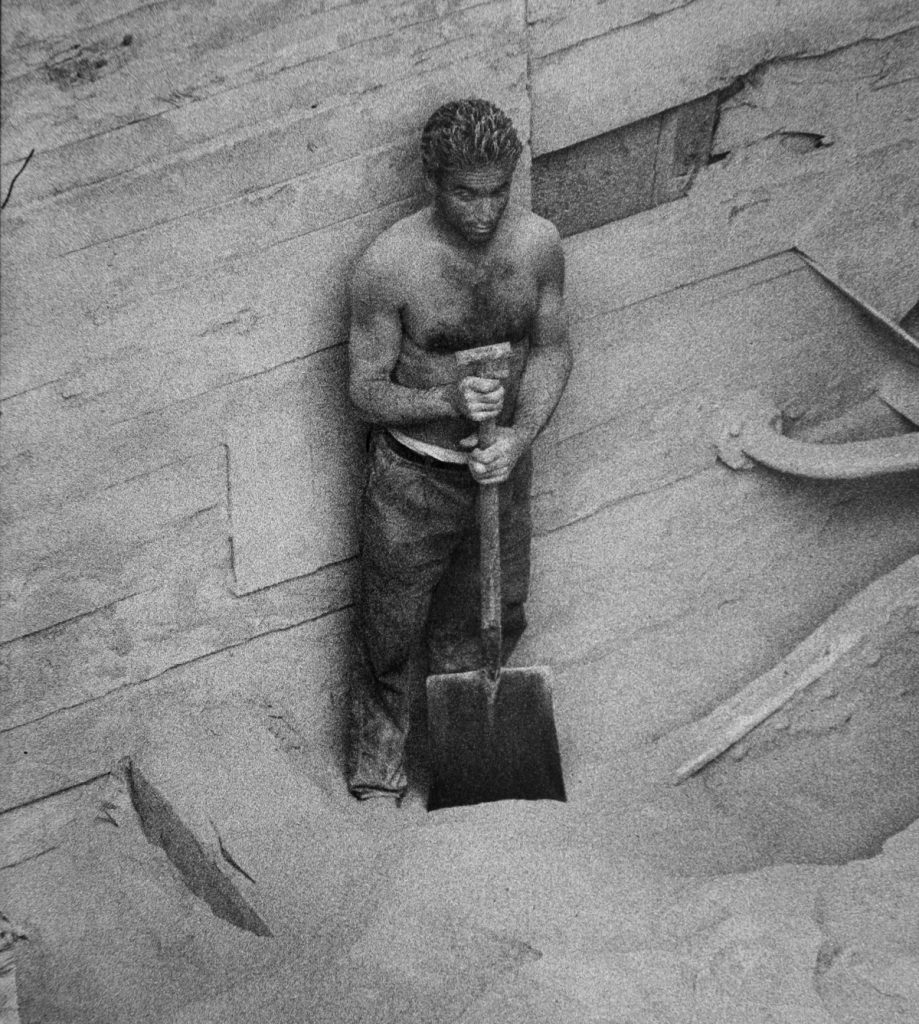

The docks were crucial to the character and economy of the city, and in 1964 she persuaded a cousin to smuggle her into the docks where the men unloaded cargoes of phosphate. At the time, no women were allowed.

Phosphate could cause heart and kidney failure and osteoporosis, eventually death, yet the men had no protection. Some even used rags for shoes, as they worked deep in the holds, filling sacks with the fertiliser and loading them onto the dockside.

In other images huge grabbers lift cargoes from holds, while cranes and gaunt scaffolding, black against the sky, dwarf the men. There are rope hawsers as thick as a man’s arm and a universe of steel, iron and billowing steam.

