A smiling boy poses by his bicycle. Hand on hip, justifiably proud that he made it himself out of bits and pieces he had found or bought with his pocket money. A Union Flag flutters from the handlebars.

Yet within a few years, that flag had become a symbol of colonial oppression as the boy, and many like him, found themselves caught up in a climate of racism and violence.

The photograph, Boy with Flag, Winford, in Handsworth Park (1970), was taken by Jamaican-born Vanley Burke as part of a series about the West Indian community in the Birmingham suburb.

In 1977, not many years later, Burke was photographing protest marches in Handsworth. Instead of a flag, protesters carried a banner proclaiming: “Afrika (sic) Liberation Day… we are our own liberators”. In a visual echo of the boy with flag photograph, the march was led by outriders on bicycles as ramshackle as young Winford’s.

Burke’s photographs are featured in the Life Between Islands exhibition at Tate Britain. On display are films, photographs, paintings and sculpture by 40 artists of Caribbean heritage.

Covering the 1950s until now, the exhibition includes long-established names such as Ronald Moody and Frank Bowling and contemporary artists such as Hew Locke, Steve McQueen and Isaac Julien. Some of the most telling work comes from photographers and painters active in the 1970s and 1980s, less well known but are every bit as powerful and perceptive.

The displays explore the past 70 years of British history from the perspective of those who feel disconnected from their heritage and those, such as members of the Windrush generation, who faced discrimination and racism.

It all feels very timely. In recent weeks it has been revealed that only 5% of the 15,000 Windrush victims had received compensation four years after the scandal emerged.

The exhibition is characterised by images of anger and bitterness, as well as longing and nostalgia, with only a few featuring the calypso singing, carnival dancing, joie de vivre usually associated with the Caribbean, cliches perhaps created by the white onlooker (and local tourist boards).

The works are shown more or less chronologically and divided into several cultural movements, starting with the generation who came to Britain in the 1940s and 1950s, and whose work conveyed a yearning for their places of birth and a desire to preserve their own identity and that of the islands. Aubrey Williams brought his mix of American abstract expressionism and the imagery of the indigenous people of his home country, Guyana, to Sun and Earth II (1963) and Tribal Mark II (1961), while fellow Guyanese Frank Bowling articulated his love for home using tropical colours. In Kaieteurtoo (1975), he captured the power of the Kaieteur Falls by setting up his canvas at a 45-degree angle, pouring paint from the top and letting the colours flow down the canvas.

There is an urge to recover lost heritages in the works of the Caribbean Artists Movement, which developed in the 1960s. Paul Dash painted jiving bodies in Dance at Reading Town Hall in a moody nightclub-blue, and his dense style, which many have compared to Walter Sickert, is on display in Talking Music, in which two guitarists tune up while friends look on. They all seem to be having fun – as do the characters chronicled by photographer Charlie Phillips, including an old dear kissing a faintly amused Black man in Outside the Piss House Pub, Portobello Road (1969).

These are scenes far removed from the placard-bearing protesters who were to become familiar sights in the late 1970s and the 1980s. By then, the angry echoes of the Black Power and civil rights movements in the United States were influencing British counterparts. Horace Ové photographed Michael X, leader of the Black Power Movement and his entourage, striding out of the shadows of Paddington station on their way to a rally, while another image shows Darcus Howe rallying the crowd at the trial of the Mangrove 9, a group of Notting Hill West Indians unlawfully accused of inciting a riot by corrupt police officer.

One of the most potent of images is Black Panther School Bags (1970) by Neil Kenlock. It shows four girls looking slightly self-conscious as they clutch their satchels, one inscribed with the word “Black”, the others with the outline of a gun and a raised clenched fist.

In the 1980s, riots broke out across the country from Brixton in London to

Handsworth in Birmingham and Toxteth in Liverpool. Hundreds were arrested, millions of pounds of damage was caused and in the Broadwater Farm Estate in north London, two died – a West Indian woman named Cynthia Jarrett, and PC Keith Blakelock.

The terrible events are reflected in the ironically titled, The Sky at Night (1985) by Tam Joseph – the vast canvas shows the forbidding bulk of the Broadwater Estate at night, the darkness relieved only by a handful of lighted rooms. A fire blazes in the foreground, the shadowy figures of protesters flicker on one side of the flames, police are massed on the other.

It is a scene of menace and of despair.

As anger spread across the country, photographers such as Pogus Caesar and Vron Ware were on hand to record the confrontations between protesters and police but some of the most dramatic images are by painters.

Eddie Chambers has a union jack-cum-swastika disintegrating into pathetic shreds in Destruction of the National Front (1979-80) and Tam Joseph, inspired by his Dominican roots, shows an exuberant masked performer penned in by a circle of riot police and threatened by a snarling dog in The Spirit of the Carnival (1982).

Perhaps the most powerful is Denzil Forrester’s Death Walk (1983), one of

several paintings created in tribute to his friend Winston Rose, who died in

police custody in 1981.

Rose is shown lying face down, arms outstretched on top of a coffin. Forrester was told that after he had died, the police rested their boots on the body when they were in the van.

That ugliness of the times is also captured in Isaac Julien’s video Territories (1984), with its collision of conflict between carnival revellers and the police, made ever more disturbing by its turbulent rush of scenes, the noise of sirens and shouts, grimacing faces gripped with fear. Anger, frustration, disillusion – these are the emotions portrayed in so many of the works, but there is also nostalgia and longing.

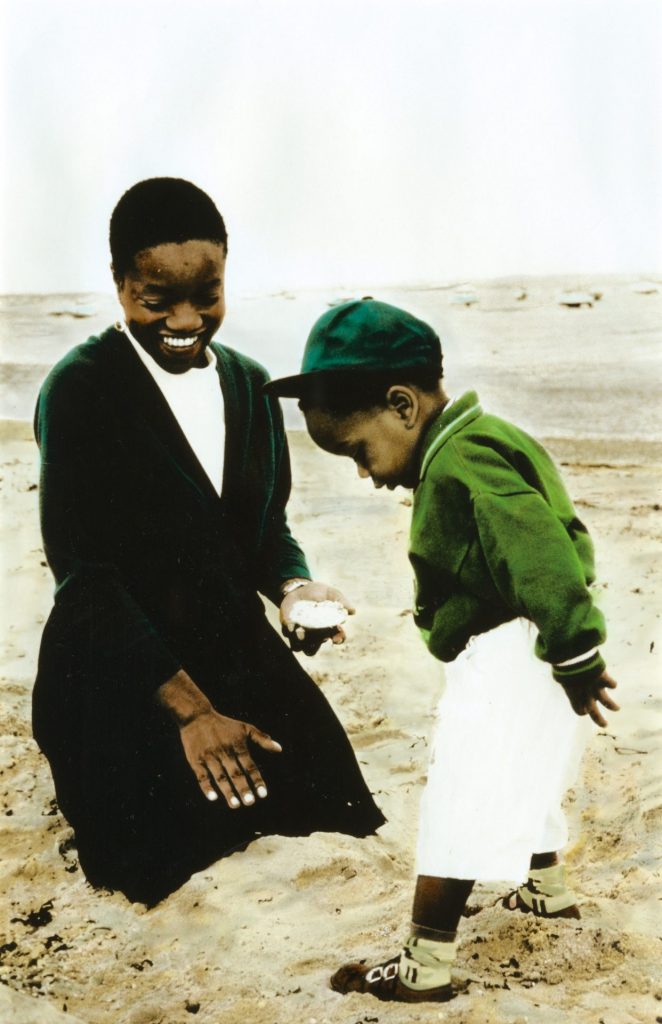

Ingrid Pollard, who left Guyana when she was four, frames holiday snaps from family albums to express her feeling of dislocation in Oceans Apart (1989): a mother and son play on a sunny West Indian beach, a boy rides a pony, children lark around while cold Atlantic waves crash against the shore. She adds to the sense of loss with echoes from her father’s letters: “My dear daughter, now we are Oceans apart… oceans apart… oceans apart.”

There is something of that longing in Isaac Julien’s video Paradise Omeros (2002), which tries to make sense of two separate but connected cultures: that of 1960s England and contemporary Saint Lucia, the home of his parents. On the one hand, the sunny beaches and exuberant rainforests of the island, while on the other, a rain-swept housing estate in London. Caught between those worlds, a young man tries to puzzle out where he belongs.

For many, the draw of “paradise” has proved too strong to resist. Peter Doig, the British artist who settled in Trinidad in 2002, uses broad brushstrokes to conjure up the heat and light of the island with The Music of the Future (2002-7) and the eerie Moruga (2002-8), with its canoe venturing into a stormy night with a St George’s flag hoisted high, and what looks like a crusader brandishing a sword. And if the exhibition is short on calypso, Paragon (2006) at least celebrates cricket, that most West Indian of sports.

But paradise can be elusive. Hurvin Anderson, who was born in Birmingham to Jamaican parents, and was taught by Peter Doig, also returned to paint idyllic scenes such as Maracas III (2004) and the deceptive Hawksbill Bay (2020). Deceptive because what seems a scene of tumbling tropical trees and foliage is hiding neglected developments and rundown hotels.

For Anderson, the beautiful Jamaica remembered by his parents was also one blighted by economic hardship and he admits to mixed feelings about the “grandeur and loss, of a garden of Eden, a lost city and the pain of nostalgia.”

Perhaps we return to a kind of normality – free from pain, free from protest – in the last painting of the exhibition. Nigerian Njideka Akunyili Crosby portrays a rather awkward family gathering in Remain, Thriving (2018).

There are reminders of generations past – a photograph of a man in military uniform, a father, perhaps, family snaps on the mantelpiece, dated furniture, a big gramophone, and busy wallpaper, which has references to people and places of their Brixton community.

Back to normal? The TV news is on, unwatched. A Black woman is being interviewed. The headline reads: Developing story: Windrush scandal.

Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s-Now, Tate Britain until April 3.