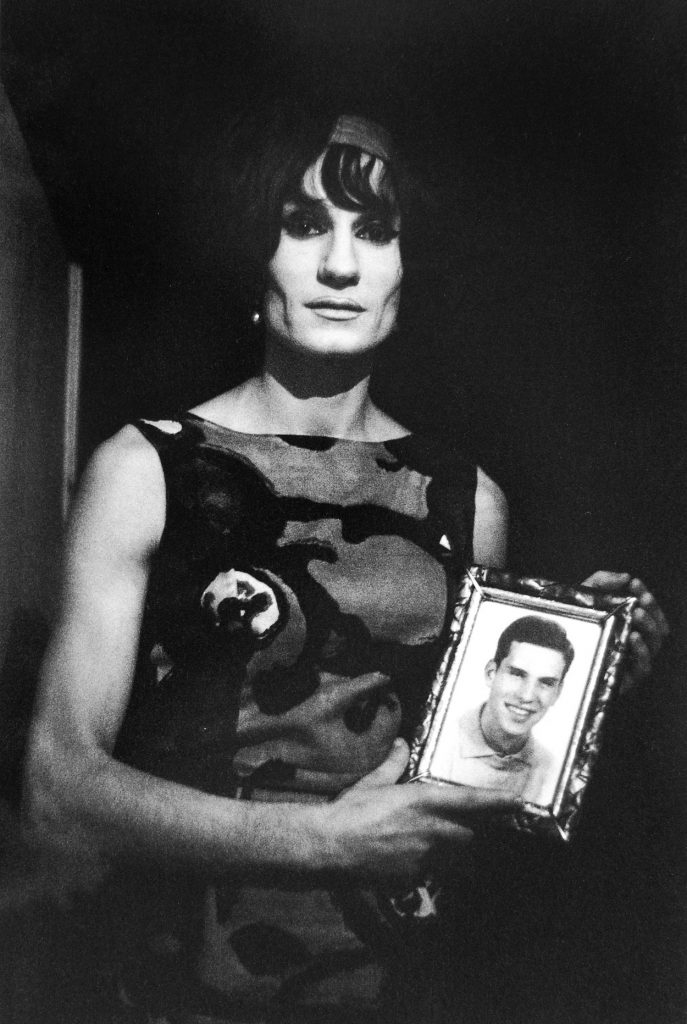

Carmi first came across what today we would label as the LGBTQ community at a party on New Year’s Eve 1965 and, having convinced them that she would not exploit them or use their pictures to shock or titillate, she spent six years capturing their covert lives.

Carmi was to be abused as a “dirty girl” for the project. After all, not only were i travestiti invariably sex workers who frequented the narrow, grubby alleys of what had once been the city’s Jewish Ghetto, gender identity was a taboo subject in Catholic Italian society and cross-dressing was illegal. As she wrote in 1972: “It takes courage to do what they do, and to face the often dramatic and violent consequences. Many of them have no alternative for employment: as men, they look too feminine, and as women, they run into the obstacle of being listed as male on their ID. They must deal with incredible loneliness, because society both seeks them out and isolates them, forcing them to live in what are basically ghettos.”

One of her subjects, known as Dalida, glamorous in immaculate makeup and a chic dress, holds up a picture of himself as a male in acknowledgement of another identity. Cabira, sprawls seductively across a bed, in a blonde wig, while the exotically named La Bella Elena appears in an auburn wig and a natty suede jacket and also poses naked. He, in fact, was one of the few to find work in the docks.

What stands out, however, is the very ordinariness of their surroundings. Their rooms are papered in faded floral prints, a Bronzino portrait of a child hangs on one wall, a clutch of chintzy china cherubs sit on a sideboard next to a novelty phone, a sentimental picture of a mother and child looks down on a couple larking around on a bed.

Those endearing, positively homely, touches emphasise the mismatch between the spirited attitudes they strike and the shabby rooms and grimy streets they inhabit. Some of i travestiti are exotic, all are defiant, but look at the eyes; however dispassionate Carmi’s photographs, what we see is that these are all sad, solitary, people.

“These transvestites helped me understand that we all have the right to decide who we are,” she said. “When I was little, I would look at my brothers and long to be a boy like them. I knew I would never marry, and couldn’t accept the role that was expected of women.”

It was yet another role which took her in an entirely different direction in 1978. As abruptly and decisively as her previous transformations, she decided to establish an ashram in her home in Puglia on the urging of a spiritual leader who had inspired her in India. She never picked up a camera again.

Fortunately, a video of an interview with Carmi at the Estorick fills in the many gaps in her life and work, including an extraordinary series of photographs of the ageing poet Ezra Pound. Shamed for his support of Mussolini and Hitler and his violent antisemitism, he had taken refuge in a village in Liguria, north Italy.

It was 1966, Carmi and a journalist knocked at the door of his small home and Pound peered out. He did not speak but Carmi snapped away. “He seems to me like an apparition,” she recalled, “I am almost afraid that the strength lying within him might be unleashed, the terrible strength and lost desperation that shine in his eyes. We have encountered the shadow of a poet… I captured his pain of living.”

It was that intensity, that quest to tell the truth about the oppressed and the threatened, which led her to make a remarkable statement to an interviewer a few years before her death: “I used to tell my dad that I was disappointed I had not been taken to the concentration camps. I knew I could have helped others, and that desire to help never abandoned me.”

Lisetta Carmi: Identities is at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London, until December 17